THE IMPERIAL JAPANESE NAVY

IN THE PACIFIC WAR

MARK E. STILLE

Dedication

To my mother, Louise, who gave me the love of reading and writing.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the many people over the years who have contributed in ways large and small to my work on the Imperial Japanese Navy. Among the most gracious with their time were John Lundstrom, Allyn Nevitt, and Alan Zimm. This book would not have been as appealing without the outstanding collection of photographs which come from many sources. In particular, I would like to thank Robert Hanshew at the Naval History and Heritage Command, Tohru Kizu, editor of Ships of the World magazine, and the Yamato Museum.

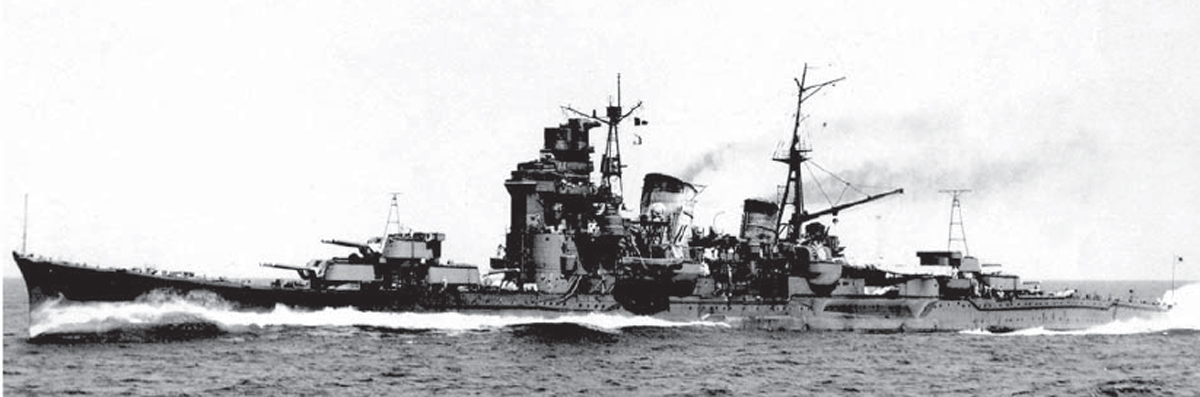

Sendai in 1939 acting as a destroyer squadron leader. (Yamato Museum)

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

At the start of the Pacific War in December 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) was the third most powerful navy in the world. This was an impressive achievement for an organization which had only been in existence since 1868. The meteoric rise of the IJN was due to a combination of factors, not the least of which was an accepted imperative to modernize in the face of a visible foreign threat, accompanied by able administration and willingness to adapt and innovate, and the assistance of first Great Britain and then other foreign countries. So quickly did the IJN modernize that it was able to defeat China in a war from 1894 to 1895, and then, to the astonishment of the world, vanquish a major European power in the Russo-Japanese War of 1904 to 1905.

The war against Russia culminated in a decisive battle in which the outnumbered Japanese battle fleet prevailed through its superior training and fighting spirit. This became a template for the IJNs next war, which would be fought against an even more daunting opponent the United States Navy (USN). The USN had gone from being a hypothetical adversary in 1907 to the only force able to block Japans imperial ambitions in 1941. The IJN had spent the entire interwar period preparing for war against the Americans and in 1941 went to war at the height of its powers and even enjoyed a numerical advantage over the USN, which had to devote resources to the Atlantic theater. In 1941, the balance was as favorable as it would ever be for Japan with the IJN honed to a fine edge and the USN not yet reinforced by the ships from its two-ocean navy building program which, if realized, would swing the naval balance drastically against the IJN.

The opening of war in December 1941 showed the IJN to be more than a match for the USN and Allied navies for the first six months of conflict. Not only did the IJN possess superior ships in most categories, but the training of their crews under virtual wartime conditions made them decidedly more combat ready than their enemies. As a result the IJN was virtually unchecked during the first phase of the war, during which it accomplished all its objectives for the loss of no ship larger than a destroyer.

The run of Japanese victories was stopped at Coral Sea and Midway in May and June 1942, but the IJN remained a formidable adversary as shown by its ability to outfight the USN during the Guadalcanal campaign from August 1942 until February 1943. This was the true turning point in the Pacific War since it inflicted severe attritional losses on the IJN in ships and aircraft, and, more importantly, in highly trained personnel, for no strategic benefit since the Japanese proved eventually unable to stop the first American offensive of the war. The campaign also indicated another Japanese weakness as tactical excellence proved to be no substitute for lack of strategic insight.

Into 1943, the IJN girded its strength for another decisive battle to turn the tide of the American advance. This occurred first in June 1944 at the Battle of the Philippine Sea, and again a few months later in October in the climactic Battle of Leyte Gulf. Both resulted in catastrophic defeats and by the end of October the IJN was no longer a viable force, which opened the Japanese home islands to the prospect of direct attack. From its initial sweeping victories in 1941 and early 1942 in the Pacific and Indian Oceans, the IJN was reduced in 1945 to mounting effective resistance only with suicide aircraft. The final gesture of committing the superbattleship Yamato, which symbolized the IJN and the Japanese nation, against overwhelming USN air power in April 1945 effectively marked the end of the short life of the IJN.

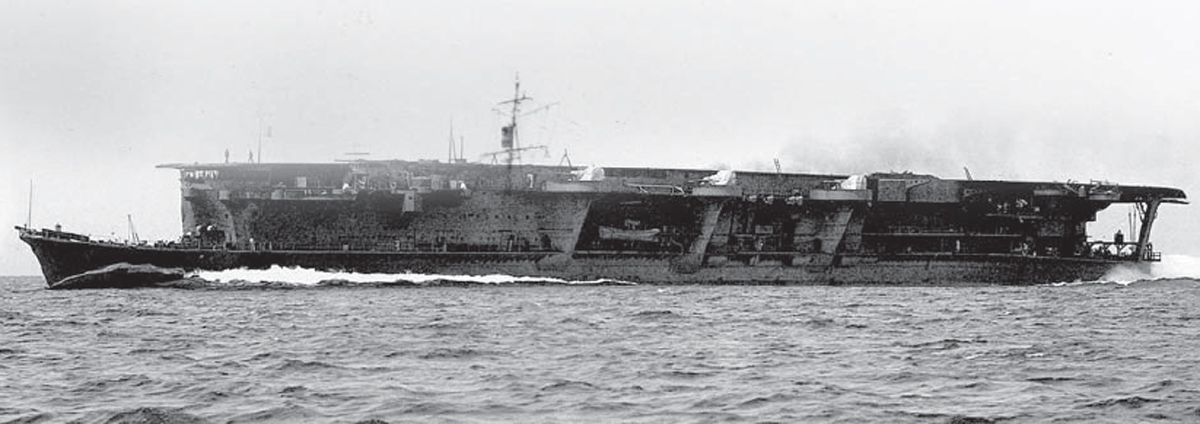

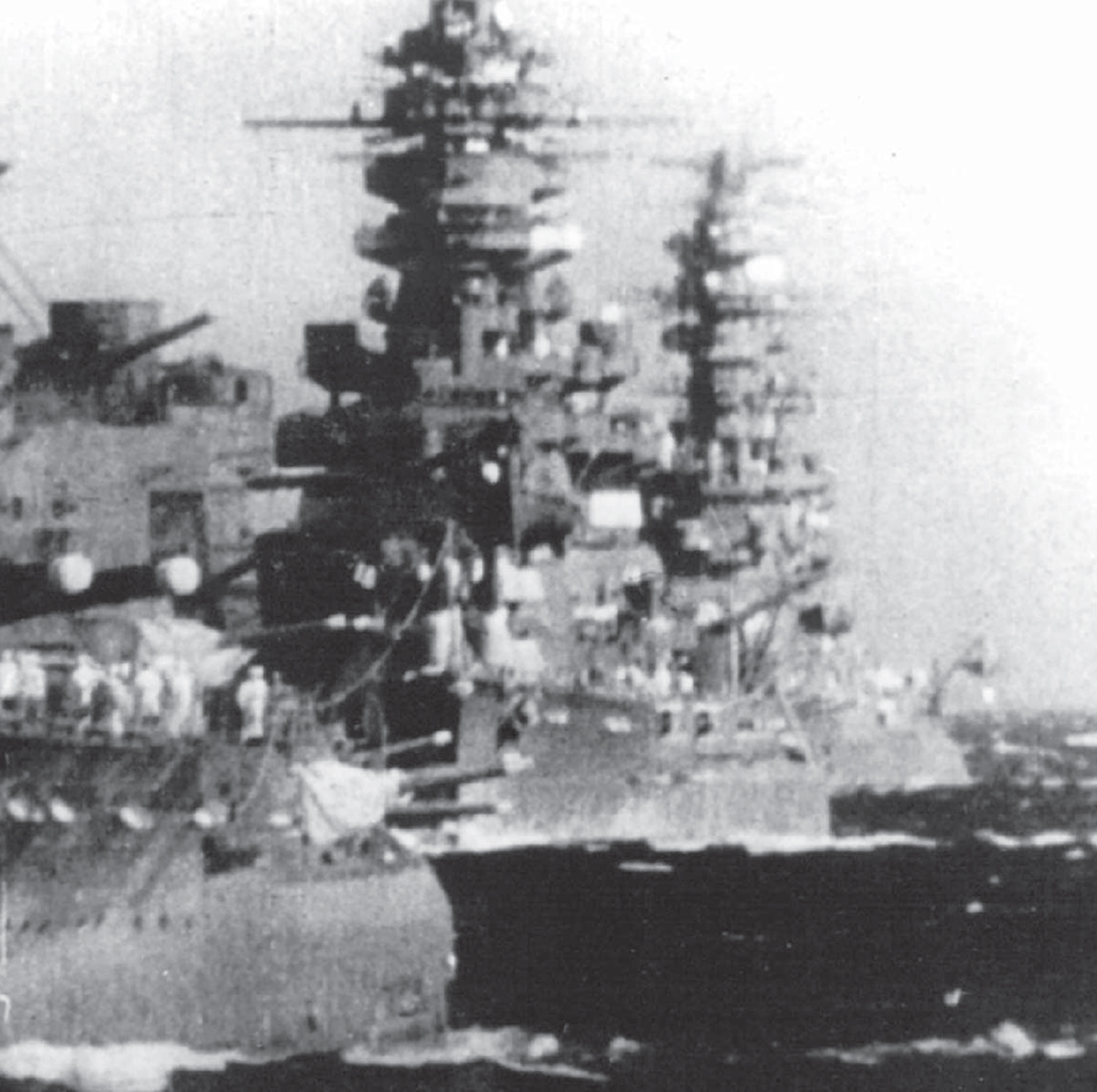

Mutsu, Ise, and Fuso in line-ahead formation, prior to the Pacific War. Like all navies of the interwar period, the strength of the IJNs battle line defined its status. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

IMPERIAL JAPANESE NAVY STRATEGY AND DOCTRINE IN THE PACIFIC WAR

DECISIVE BATTLE STRATEGY

Going into the Pacific War, the strategy of the IJN was underpinned by several key assumptions.

The most fundamental assumption was that, just as the Russo-Japanese naval war had been decided by the Battle of Tsushima on May 2728, 1905, the war against the USN would be decided by a single great naval clash. The nature of this battle was also believed to be certain, and this conviction was shared by both the IJN and the USN: the battle would be decided by the big guns aboard battleships. All other arms of the IJN were dedicated to supporting the dreadnoughts when they met the USN in battle. The place of the great clash between dreadnoughts was also sure, at least for the IJN. The Japanese assumed that at the start of any conflict, they would quickly seize the largely unprotected American-held Philippines. This would force the USN to mount a drive across the Pacific to retake them. Accordingly, the great clash would take place somewhere in the western Pacific when the IJN decided the time was right to stop the American advance.

Furthermore, it was clear to the Japanese that in order to win the decisive clash they would have to make up for a numerical disadvantage. The Japanese realized that they would never have the industrial capacity to create a navy equal in size to the USN, but, since they were planning on deriving the benefits of being on the defensive, they calculated that they had to have only 70 percent of the strength of the USN to be in a position to prevail in the great clash. This assumption was built on two pillars. Both became driving forces in IJN naval construction, tactical development, and training between the wars. The first was that the IJN had to have the weapons and tactics to inflict severe attrition on the USN before the decisive battle, which would bring the IJN to at least parity. Once at rough parity, IJN units with superior speed and capable of hitting at ranges beyond the reach of the USN, crewed by superbly trained personnel, would win the day.

THE WASHINGTON AND LONDON NAVAL TREATIES

The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 was one of historys most effective arms reduction programs, since it froze the construction of battleships for the next 14 years and affected the composition of all the worlds major navies. Because no major power was in a position to execute a large battleship-building program in the wake of the ruinous World War I, an agreement was relatively easy to reach. A system of ratios was set up between the five signatory powers. The United States and Great Britain were each allocated 525,000 tons of capital ships Japan had to be content with 60 percent of this at 315,000 tons (a ratio of 5:5:3). Italy and France were each restricted to 175,000 tons. A 10-year moratorium on battleship construction was agreed to. Replacement of battleships was allowed after they had reached 20 years of service, but none could be bigger than 35,000 tons or carry guns larger than 16in. Carriers were also restricted with the same 5:5:3 ratio, with Japans allocation being 81,000 tons.