Contents

Page List

Guide

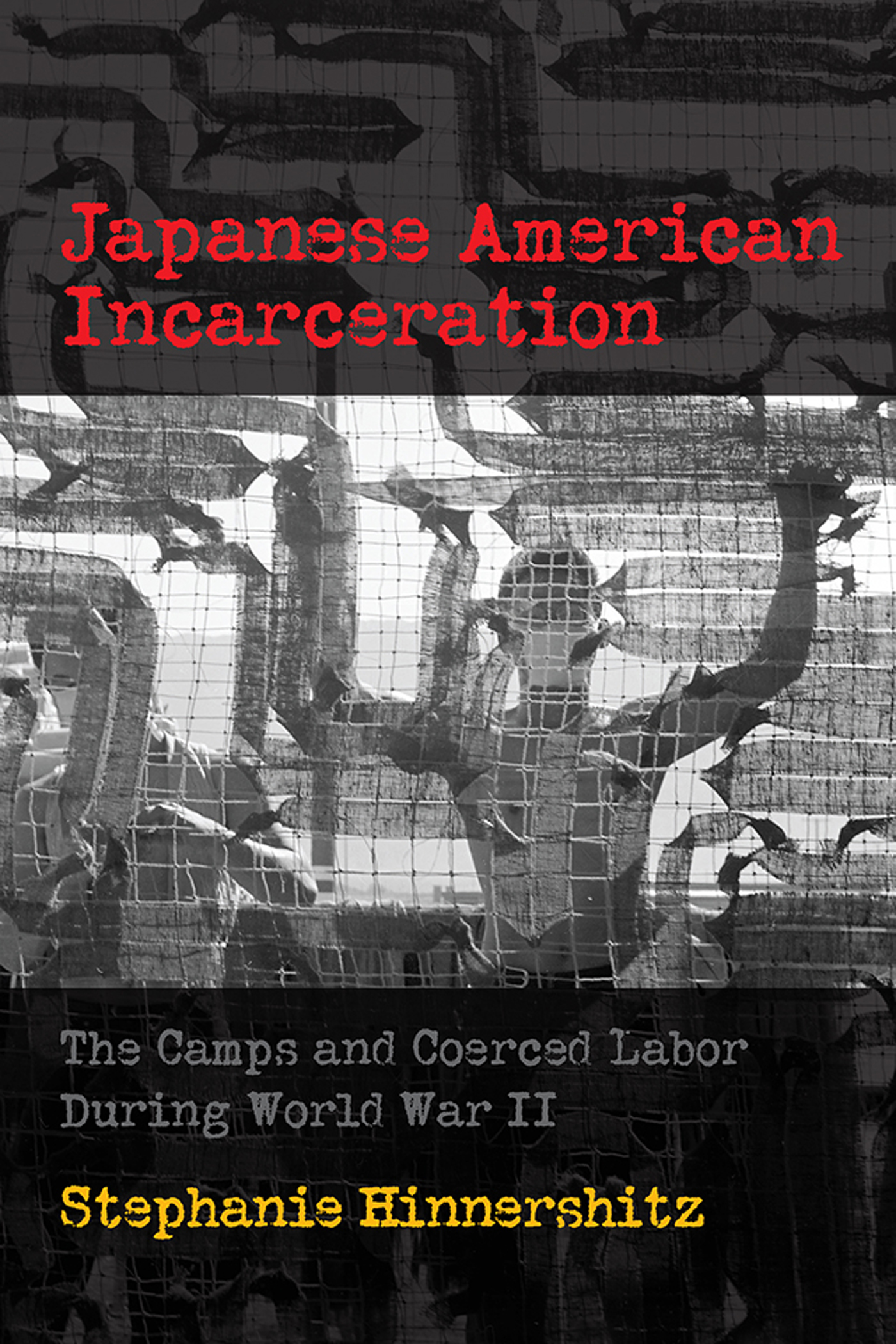

Japanese American Incarceration

POLITICS AND CULTURE IN MODERN AMERICA

Series Editors: Keisha N. Blain, Margot Canaday, Matthew Lassiter, Stephen Pitti, Thomas J. Sugrue

Volumes in the series narrate and analyze political and social change in the broadest dimensions from 1865 to the present, including ideas about the ways people have sought and wielded power in the public sphere and the language and institutions of politics at all levelslocal, national, and transnational. The series is motivated by a desire to reverse the fragmentation of modern U.S. history and to encourage synthetic perspectives on social movements and the state, on gender, race, and labor, and on intellectual history and popular culture.

Japanese American Incarceration

The Camps and Coerced Labor During World War II

Stephanie Hinnershitz

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2021 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-8122-5336-8

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

In the summer of 1942, George Yamauchi worked nine hours a day, six days a week making camouflage netting for the United States Army. Yamauchi was one of twelve hundred workers at his factory who wove together long strips of nylon to make these crucial military supplies, using large wire fences to drape the massive nets as they grew with each woven row, arduous work in the sun. Rather than a large, sprawling plant like the ones where Rosie the Riveters or men who were not able to serve in the armed forces worked making munitions, plane parts, and other industrial products, this factory was located in the open, hot air of southern Californias Santa Anita assembly center. As the sun set, Yamauchis shadow cast over the netting, signaling that it was soon time to quit work for the day. He joined others in the mess hall for their evening supper, frequently hot dogs, baked beans, and a dessert of canned fruit or perhaps prunes, maybe a green salad.

Yamauchi was a Nisei, an American-born citizen of Japanese descent, and a skilled weaver. For his daily work on the camouflage nets, he made fifty-three cents a day, or approximately sixteen dollars a month. With these wages, he bought clothing, snacks, and other sundries at the center canteenfor prices that seemed quite a bit more exorbitant than what he remembered as a free man in California. At the end of the day and after his evening meal, Yamauchi challenged some of the other incarcerees to a game of basketball or read the latest copy of the Santa Anita Pacemaker, the censored newspaper published by his fellow detainees at the center. But whatever he did to pass the time in the evening, every day ended the same way: Yamauchi removed his clothes, climbed into his cot with a straw mattress in his barracks, and drifted off to sleep, possibly thinking about the life he had before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Yamauchi, like other Nisei, Issei (first-generation Japanese migrants), and Kibei (Japanese American citizens educated in Japan), were detained in assembly centers along the West Coast during the late spring and early summer of 1942 as they awaited reassignment to one of ten internment camps from California to Arkansas. And, like the other imprisoned Japanese Americans, the administration at Santa Anita expected Yamauchi to work.

Labor. Labor as a necessity for the American war economy. Labor as a means of preventing idleness and moral decay in the incarceration centers. Labor as a redemptive act necessary for the reclamation of American citizenship. Conceptions of and concerns about labor shaped the incarceration of approximately 115,000 to 120,000 Japanese Americans during World War II in ways great and small. The evidence for this is in plain sight, spread across documents in personal, state, and federal archives and in photos featured in museums and online exhibits.

In observance of the seventy-fifth anniversary of Franklin Delano Roosevelts decision to sign Executive Order 9066 in February 1942 designating areas along the West Coast as military zones, the FDR Presidential Library in Hyde Park, New York, displayed a special exhibit in 2017 titled Images of Internment. The temporary exhibit featured photos by Dorothea Lange and Ansel Adams of wrongfully imprisoned Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their homes by the army. Many of the images depicted incarcerated Japanese Americans at workyoung and old, first and second generationfarming, sewing, completing clerical tasks, manufacturing war materials, and constructing their own barracks. Individual portraits of imprisoned Japanese Americans identify them by name first, occupation within the camps second.

The extraction of Japanese American labor looms just as large in the records of the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the Wartime Civil Control Administration (WCCA), and various divisions of the army in charge of planning and implementing EO 9066 and subsequent imprisonment of Japanese Americans. In memos, letters, and telephone conversations, the architects and administrators of incarceration expressed their fears that labor strikes in the camps would undermine order and that Japan would view the work performed by Japanese Americans as forced, using this to justify atrocities against American prisoners of war. Pulling these sources together reveals that the extraction of labor was a crucial component of the policy, planning, and implementation of the mass incarceration of Japanese Americans.

Although the photos of laboring Japanese Americans are no longer on the walls of the special exhibit hall at Hyde Park, gazing on them in collections held at the Library of Congress or the National Archives and Records Administration highlights the fact that labor was central to the experience of imprisoned Japanese Americans. Prisoners performed the same work on camouflage netting as Yamauchi did in the Poston and Manzanar prison camps during the summer and fall of 1942. In the spring of 1943, thousands of single men and families left the camps to work for private farmers in the Mountain States. These men and women were freed for work but were under threat of recall by the WRA either for violating myriad public proclamations limiting their activities or if their labor was required in the prison camps. Limitations on Japanese American freedom rendered their labor outside the camps as more of a work release program, and indeed the public often referred to these workers as parolees on trial leave. Elsewhere, Japanese Americans built irrigation ditches meant to render tracts of the dry and dusty Arizona desert fit for Native American or GI Billeligible veteran settlement. Although Japanese Americans typically received between twelve and eighteen dollars a month and signed contracts with the WRA or private employers, labor disputes served as a catalyst for riots and strikes that revealed deep resentment over poor working conditions in and out of the prisons. Disillusionment and dissatisfaction over unpaid wages as well as exploitative and coercive conditions were central to the Japanese American experience of incarceration.