TORA! TORA! TORA!

Pearl Harbor 1941

MARK E. STILLE

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

As early as 1914 the Japanese and Americans were thinking of each other as possible future enemies. This potential came more sharply into focus when in the 1930s Japan openly embarked on a path of aggression. Beginning in 1931, Japanese actions clearly indicated that their goal was to dominate East Asia.

The central issue between Japan and the United States in the period leading up to war was Japanese aggression in China. Not only did this aggression threaten Chinas integrity, but it jeopardized American trade interests. Despite the fact that it was not one of its primary national security interests, the United States remained committed to Chinese sovereignty. As the Japanese pressed deeper into China and prosecuted the war with increasing brutality, the Americans began to translate Japanese dependence on resources from the United States into economic pressure. Throughout 1940 the US ratcheted up the economic pressure on Japan in an attempt to curb Japans imperial ambitions without war. In July 1941, in an attempt to forestall a Japanese advance into French Indochina, the United States froze all Japanese assets in the United States and slapped Japan with a complete trade embargo including oil. In an era when the US supplied Japan with 75 to 80 percent of its imported oil (and Japan imported 90 percent of all oil that it consumed), this was a declaration of total economic war. Making matters worse for Japan, the governments of Great Britain and the Netherlands followed the lead of the United States.

The hard line pursued by the US demanded a Japanese response. Doing nothing was not an option since within 18 to 24 months Japans oil supplies would be exhausted, which would reduce it to impotence. Essentially, Japan faced one of two alternatives. It could submit to the United States or seize the initiative and use force to extract itself from this dilemma. The price for submission set by the Americans was too high to contemplate by Japans military rulers. These demands included that Japan abandon its gains in Indochina, China, and, it was even feared, in Manchuria. Not only was this impossible from the standpoint of national pride, but to do so would place Japan in a permanent position of strategic vulnerability to the United States.

There was little debate within the Japanese leadership that the only alternative was to fight. This course of action offered a way out of the American economic stranglehold since seizure of the lightly defended oil resources in the Dutch East Indies, together with the resources of the British possessions in Asia, could negate the effects of the American embargo. The price of this solution was war with Great Britain and the Netherlands, and, much more importantly, probably with the United States as well. In the minds of the Japanese leadership, all three western powers were linked strategically. Since the Netherlands was already occupied by the Germans, and Great Britain was fighting for its very survival, only the United States possessed the military means to threaten Japans potential march south.

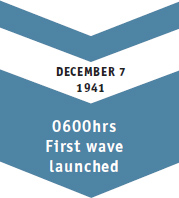

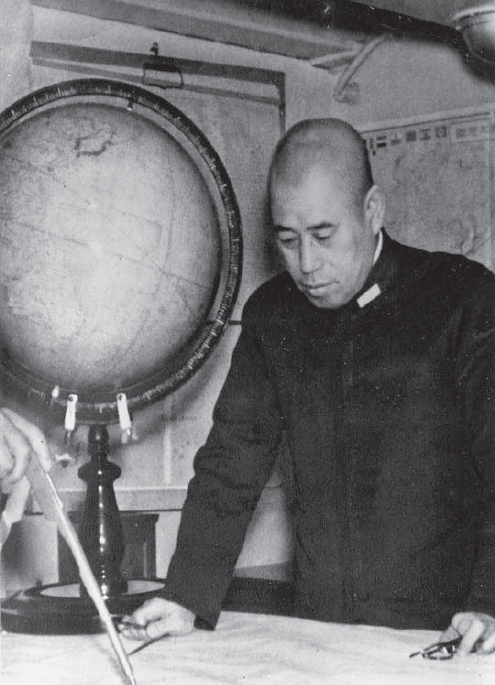

The driving force behind the Pearl Harbor attack was the commander of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku. Against almost universal skepticism he achieved his goal of opening the war against the United States with a daring attack against the heart of American naval power. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

With this strategic setting, the Japanese began to look at the best strategy for engaging in a war with the strongest nation and the largest empire on the planet while still fighting a war in China that defied military or political solution. On top of this, Japan still harbored designs of striking the Soviet Union in the Far East. The key for Japans strategic planners was to gain the six months required to successfully conquer the resource areas in the south to give it the economic base to prosecute a war against all its current and potential enemies.

As dubious as this strategic calculus seemed to any outside observers and even to a few clear-headed Japanese thinkers, Japan now elevated its level of strategic folly by initiating a war against the United States with no clear notion of how such a war might be concluded. This was even more startling when it is remembered that the United States possessed a wide advantage over Japan in every measure of national power. Since Japans notion of victory over the United States revolved around a negotiated settlement on terms allowing Japan to keep its gains in Asia, the way it began such a war mattered to its outcome. Into this quandary stepped the Imperial Navy, which had been planning a war against its United States counterpart for over 20 years.

To fight a naval war against the United States, the Imperial Navy had been built for a decisive battle near Japanese home waters. With war predicated upon taking and holding key resources areas in Southeast Asia, the Japanese notion of a decisive naval battle was forced to change to reflect the requirement to defend Japans new gains by mounting a forward defense in the Central and Western Pacific. Now, as war with the United States appeared increasingly certain, Japanese naval strategy was transformed again under the guidance of the commander of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku. He did not share the almost mythic belief in the decisive battle concept. Yamamotos key to victory in a war against the United States was a negotiated settlement that would be prompted by an opening blow against the American fleet followed by a quick seizure of the southern resource areas. Under Yamamoto, the Imperial Fleet would not be content to lie in wait for the US Navy as it sailed across the Pacific, but would instead open the war with a crippling blow against the United States Pacific Fleet. So devastating was the blow he was planning that it would shatter US morale and bring the Americans to the negotiating table. This thinking provided the strategic framework for the attack on Pearl Harbor.

ORIGINS

Throughout 1941, as tension between Japan and the United States mounted, the Japanese pursued a duel track of diplomatic engagement in parallel with preparations for war should negotiations fail. On February 12, 1941, Japans new ambassador to the United States, Nomura Kichisaburo, presented his credentials to the American Secretary of State, Cordell Hull. Nomura believed that peace could be preserved by negotiations, and remained ignorant throughout the process that his nation was increasingly intent on war while marginalizing diplomacy. On April 16 Hull presented Nomura with the American governments basis for negotiations. Misunderstanding marked the negotiations from the start as demonstrated by the Japanese response the following month. The Japanese consistently overestimated the willingness of the United States to make concessions. The Americans were negotiating on principle and never detected any movement by the Japanese. Accordingly, diplomacy never gained any traction in the run-up to war. Essentially, Nomuras mission could succeed only if the Americans agreed to Japans terms.