Campaign 62

Pearl Harbor 1941

The Day of Infamy

Carl Smith Illustrated by Jim Laurier and Adam Hook

Additional research by David Aiken

CONTENTS

US Commanders Japanese Commanders

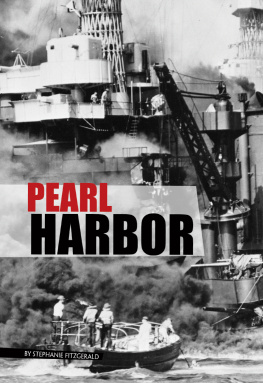

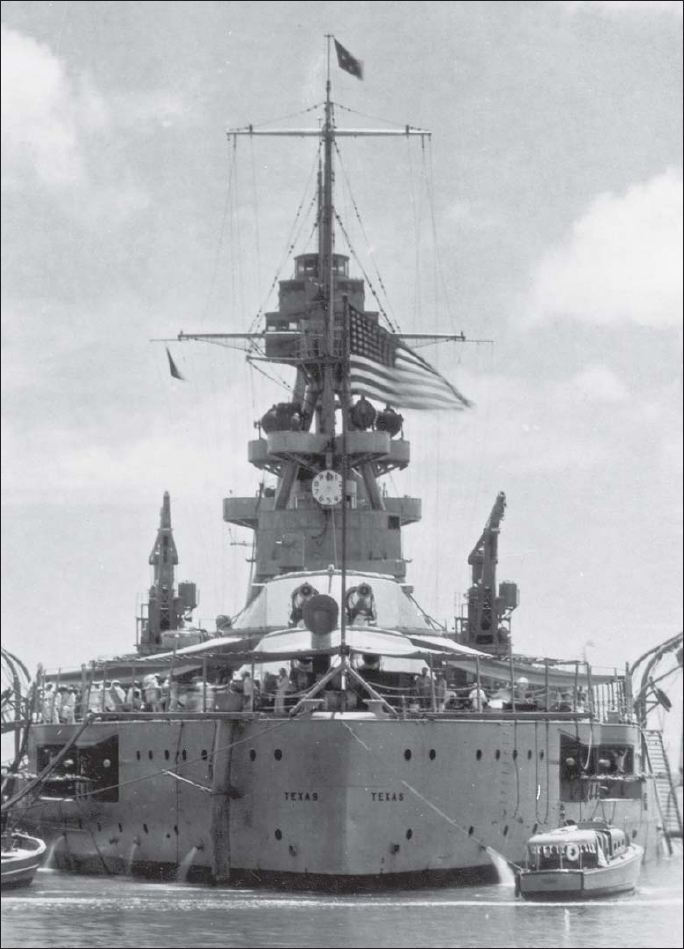

Pearl was a natural harbor that had been used for over 100 years. An early visitor was the battleship USS Texas, shown here with sun awnings in place over the foredeck. In 1940, the Pacific Fleet transferred from California, worrying Japanese military strategists, who saw it as a threat to Japanese security. Texas was serving in the Atlantic at the time of the Japanese attack.

INTRODUCTION

B elow, thick fluffy clouds blanketed the blue sky. Shoving the stick forward, Lt. Mitsuo Matsuzaki dropped his Nakajima B5N2 Type 97 (Kate American forces used call names for quick identification) AI-301 beneath them into more blue sky, the horizon broken by the low verdant land mass he was approaching. His observer, Cmdr Mitsuo Fuchida, the mission commander, was watchful. Hawaii looked green and oddly peaceful. He scanned the horizon. It looked too good to be true; other than his fliers, no planes were visible. Fuchida remembered, years later, how peaceful it had appeared.

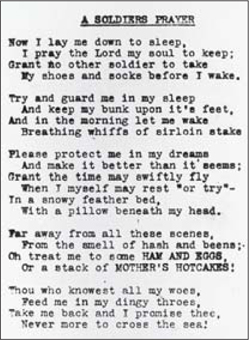

Bored servicemen in Hawaii were always vocal about living conditions or carping about food and barracks life. A Soldiers Prayer was circulated at Hawaiian military installations just prior to the attack. After December 7, boredom was forgotten.

It was 0730 hrs Hawaii time; the date, December 7, 1941. Fuchidas destination was the home of the US Pacific Fleet Pearl Harbor. The fleet and three aircraft carriers berthed there were the key targets. A statement notifying the US that war had been declared had been scheduled for delivery to Washington an hour earlier. This air strike would be the first act of war between Imperial Japan and the United States.

All the planning, endless exercises, and practice runs would determine the success of this attack. Some military minds thought it would cripple the US fleet; others hoped it might scare the Americans into appeasement; but most felt it would pull Japan into a war with the United States. If war was to be the outcome, some had said, then let it begin here, because Japans best hope for winning a conflict with the Western giant was to strike first and cripple the US Navy. Japanese forces could then act with a free hand in the following months and further expand their conquests. For Cmdr Fuchida much of this was immaterial, for he was a career officer with a mission: bomb Pearl Harbor.

Political background

The Hawaiian Islands lie in the middle of the Pacific, west-south-west of the United States, the first real landfall west of the mainland, positioned at 150170 longitude (just east of the International Date Line) and between 18 and 29 north of the equator. Kauai, Niihau, Oahu, Molokai, Maui, Kahoolawe, Lanai, and Hawaii form the major islands in the chain, originally called the Sandwich Islands. The northernmost edge is at roughly the same latitude as Los Angeles, giving the Hawaiian Islands a uniform, mild annual temperature of 75 Fahrenheit and a tropical climate, with cooling ocean breezes, rainforests, and dramatic stretches of beach at the foot of majestic mountains and volcanoes. These islands, between Japan and the United States, are a perfect military base, first for naval attack and then for air power.

Hawaii had been discovered by Europeans in the mid-1700s. First ruled by a monarchy, in 1900 it became a US territory, but it was not made a state until 1959. The land is fertile and the beaches, when properly cultivated, yield immense crops of American, Japanese and international tourists. By the 1930s, the population of Hawaii was mostly American and Asian, with its indigenous peoples waning.

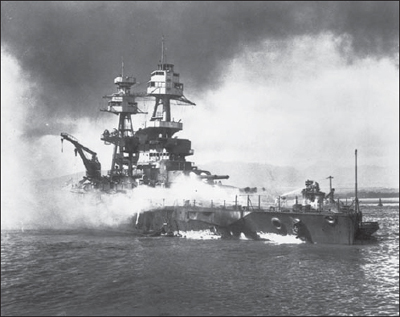

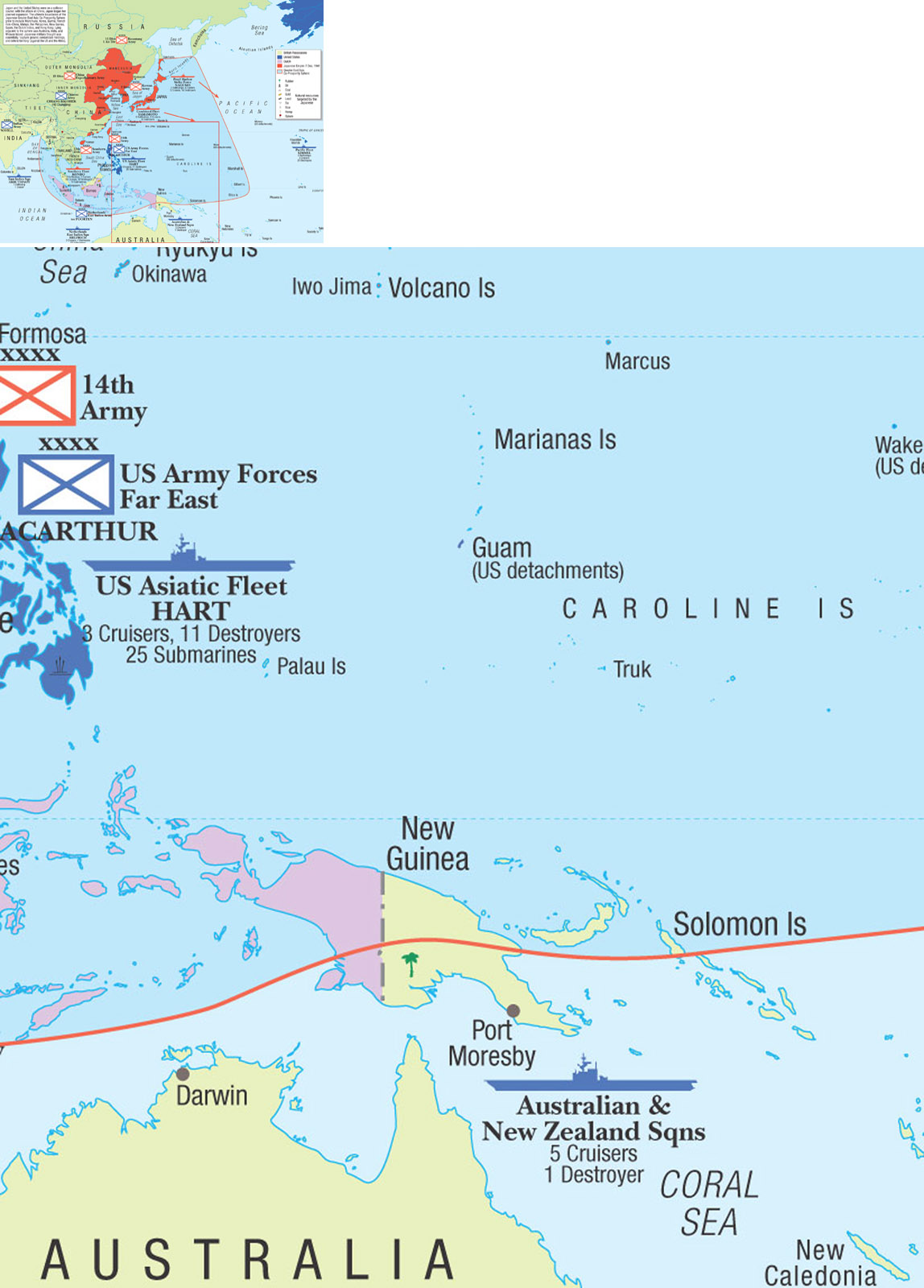

Pearl Harbor was the first stopping point in Pacific waters. Because air power attack was theoretical, Pearls fortifications relied heavily on coastal guns in heavy positions to defend against naval bombardment.

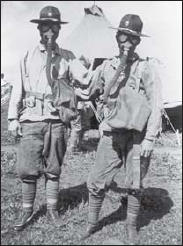

Despite the war in Europe, in 1941 the US Army was not ready to fight a modern war. Although in 1936-issue field gear, these soldiers on maneuvers would look at home in French trenches a quarter of a century earlier. Note the cloth puttees, campaign hats and gas masks reminiscent of World War I.

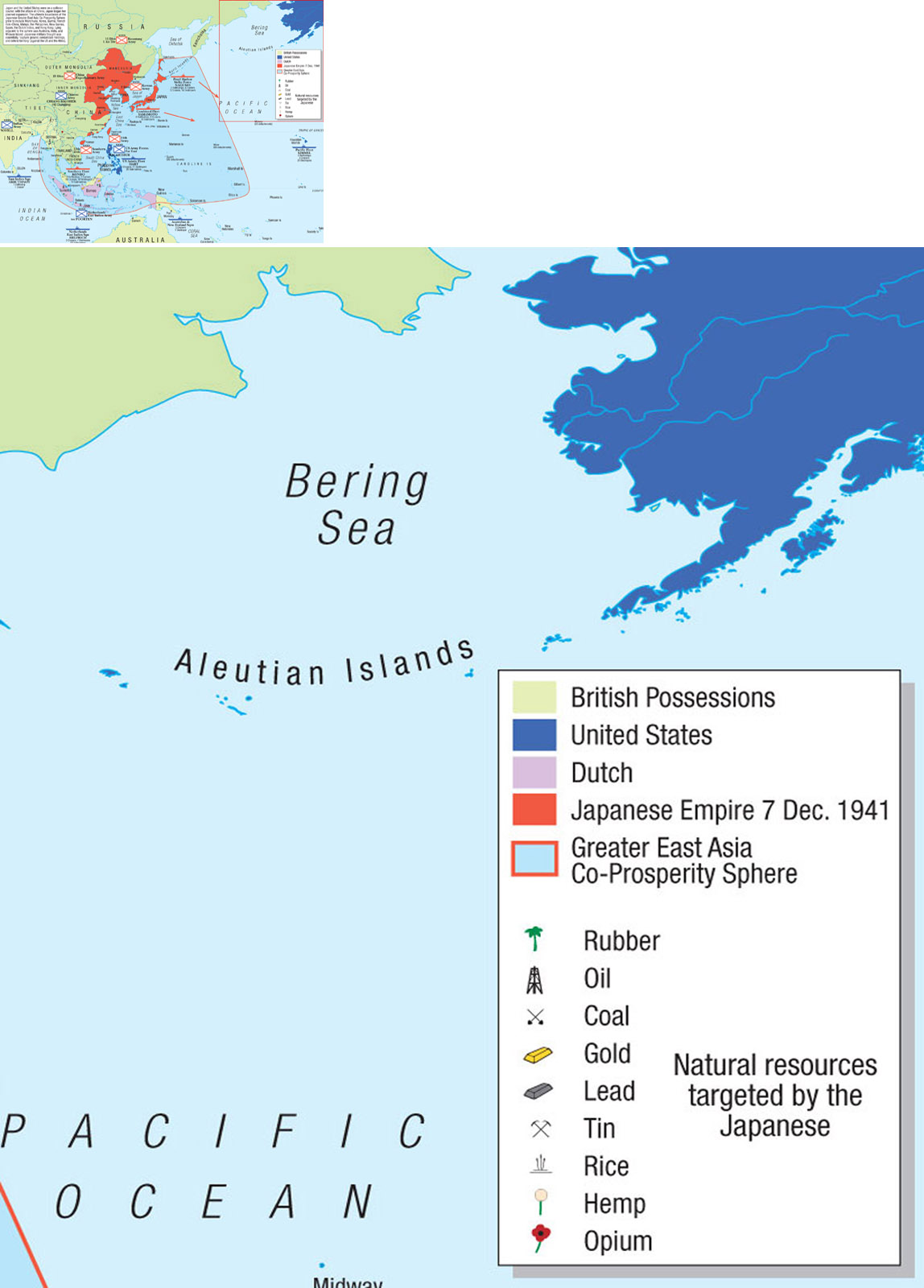

Japan noted the islands as a potential threat to expansion. Since before the Russo-Japanese War, Japan had been full-steam-ahead modernizing, manufacturing and upgrading its military. With these changes came increased demand for natural resources (steel, oil, gas, raw materials and minerals) and their eyes turned east to China, Indochina, and the islands of the Pacific. Although Russia had traditionally been viewed as the major threat to Japanese expansion and Asian influence, the American and European presence in Asia became increasingly important.

The Japanese felt European powers were limiting growth of their empire: as Japan expanded, European resistance coalesced which in turn supported Japanese fears of intervention and limitation. The US Congress placed restrictions on business with Japan, and then the majority of the US Pacific Fleet made Pearl Harbor its home. Real or imagined, the US fleet posed a threat, and Japan viewed Hawaii with special interest.

The situation worsened as Japan felt strangled and besieged. When war erupted in Europe, and the United States did not intervene as France and Britain became embroiled in conflict with Germany and Italy, Japan noticed. America, it seemed, wanted neutrality: perhaps they would overlook expansions in Asia.

Europeans might have to fight wars on two fronts, but obviously Europe would be their primary theater and the Pacific would occupy a back seat. The US Pacific Fleet was a deterrent. Japanese and American spheres of influence grew, stretching thinner, threatening to burst. Japan and the United States moved on a collision course: the former needed to grow, the latter wanted to maintain the status quo. Relations worsened, and nationalistic distrust blossomed.

Next page