Titles in the Series

The Assassination of John F. Kennedy, 1963

Blitzkrieg! Hitlers Lightning War

Breaking the Sound Barrier: The Story of Chuck Yeager

Building the Panama Canal

The Civil Rights Movement

The Creation of Israel

The Cuban Missile Crisis: The Cold War Goes Hot

The Dawn of Aviation:

The Story of the Wright Brothers

Disaster in the Indian Ocean: Tsunami, 2004

Exploring the North Pole:

The Story of Robert Edwin Peary and Matthew Henson

The Fall of the Berlin Wall

The Fall of the Soviet Union

Hurricane Katrina and

The Devastation of New Orleans, 2005

The McCarthy Era

An Overview of the Korean War

An Overview of the Persian Gulf War, 1990

An Overview of World War I

The Russian Revolution, 1917

The Scopes Monkey Trial

The Sinking of the Titanic

The Story of September 11, 2001

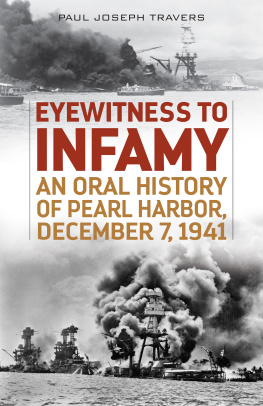

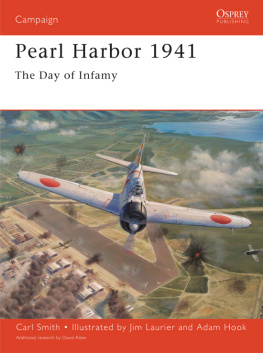

The Story of the Attack on Pearl Harbor

The Story of the Great Depression

The Story of the Holocaust

Top Secret: The Story of the Manhattan Project

The Watergate Scandal

The Vietnam War

Copyright 2006 by Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Printing 3 4 5 6 7 8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Whiting, Jim, 1943

The story of the attack on Pearl Harbor / by Jim Whiting.

p. cm. (Monumental milestones)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 1-58415-397-0 (library bound)

1. World War, 19391945Pacific AreaJuvenile literature. 2. Pearl Harbor (Hawaii), Attack on, 1941Juvenile literature. 3. World War, 19391945United StatesJuvenile literature. 4. World War, 19391945JapanJuvenile literature. I. Title. II. Series.

D767.W473 2005

940.54'26dc22

2004030309

ISBN-13: 9781584153979

eISBN-13: 9781545749425

ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jim Whiting has been a remarkably versatile and accomplished journalist, writer, editor and photographer for more than 30 years. A voracious reader since early childhood, Mr. Whiting has written and edited about 200 non-fiction childrens books. His subjects range from authors to zoologists and include contemporary pop icons and classical musicians, saints and scientists, emperors and explorers. Representative titles include The Life and Times of Franz Liszt, The Life and Times of Julius Caesar, Charles Schulz, The Cuban Missile Crisis: The Cold War Goes Hot, and Juan Ponce de Leon.

Other career highlights are a lengthy stint publishing Northwest Runner, the first piece of original fiction to appear in Runners World magazine, hundreds of descriptions and venue photographs for America Online, e-commerce product writing, sports editor for the Bainbridge Island Review, light verse in a number of magazines, and acting as the official photographer for the Antarctica Marathon.

He lives in Washington state with his wife and two teenage sons.

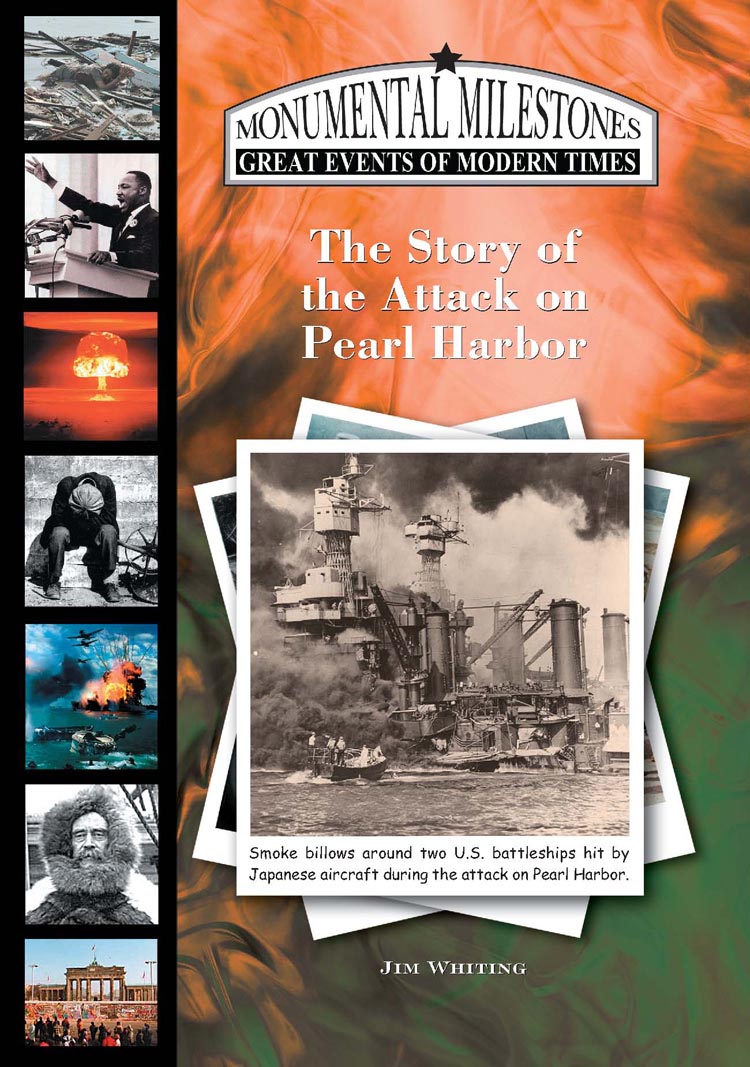

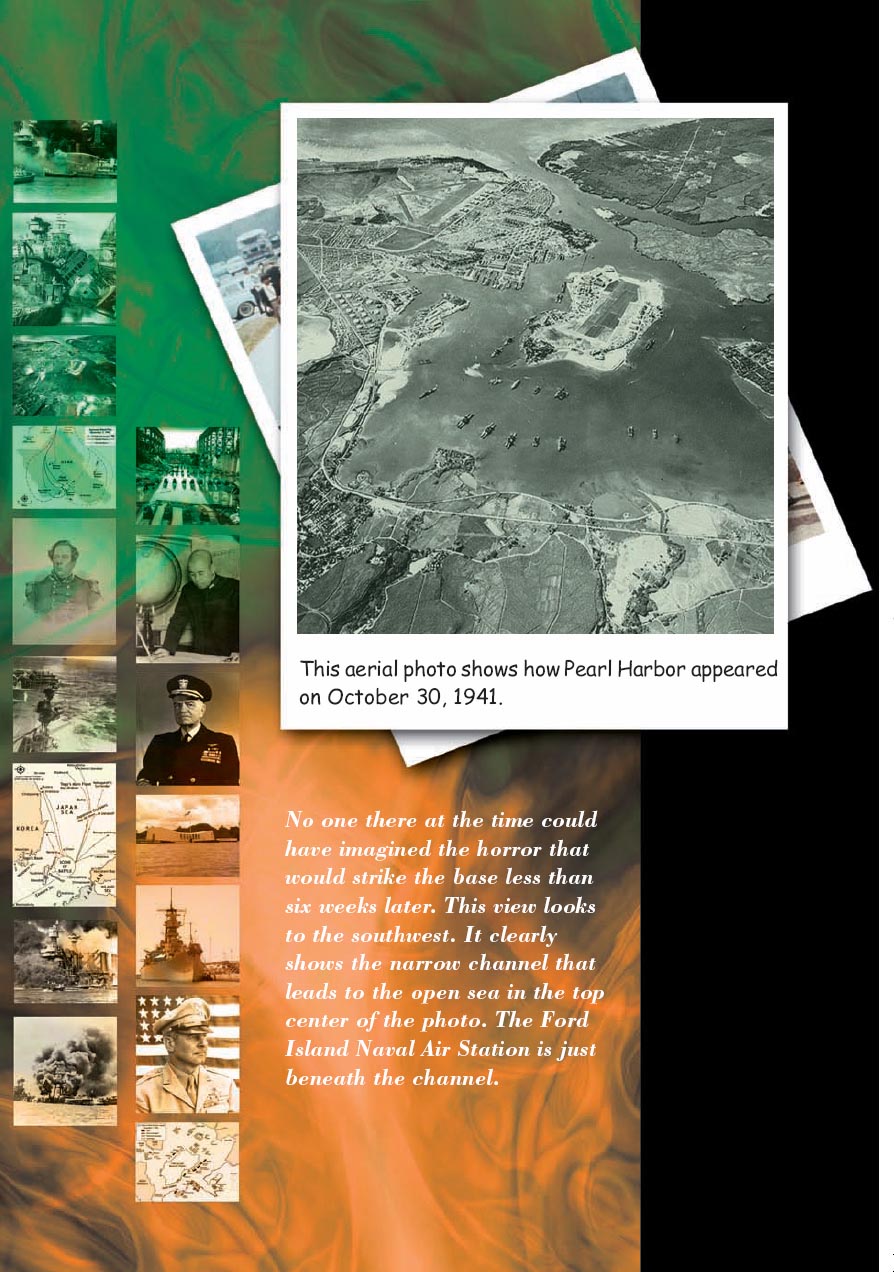

PHOTO CREDITS: Cover, pp. 1, 3, 6, 20, 22, 26, 28, 32, 37Naval Historical Center; pp. 10, 34Sharon Beck; p. 12Library of Congress.

PUBLISHERS NOTE: This story is based on the authors extensive research, which he believes to be accurate. Documentation of such research is contained on page 47.

PLB4 / PLB2,4

Contents

The Story of the Attack on Pearl Harbor

Jim Whiting

*For Your Information

CHAPTER

A Morning of Missed Warnings

Ensign R. C. McCloy carefully scanned the dark waters just outside of Pearl Harbor with his binoculars. Pearl Harbor was the most important U.S. military installation on the Hawaiian island of Oahu (oh-WAH-hoo). It was about 0340 (3:40 A.M.) on December 7, 1941. McCloy was standing on the bridge of his ship, the minesweeper USS Condor. The vessel was on a routine patrol.

McCloy, like nearly every serviceman stationed at Pearl Harbor and several other military bases on Oahu, knew there was a good chance that his country would soon be at war with Japan. Like nearly every other serviceman, he couldnt imagine that the beginning of the war would involve him personally. Japan was thousands of miles away from Hawaii.

Military commanders were more concerned about the loyalty of the people of Japanese descent who lived in Hawaii than they were about Japanese nationals. When war broke out, they were afraid that some of them might try to commit acts of sabotage. To reduce that possibility, hundreds of aircraft on Oahus airfields were out in the open and packed closely together. That made them easier to guard.

McCloyand nearly every other servicemanwas wrong. About 300 miles north of him, hundreds of mechanics were swarming over more than 350 warplanes on six Japanese aircraft carriers. The carriers and their escorting warships had steamed undetected for more than a week since leaving Japan. In just over two hours, the planes would start taking off. Their destination was Oahu.

McCloy stiffened. Not far away he saw the unmistakable shape of a periscope. McCloy knew it wasnt an American submarine. They werent allowed to be submerged in that area. Quickly he sent a message to the USS Ward, a destroyer patrolling nearby. The Ward was equipped for locating subs. Though it spent an hour searching, the Ward could not detect anything. Neither vessel sent a message ashore about what they were doing.

At about 0630, the supply ship USS Antares was preparing to enter the channel leading into Pearl Harbor. Lookouts aboard Ward and a Catalina patrol plane sighted a curious object just behind Antares and moving at the same speed. Soon they realized that it was a tiny, partially surfaced submarine. It was obviously trying to sneak into Pearl Harbor. The plane dropped smoke pots to mark the location. At 0645, Wards gunners opened fire. A shell hit the submarine and it began to sink. For good measure, Ward dropped several depth charges.

At 0654, Ward sent a short message in code to the shore station: We have attacked, fired on, depth-bombed, and sunk submarine operating in defensive sea area. The man who received the message took more than fifteen minutes to decode it, then passed it along to the officer on duty. The officer was alarmed. When he notified his superiors, they werent. There had been a number of false alarms near Pearl Harbor in the past few weeks. Many phone calls went back and forth. In the confusion, some vital information was lost. One was that Ward had actually seen an enemy submarine. Another was that the ship had shot at the target.

Besides, the officers all knew that heavy concentrations of Japanese warships and troop transports had been observed off the coast of Siam (modern-day Thailand) and other locations in southern Asia thousands of miles away. It seemed obvious that the war would start there. None of the officers seemed especially concerned about Wards message. There would be plenty of time to verify the report.

Next page