All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the publisher in writing.

Charlie Clancy |

Geoff Kitchen |

This book is dedicated to the memory of Charlie Clancy

(19152009), a survivor from HMS Cornwall, and Geoff Kitchen

(19232011), a survivor from HMS Dorsetshire. Charlie is, of course,

my dad and although I knew about the sinking of these two ships for a

number of years through stories he had told me, it was not until

I met Geoff in 2001, quite by accident whilst on holiday, that I began

to appreciate the full implications of this action.

I am indebted to Geoff for encouraging me to write this book and

giving me free access to his extensive archive. I raise my

hat to both of these gentlemen.

Acknowledgements

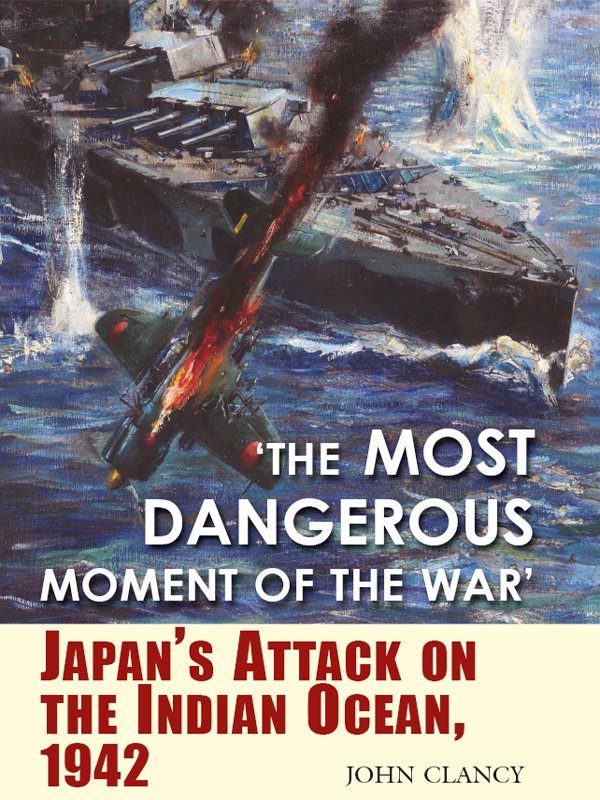

The front cover picture is taken from a painting by Terence Cuneo CVO OBE RGI (19071996). Entitled Aircraft Attack British Battleship, it was originally painted for the Ministry of Information during the Second World War whilst Cuneo was serving as a Sapper but he also worked for the War Artists Advisory Committee, providing illustrations of aircraft factories and wartime events. Cuneo was an eclectic painter and after the war was commissioned to produce a series of works illustrating railways, bridges and locomotives, but a significant point in his career was his appointment as official artist for the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, which brought his name before the public worldwide. He received more commissions from industry, covering manufacturing, mineral extraction and road building, including the M1 motorway. He was famous for his passion for engineering subjects, particularly locomotives and the railway as a whole, but in fact Cuneo painted over a wide range of subjects, from big game in Africa to landscapes. Further success was achieved in his regimental commissions, battle scenes and incidents as well as portraits, including Field Marshall Montgomery. In recognition of the respect people have for Cuneo, a 1.5-times life-size bronze memorial statue of him, by Philip Jackson, stands in the main concourse at Londons Waterloo Station. It was commissioned by the Terence Cuneo Memorial Trust, established in March 2002, as a permanent memorial to the artist. The Trust also provides an annual prize at the Slade School of Art, Cuneos former school.

It is sometimes difficult for writers to produce an accurate picture of past events, particularly when trying to assess how the people involved discharged their duties and responsibilities, when they themselves were not present. I myself fall into this category but I think my training as anarchaeologist will stand me in good stead, for I am used to researching a subject, gathering together all the available evidence, the facts and the figures, from a number of different sources, and piecing it together coherently, rather like a jigsaw puzzle. The only thing we cannot say with any certainty is why certain people did what they did at the time. To know this you would need to be inside that persons mind because not even he who stood next to that person would truthfully be able to say. We can only offer our best guess based on the evidence before us, which is what archaeologists are particularly adept at. For this reason I have drawn to some extent on the works of other writers whose books appear in the section headed Further Reading and I take this opportunity to acknowledge them.

This book is dedicated to the memory of all of those who took part in these operations in the Indian Ocean and Ceylon between March and May 1942, especially those who were killed in action. And whether you approve or not, for I know many will not, we cannot fail to extend this tribute to the enormous efficiency and fighting spirit of the Japanese forces who opposed us, despite them sometimes being guilty of barbaric acts of treatment towards their prisoners, but then that is a fundamental part of their militaristic culture and code of conduct. But it is no excuse for their flagrant disregard of the Geneva Convention.

Every effort has been made to authenticate the information received from various sources but sometimes time can play tricks on the memory so if any part of my text is inaccurate I sincerely apologise and will endeavour to correct it in any future editions of this book. Every reasonable effort has been made to trace and acknowledge the copyright holders of the pictures used herein but should there be any errors or omissions or people whom I could not contact, I will be pleased to insert the appropriate acknowledgement in any future editions.

John Clancy, BA (Hons), MA

Introduction

War in the Far East erupted with the most spectacular and successful bombing raid ever seen; that fateful day at Pearl Harbour on 7th December 1941 will live on in the annals of infamy. Over the next eighteen months results almost as spectacular were claimed, but nothing compared with the attack on Pearl Harbour. Even though the Americans had good reasons for expecting the attack, given that war between Japan and the United States had been a possibility of which each nation had been aware (and developed contingency plans for) since the 1920s, the enormous surprise which the Japanese managed to achieve was totally unexpected, even by their own pilots, so when these same airmen came to attack Ceylon some four months later, the British, despite having extremely accurate and comprehensive intelligence of Japanese intentions, were taken only a little less by surprise.

Without wishing to appear to be overstating the events that took place in and around Ceylon, or Sri Lanka, in March and April 1942 too highly, such was its extent and magnitude it could so easily have become known as Pearl Harbour, Part II. To the Japanese it was known simply as Operation C, a naval sortie by their fast aircraft carrier strike force under the command of Vice-Admiral Chuichi Nagumo against Allied shipping and bases in the Indian Ocean in an attempt to force the Allies to retreat to East Africa, thus leaving the Japanese unopposed in the Indian Ocean.

Ceylon remembers it as The April Raids; Sir Winston Churchill later described it as being so dangerous to our cause; and the historian, Sir Arthur Bryant said, A Japanese naval victory in April 1942 would have given Japan total control of the Indian Ocean, isolated the Middle East and brought down the Churchill government. It was a situation aggravated by the possibility that at the same time the Germans couldhave captured Egypt and closed our routes to the Middle East. It is all too easy to overlook the gravity of these events or to underrate the concern that prevailed as the Japanese swept westwards, brushing aside any opposition. There seemed to be no holding them back and in early April 1942 over a thousand lives, mostly British, were lost as the Japanese made their only major offensive of World War II westwards. It has even been questioned why a film has never been made about this incident because like the attack on Pearl Harbour, it has all the necessary ingredients to become a blockbuster.