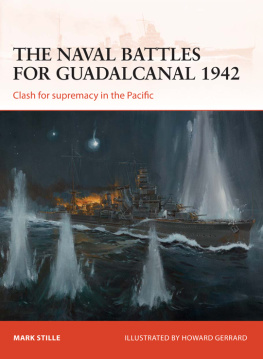

CAMPAIGN 255

THE NAVAL BATTLES FOR GUADALCANAL 1942

Clash for supremacy in the Pacific

| MARK STILLE | ILLUSTRATED BY HOWARD GERRARD |

| Series editor Marcus Cowper |

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Neither the United States nor the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) thought that the decisive battle of the Pacific War would be fought over an obscure island located in the southern Solomon Islands. Nevertheless, for six months from August 1942 until early February 1943, both navies found themselves locked in the most sustained naval campaign of the Pacific War, centered on the island of Guadalcanal. This campaign included seven major battles. Two of these were fought between carriers, but the other five, all at night, pitted the surface forces of the two navies against each other in a series of vicious, often close-quarter battles. Ultimately, the campaign was decided by the possession of the airfield on Guadalcanal. The Americans were able successfully to keep the airfield open throughout the campaign, making it difficult and ultimately impossible for the Japanese to move sufficient ground forces to the island to dislodge the Americans. At the conclusion of the campaign, both navies had suffered heavy losses. These were easily replaced by Americas growing wartime production, but, for the Japanese, the losses were crippling. Guadalcanal was the first stop on the long road to Tokyo.

ORIGINS OF THE CAMPAIGN

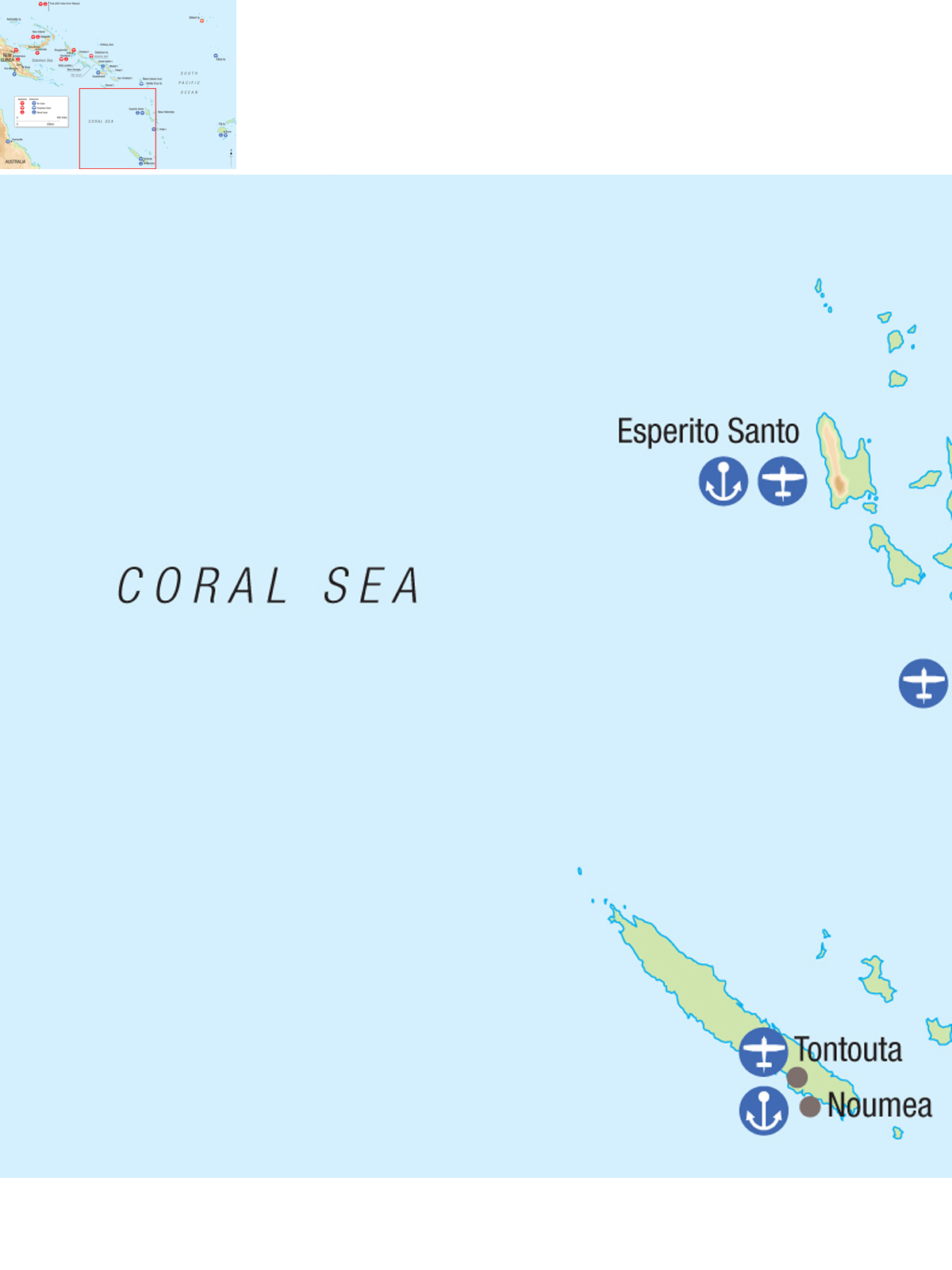

Occupation of Guadalcanal was not envisioned in Japans prewar expansion plans. In the First Operational Phase, the Imperial Army and Navy jointly agreed to occupy the Philippines, Malaya, the Dutch East Indies, Burma, and Rabaul. This went largely as planned. Rabaul, on the island of New Britain in the South Pacific, was occupied in January 1942. Rabaul possessed a large harbor and several airfields and was an ideal jumping-off location for further expansion in the area.

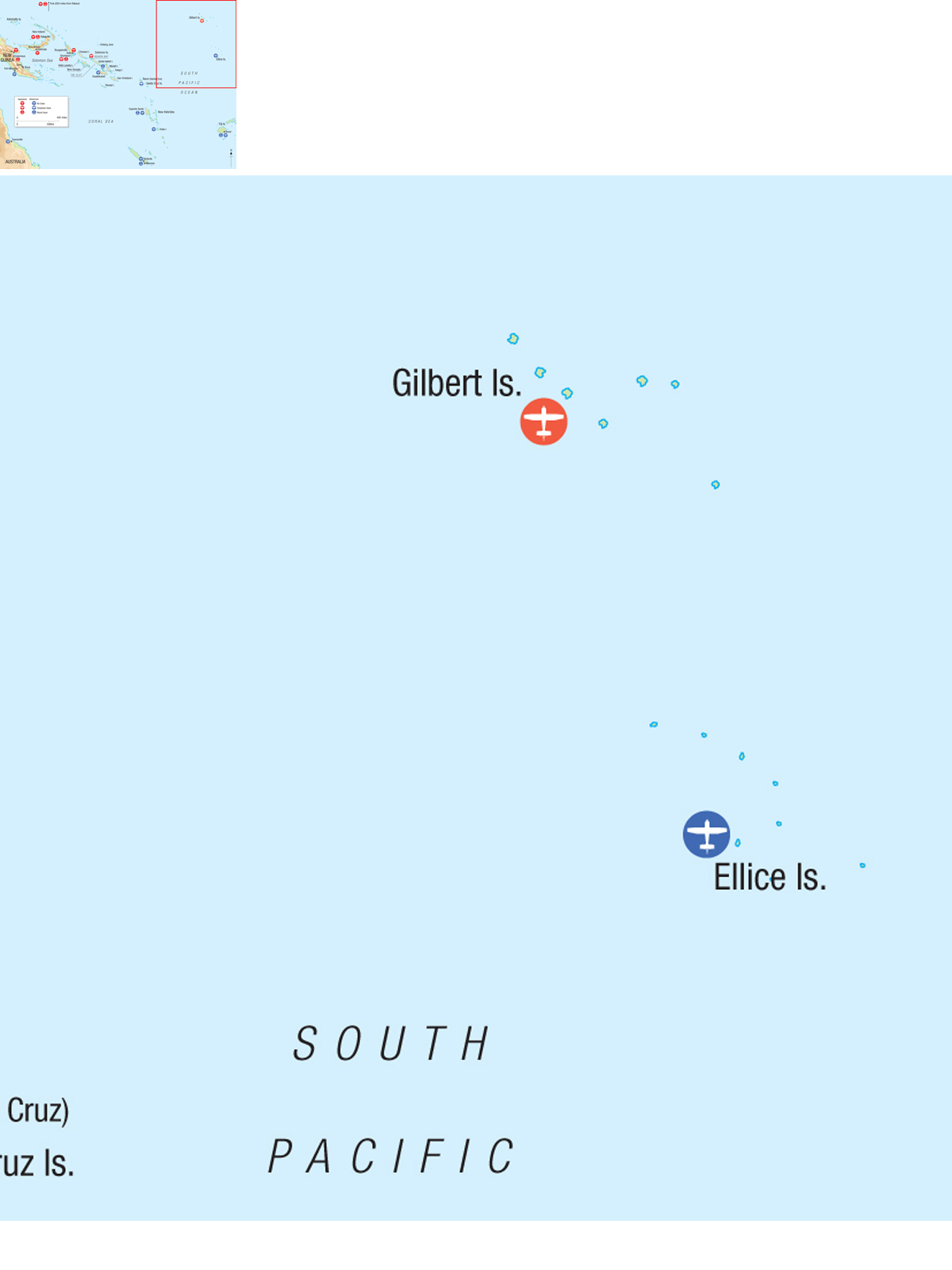

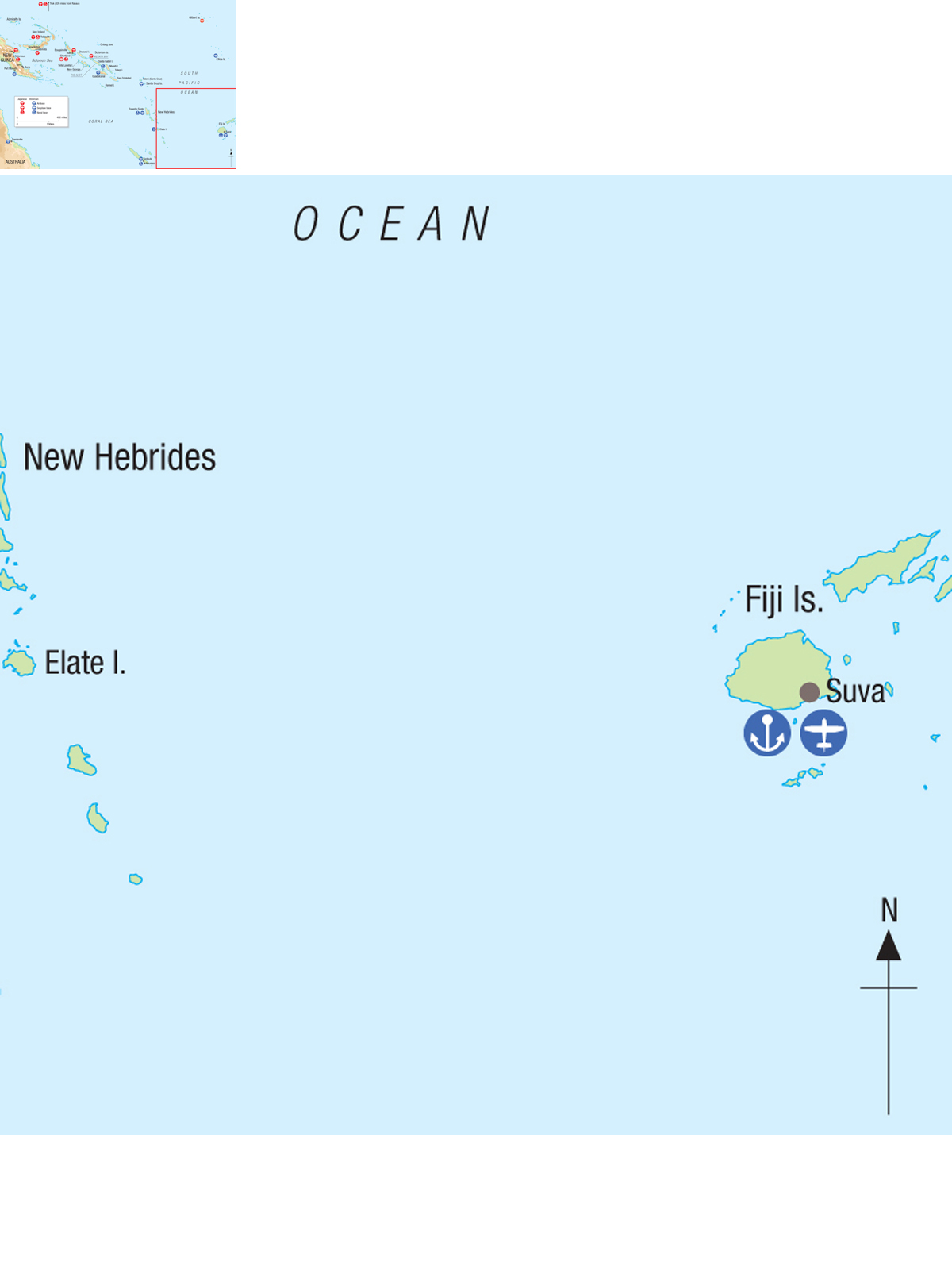

After the easy successes in seizing the First Operational Phase objectives (with the exception of the Philippines, which were not entirely occupied until May), the Japanese faced the question of where to advance next. As always, the availability of shipping was the primary limiting factor, though Japans ground and naval forces were already being stretched. The goal of the Second Operational Phase was to provide strategic depth to Japans defensive perimeter. In addition to the Aleutians and Midway, much of the anticipated future expansion would occur in the South Pacific. Eastern New Guinea, the Fijis, Samoa, and strategic points in the Australian area were all targeted. However, the Japanese could not agree on the validity of these objectives or the sequencing of the operations. Within the IJN, the commander of the Combined Fleet, Fleet Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku and the Naval General Staff had very different priorities. Yamamoto wanted to move first into the Central Pacific with the goal of drawing the remaining units of the US Pacific Fleet into battle and destroying them. The Naval General Staff advocated an advance into the South Pacific to cut the sea lines of communications between the United States and Australia. For its part, the Imperial Army favored operations that required minimal numbers of ground forces. This ruled out an attack on Australia, but operations against smaller South Pacific islands remained possible.

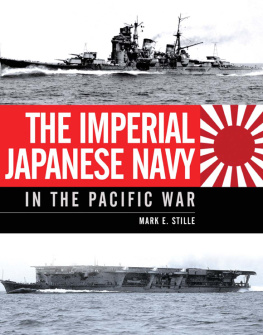

The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 forced the war in a direction unexpected by both sides. Instead of a large clash of battle lines, aviation was paramount. When surface actions did occur, it was between cruisers and destroyers, like those off Guadalcanal. (Naval History and Heritage Command, 80-G-30550)

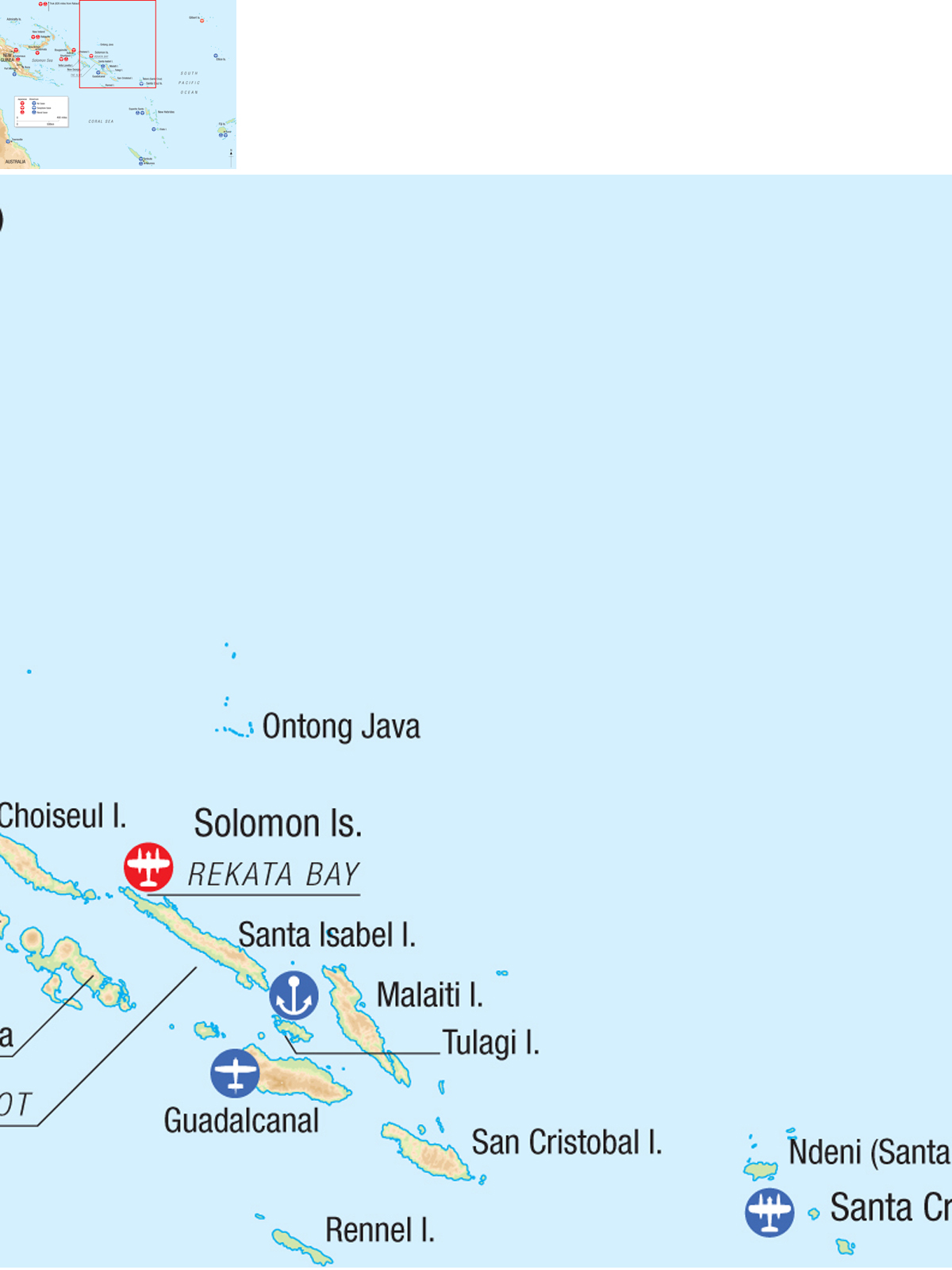

Though the Naval General Staff was the organization responsible for the formulation of Japanese naval strategy, Yamamotos views largely prevailed. Just as he had in the planning period before the Pearl Harbor operation, he used the threat of resignation to get his way. However, the decision reached in the first week of April was a compromise that called for an advance into both the South and Central Pacific in the span of two months. The first operation was set for May with the goal of seizing Port Moresby on New Guinea. Part of this operation was the occupation of Tulagi Island in the southern Solomons. Tulagi could be used as a seaplane base and was located some 20 miles north of Guadalcanal.

Japanese preparations for a major operation into the South Pacific did not escape the notice of the Americans. The Commander of the US Pacific Fleet, Admiral Chester Nimitz, dispatched two carrier groups to contest the Japanese advance. This resulted in the first carrier battle of the war in the Coral Sea on May 78, 1942, and the first strategic Japanese defeat of the war since the invasion of Port Moresby was halted. However, Tulagi was occupied according to plan on May 3, which gave the Japanese a foothold in the southern Solomons.

Another result of the Coral Sea battle was the fatal undermining of Yamamotos clash with the American fleet in the Central Pacific. None of the three Japanese carriers committed to the Port Moresby operation was able to participate in the Midway operation in June. This significantly reduced Yamamotos carrier advantage over Nimitz, and, combined with weak operational and tactical planning, resulted in a disaster for the IJN. All four of Yamamotos fleet carriers committed to the operation were sunk. These losses blunted Japans naval offensive capabilities. Following the Midway debacle, the Japanese made no attempt to maintain the initiative they had held since the beginning of the war. But the Japanese were not entirely passive. On June 13, they decided to build an airfield on Guadalcanal. Accordingly, on July 6, a 12-ship convoy arrived with two construction units to start work on the airfield, which was expected to be completed in August. Possession of an airfield on Guadalcanal would give the Japanese control over much of the South Pacific.

THE AMERICAN RESPONSE

Admiral Ernest King, Commander-in-Chief US Fleet, had been focused on the South Pacific since the beginning of the war. He made the defense of the sea lines of communication to Australia a major priority. Even though overall American strategy called for the primary effort to be made in Europe, King did not think that meant he had to be totally passive in the Pacific. As early as March 1942, King admitted that he had no intention of remaining strictly defensive but envisioned an offensive up the Solomons to retake Rabaul. In the aftermath of the Midway victory, which removed the Japanese offensive threat in the Central Pacific, King moved quickly to grab the initiative and launch a limited offensive in the South Pacific.