MARK STILLE

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

On August 7, 1942 the course of the Pacific War between the United States and Japan, now eight months old, took a new turn. On this date the US Navy mounted its first offensive of the war, landing on the island of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands. This first tentative attack prompted a fierce struggle between the US and Imperial Japanese navies, which was to last from August 1942 until February 1943 when the Japanese were finally forced to withdraw from the island. During this time, the two navies fought a total of seven major battles. Two of these, Eastern Solomons and Santa Cruz, were battles between carrier forces. The remaining five were fought between the surface forces of the two navies.

Before the war, both sides expected the question of naval supremacy in the Pacific to be decided by a decisive clash of battleships somewhere in the western Pacific. But the advent of air power and the unexpected scope of Japanese expansion during the initial stages of the war changed that. The US battle line had been crippled at Pearl Harbor and the Imperial Navy preferred to keep the majority of its battleships in home waters in expectation of the decisive battle. When the focus of Pacific naval combat shifted to the south Pacific, following the US landing at Guadalcanal, the bulk of each navys surface power resided in its cruiser forces. Both sides retained powerful carrier forces after the Battle of Midway, but the limited number of carriers and their demonstrated fragility meant that they were committed only for major operations. With battleships too valuable and potentially vulnerable to be exposed in the confined waters around Guadalcanal, especially at night, this left the cruiser as the major combatant surface ship during the initial parts of the Guadalcanal campaign.

In August 1942 both sides possessed large cruiser forces. In heavy cruisers the Imperial Navy held a numerical, and arguably a qualitative, advantage. Beginning in 1926, the Japanese had added 18 heavy cruisers to their fleet. One of these had been sunk in June 1942 and another so heavily damaged it would not return to service until 1943. The remaining 16 ships were an instrumental part of Japanese naval doctrine and were expected to play key roles in any clash with the Americans. By contrast, Japanese light cruisers were designed to operate in conjunction with the Imperial Navys destroyer flotillas and were not capable of acting as part of the battle line unlike the heavy cruisers.

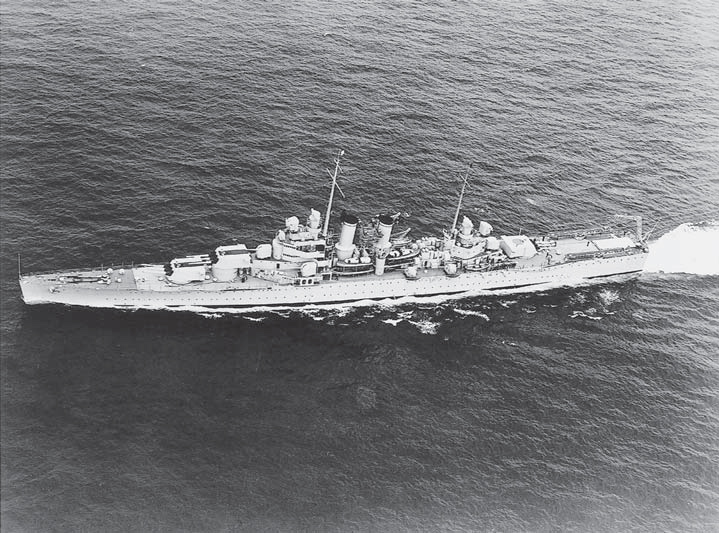

Minneapolis shown in November 1942 after taking two torpedo hits from Japanese destroyers. One hit took off the bow as far back as Turret 1 and the second flooded Number 2 fire room. Despite pre-war doubts about their ability to withstand damage, US Navy Treaty cruisers often displayed an ability to take heavy damage, as shown here. (US Naval Historical Center)

The US Navy had also invested heavily in its cruiser force before the Pacific War. Before the war, a total of 18 heavy cruisers had been built; however, since the US had commitments in two different oceans, not all of these were available for use in the Pacific. Before August 1942 one of these had already been lost to Japanese action, so coming into the Guadalcanal campaign the US Navy suffered from a numerical disadvantage in heavy cruisers. In part, this was compensated for by a number of light cruisers that were much larger than their Japanese counterparts. Nine large light cruisers were commissioned before the war and most were assigned to the Pacific theater. Added to this, the first of the Atlanta-class light cruisers laid down just before the war were coming into service by the time the struggle for Guadalcanal began.

Of the five major surface battles fought during the struggle for Guadalcanal, two were contested by forces led by cruisers, and both of these occurred during the initial part of the campaign. The first was the Battle of Savo Island, fought on August 9 immediately after the American landing. Aside from Pearl Harbor, this was the single most disastrous clash for the US Navy during the war and it clearly showed the Japanese cruiser force at its best. Two months later, by contrast, during the Battle of Cape Esperance, an American cruiser force would out-duel a Japanese cruiser force in another confusing night clash. However, these were the last pure cruiser battles fought during the campaign, as in November 1942 the struggle for Guadalcanal came to a head and in two climactic naval clashes between November 13 and 15, both sides also committed battleships. Later, on November 30, a Japanese destroyer force dealt an embarrassing reverse to an American cruiser force in the Battle of Tassafaronga. Because they involved forces based around cruisers on both sides, the battles of Savo Island and Cape Esperance will be used as models to examine the design strengths and weaknesses as well as the employment doctrines of both Japanese and American cruisers.

The battles around Guadalcanal, while costly for both sides, did not prove in themselves to be decisive for the surface fleets of either side. The US Navy suffered more heavily in these battles, but finally learned the techniques necessary to conduct successful night combat against the Japanese. The design of US Navy pre-war cruisers proved sound and flexible enough to allow them to perform in a number of roles for the remainder of the war. For the Japanese, the results of the Guadalcanal campaign were particularly dire. Though the vast majority of the Imperial Navys cruisers survived the Guadalcanal campaign, their employment in the fierce battles off Guadalcanal did not the pay the Japanese the dividends they expected. The attrition begun during the Guadalcanal campaign would continue into 1943 as the battle moved to the central and northern Solomons. As the Japanese became more reluctant to commit ships as large as heavy cruisers to these night actions, the Imperial Navys destroyers were forced to shoulder the burden, a task that eventually gutted the destroyer force. As air power played an increasingly dominant role throughout the Pacific, never again would surface forces play such an important role as they did during the cruiser duels of 1942.

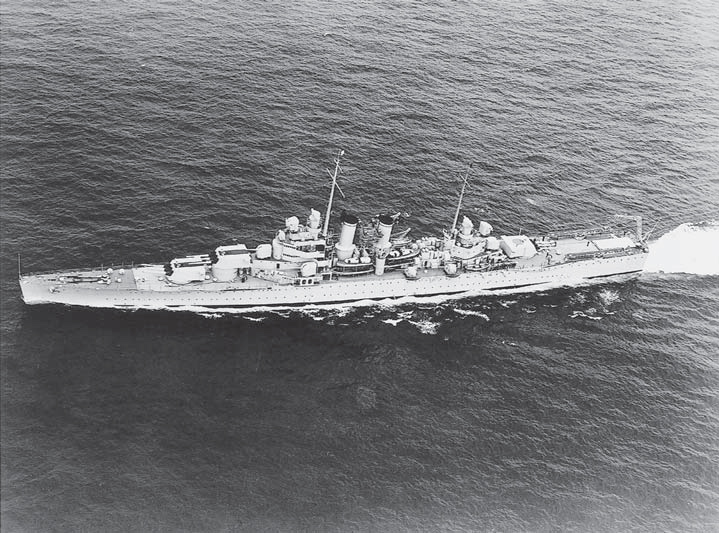

Wichita pictured in May 1940, clearly showing the hull design similarity to the Brooklyn-class light cruisers. The substitution of 8-inch guns is evident, as is the unique arrange of the ships secondary battery consisting of a combination of eight single 5-inch guns in open mounts and turrets. (US Naval Historical Center)

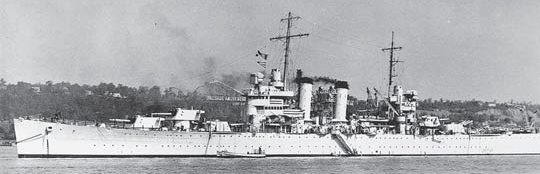

Brooklyn pictured after her completion in 1937. The arrangement of her five triple 6-inch gun turrets is evident. (US Naval Historical Center)