INTRODUCTION

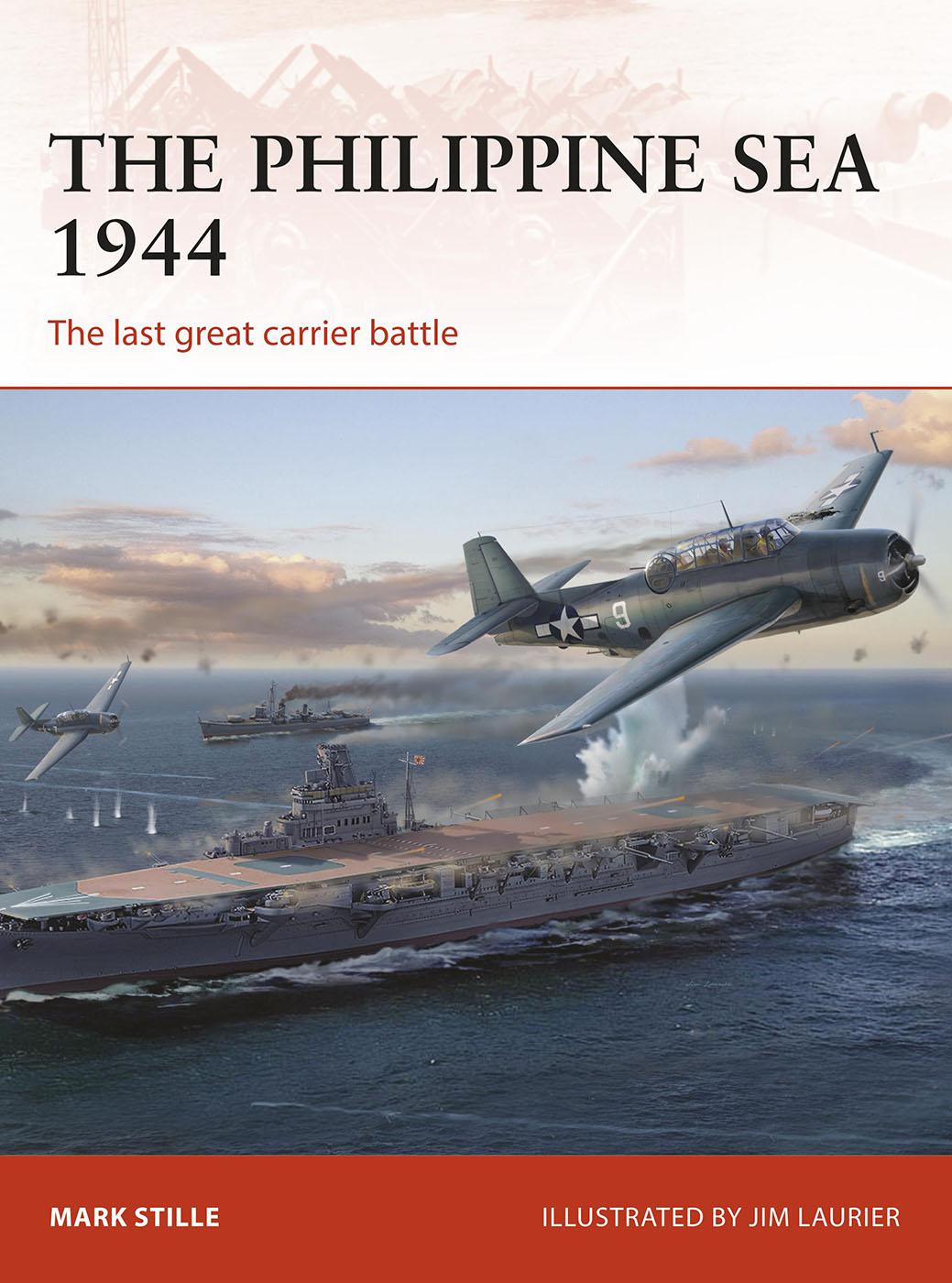

The battle of the Philippine Sea, fought in June 1944, has been somewhat overlooked compared to other major Pacific War naval battles. The encounter in the Philippine Sea was almost exclusively a carrier battle, the fifth of the Pacific War. As a carrier battle, it was by far the largest ever fought with 15 fleet and light carriers on the American side and nine on the Japanese side. By comparison, the second-largest carrier battle of the war, Midway, featured seven carriers. No other carrier battle of this magnitude will ever be seen again.

Strategic situation, June 1, 1944

Even ignoring the unique carrier aspect of this battle, it was an engagement of tremendous size. The United States Navy (USN) brought some 165 combatants to the action and almost 900 aircraft on the fleet and light carriers complemented by another 170 aircraft on seven escort carriers. The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) mustered over 50 combatants for this battle, and just over 400 carrier-based aircraft and more than 300 land-based aircraft. For sheer size alone, the battle of the Philippine Sea was the second-largest naval engagement of the Pacific War, surpassed only by the battle of Leyte Gulf fought a few months later.

Many accounts of naval warfare in the Pacific use the term decisive too readily when describing the principal naval battles of the war. In the case of Philippine Sea, the term is no exaggeration. The American objective of the battle was to seize the Marianas Islands that provided air bases for the long-range bombardment of Japan. The USN expected a major reaction from the IJN, so the destruction of the Japanese carrier fleet was another primary objective. The IJN had been hoarding its carriers for almost 20 months, and its commitment to defend the Marianas was planned to be a decisive encounter with the USN. In only ten days in mid-June, the Americans realized all their major objectives and the IJN suffered a decisive defeat. Most of its carriers escaped, but their aircraft and trained aircrews did not. This effectively meant the end of the IJN as a major threat to future American moves in the Pacific and led directly to the desperate and ill-conceived Japanese plan to defend Leyte in October that resulted in the final destruction of the IJN.

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

The Japanese advance during the initial period of the war was short lived. By August 1942, the Americans launched their first offensive in the Pacific, landing on Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. This resulted in a grinding battle of attrition that exacted heavy naval and air losses from the IJN. Losses to the USN were actually greater, but by late 1942 the flood of new American naval construction was reaching the Pacific and was already underwriting an accelerated American offensive. This increased strength could sustain offensives on two fronts. One was already underway, running up the Solomon Islands and then through New Guinea toward the Philippines and eventually China. The other was just starting from Hawaii through the Central Pacific. This basic outline for a two-front offensive against the Japanese for 194344 was approved at the Trident Conference held in Washington, DC on May 1217, 1943, by the Combined Chiefs of Staff from the United States and Great Britain.

The Central Pacific axis of advance was always the preferred option for the USN. It was a predominantly naval show under the command of Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, the Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas and of the United States Pacific Fleet. Admiral Ernest J. King, Chief of Naval Operations and Commander in Chief, United States Fleet, who was a trusted advisor of President Franklin Roosevelt and a member of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, strongly supported the Central Pacific option. However, lack of resources and command rivalry in the Pacific forced an alteration of the plans for a Central Pacific offensive. The original plan coming out of the Trident Conference called for the seizure of the Marshall Islands and the Caroline Islands. By July 1943, it was obvious that an attack on the Marshalls was logistically infeasible without drawing forces from the Southwest Pacific Area command under the control of General Douglas MacArthur, so the US Joint Chiefs ordered Nimitz to attack the Gilbert Islands instead with a target date of November 15, 1943.

This modified scheme was approved at the Quebec Conference held in Canada from August 17 to 24, 1943, and future Central Pacific operations were confirmed as sequential invasions of the Gilberts, Marshalls, Carolines, and then the Palau Islands. King was successful in inserting the Marianas as a possible substitute for the Palaus. After the conference, King was supported by General Henry H. Arnold, commander of the Army Air Forces, who wanted to use the Marianas as a base for mounting B-29 bomber attacks against Japan. The new B-29 had the range to fly from the Marianas to the Japanese Home Islands. Earlier attempts to get the B-29s within range of Japan by basing them in China had demonstrated the immense logistical challenges inherent in basing heavy bombers in a place where air supply was the primary method of moving the massive amount of the required men and supplies. It was apparent that if the Army Air Forces wanted to strike Japan, establishing bases in the Marianas was the only way to do it.

By the Cairo Conference of December 1943, the Allied leaders clearly saw the advantages of the Central Pacific drive and the benefits of seizing the Marianas in particular. The attack on the Marianas was scheduled for October 1944, following the seizure of the Marshalls in January and Truk in July. A Central Pacific campaign plan was issued by Nimitzs staff in December 1943 and revised in January 1944 with a projected November 1 invasion of the Marianas.

As the pace of operations quickened, the debate between Nimitz and MacArthur became more heated. At a planning conference in Washington, DC in February and March, the schedule for Central Pacific operations was examined again and altered significantly. MacArthurs staff fought for an advance along northern New Guinea into Mindanao in the Philippines. King was determined to keep his Central Pacific drive as the primary focus. When Nimitz joined the conference, he proposed two possible schedules for the remainder of the year. One called for Truk to be bypassed, Saipan in the Marianas to be attacked by June 15, and landings on the Palaus on October 1.

What was agreed to by the Joint Chiefs of Staff was Nimitzs short-term schedule, mixed with MacArthurs longer-term goal of invading Mindanao. The final sequence of operations was set as the occupation of Hollandia on the coast of northern New Guinea by MacArthurs forces with support from Nimitzs carriers on April 15, the bypassing of Truk, followed by the initial landings on the Marianas on June 15. Following this, the next targets were the Palaus in mid-September and Mindanao in mid-November.

As the Allied command staffs pondered the next move of the rising American tide in the Pacific, the advance continued to roll forward. On November 20, 1943 Tarawa and Makin Atolls in the Gilberts were invaded and fell within days. On January 31, 1944, Nimitzs forces landed on Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshalls. Eniwetok in the western Marshalls was seized after an operation beginning on February 17. Fighting was bitter on some of these islands, particularly on Tarawa, but at no point did the IJN attempt to mount a counterattack, and the issue was never in doubt on any of the islands with the possible exception of Tarawa.