Pagebreaks of the print version

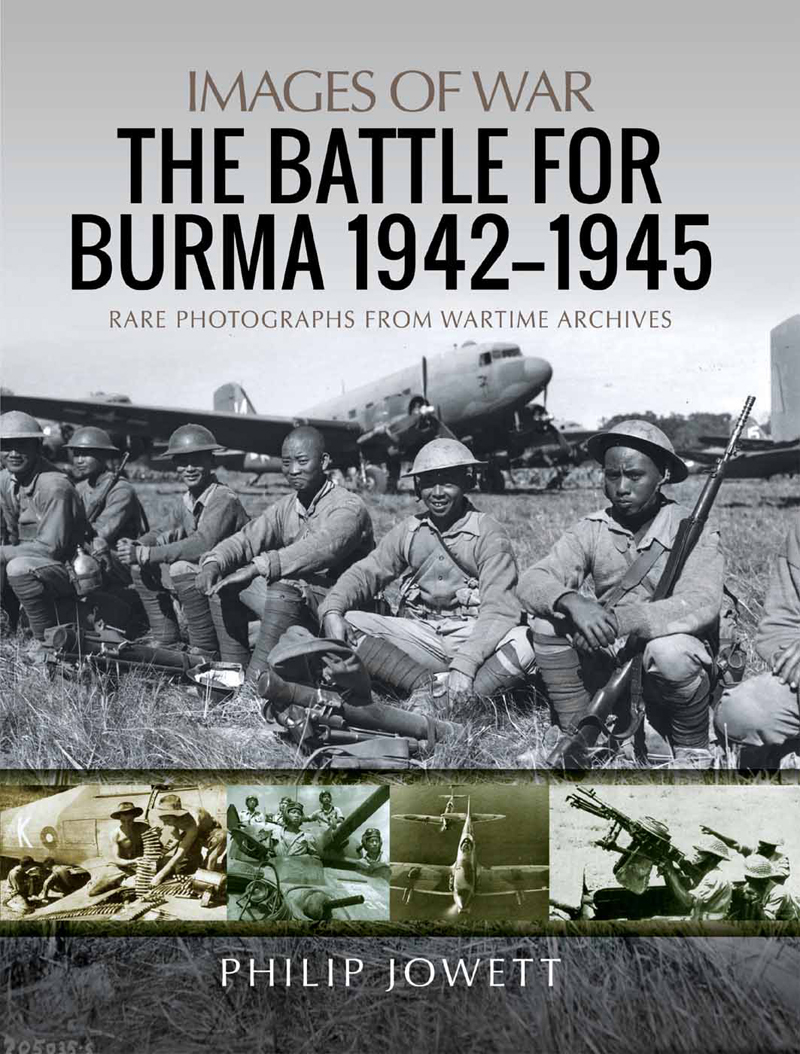

IMAGES OF WAR

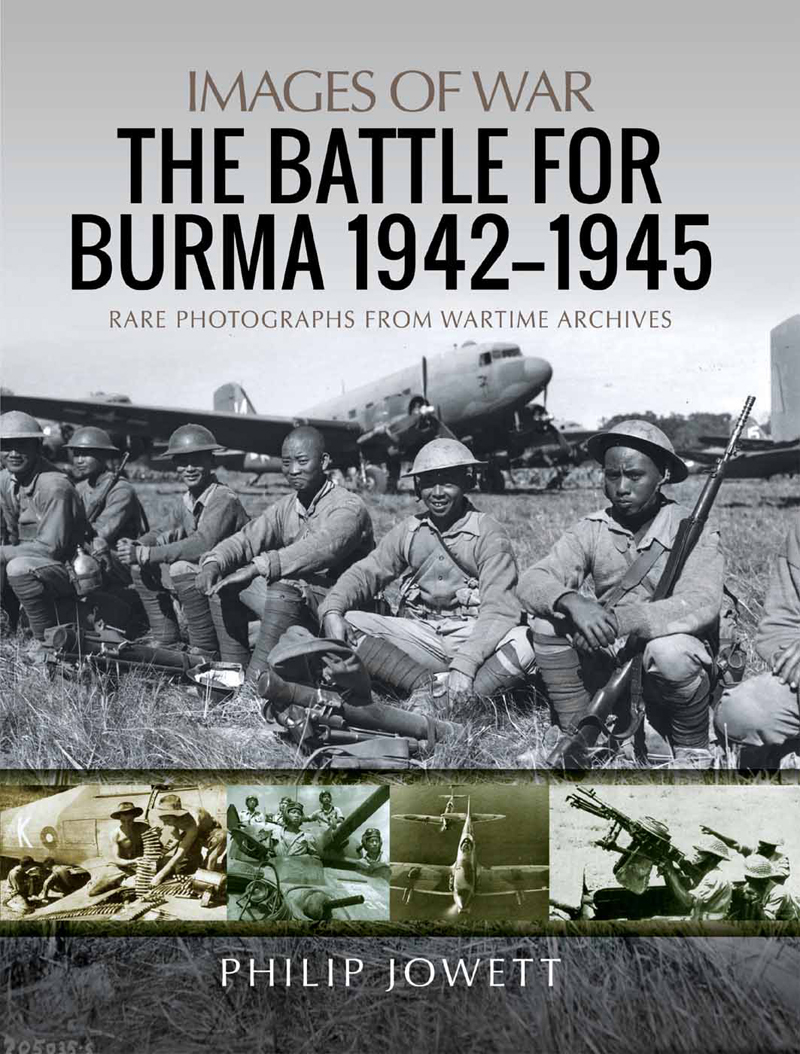

THE BATTLE FOR BURMA 19421945

RARE PHOTOGRAPHS FROM WARTIME ARCHIVES

PHILIP JOWETT

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by

PEN & SWORD MILITARY

An imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Yorkshire Philadelphia

Copyright Philip Jowett, 2021

ISBN 978-1-52677-527-6

eISBN 978-1-52677-528-3

Mobi ISBN 978-1-52677-529-0

The right of Philip Jowett to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Aviation, Atlas, Family History, Fiction, Maritime, Military, Discovery, Politics, History, Archaeology, Select, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe True Crime, Military Classics, Wharncliffe Transport, Leo Cooper, The Praetorian Press, Remember When, White Owl, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LTD

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

or

PEN & SWORD BOOKS

1950 Lawrence Rd, Havertown, PA 19083, USA

E-mail:

Website: www.penandswordbooks.com

This book is dedicated to ex-Chindit Private Charles Jowett, 2nd Battalion, The Duke of Wellingtons West Yorks Regiment, who participated in Operation Thursday in 1944.

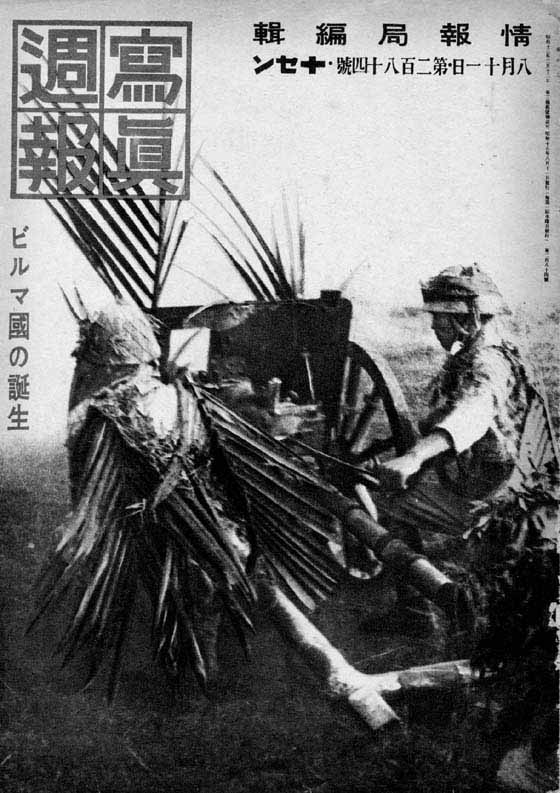

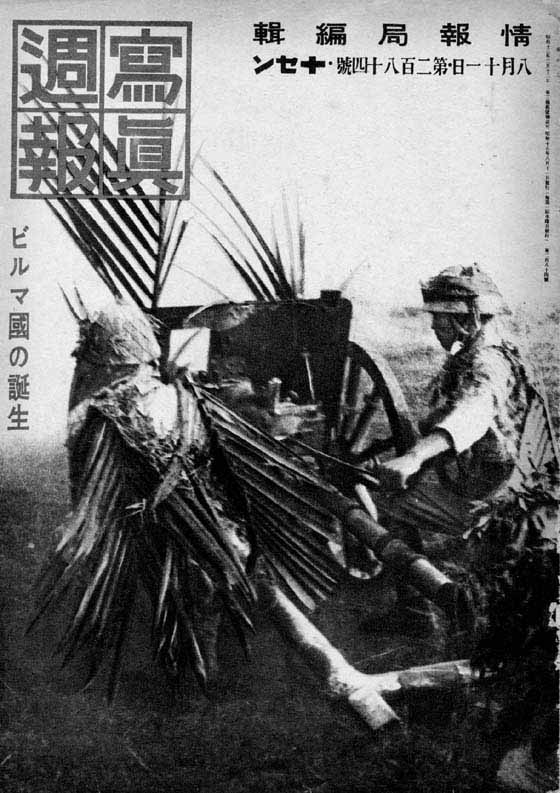

The front page of a Japanese pictorial magazine shows a crew moving their camouflaged Type 41 75mm regimental gun into position. This gun had been modified from the original 1908 version by putting it onto a more lightweight carriage. It could be broken down into six parts but was light enough to be moved around by its crew from firing position to firing position. ( Authors Collection )

Introduction

J apan entered the Second World War in early December 1941 and at the same time brought the USA into the conflict. The Japanese attack on the US Pacific Fleet on 7 December was followed by a highly successful land and sea offensive. This offensive, through South-East Asia and the Pacific, destroyed the imperial control of the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies and British-ruled Malaya, Borneo and Burma. By May 1942 the Japanese ruled an empire that included most of South-East Asia and the islands of the western and central Pacific. British-ruled Burma had never been a priority for the Japanese and the plan was only to take control of the south of the territory for strategic reasons. The unexpected collapse of the British forces in Burma ended in May 1942 with the complete takeover of the whole of the colony. Defeated British and Indian troops, along with some Chinese Nationalist troops sent to aid them by Chiang Kai-shek in early 1942, retreated northwards. They were pursued by the Japanese until their remnants crossed the Indian-Burmese border to try to lick their wounds. Meanwhile the Allies assessed the sheer scale of their defeats and the threat of the new triumphant Japanese Empire.

For the British and their new US allies, the liberation of Burma from Japanese rule was simply not a priority. The Allies priority was always going to be the defeat of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy, who were now allied to Imperial Japan. They were far more concerned with the crucial fighting in North Africa in late 1942 and 1943, and Burma simply did not have the strategic value of other fronts during the Second World War. The jungles of Burma were seen as a sideshow and were to be regarded as the Cinderella front for the rest of the war. A main reason for fighting Japan in Burma in 1943 and early 1944 was to try to keep Nationalist China in the war. From the Japanese viewpoint, Burma was seen mainly as a bulwark against Allied attacks into the rest of Japanese-controlled South-East Asia. Increasing speculation about the possibility of invading British India would, of course, involve Burma and the Japanese forces stationed there. It was hoped that Burmas difficult terrain and climate would be sufficient deterrent to any attacks from India.

Burma, some 250,000 square miles in area, was the size of France and Belgium combined and the tropical climate was extreme, with the temperatures in the plains reaching unbearable levels in the summer heat. Rainfall was at least 200 inches per year, increasing to as much as 800 inches in the western region, Arakan. The annual monsoon began in May, with an average rainfall of 20 inches per week, which was usually sufficient to bring any fighting to a standstill. The Burma campaign saw the combatants fighting through the monsoons of 1943, 1944 and 1945. In the western and eastern parts of the country there were great mountain ranges running north to south, covered in thick jungle. The western part of the country on the border of India had mountain ranges that were 600 miles long and 200 miles deep. On the eastern side of Burma, bordering Thailand and China, were high mountains and deep gorges that made travel difficult, to say the least. Several major rivers notably the Irrawaddy and its tributary the Chindwin, the Sittang and the Salween ran down the length of Burma. In central Burma there were areas that had little or no jungle, and here rice was grown. The difficult climate in most of Burma, with its heat and high humidity, led to a high incidence of tropical diseases. Malaria, scrub typhus, dysentery and cholera were rife in many areas of Burma, and both Allied and Japanese soldiers suffered terribly during the fighting. As well as these dangers, the presence of blood-sucking and biting and stinging insects and millions of leeches made everyday life even more difficult.

Chapter One

Burma

19423

A t the end of the disastrous Burma campaign of 19412, some 12,000 British and Indian troops and some Chinese marched wearily into the relative safety of India. The vast majority of these troops were in no state to fight, with only 2,000 of them being classed as 100 per cent fit. Most of the others were in various states of exhaustion and were malnourished and disease-ridden. It was not just the military who had suffered during the fighting, and there were thousands of mainly Indian civilians wanting to leave Burma. An estimated 400,000 Burmese and Indians had fled into India, with at least 10,000 dying on the arduous journey. Most of the Indians had been either traders or migrant labourers, and they did not want to stay under the rule of the Japanese. Thankfully for the British military and Indian civilian survivors, once they crossed the Chindwin river the Japanese abandoned their pursuit. The start of the Burmese monsoon also gave the defeated British some breathing space as the Japanese were too weary to fight during the wet season. One Japanese officer, Colonel Hayashi, argued for the continuation of the offensive with the aim of capturing the Indian-Burmese border city of Imphal, to prevent the Allies from using the city as a forward base for ongoing fighting. His arguments found favour with some military planners in Tokyo but the man on the ground, General Iida, knew his men needed a rest. The Japanese offensive came to a virtual stop, but there were clashes between patrols along the Chindwin river. The 23rd Indian Division had moved up to the border from its bases in India to cover the withdrawal of the defeated British-Indian Army, and established a defence line along the Chindwin river behind which the defeated troops began to recover. Many were sent to Imphal, the Indian state capital of Manipur, some 50 miles from the Burmese border, which now took on a new strategic importance as this usually sleepy city became the main base for the Allied war effort on the Burma front and was transformed over a few months into a busy headquarters for the Allied armed forces. The situation in Imphal was chaotic to say the least, with the Japanese expected to move on the town at any time. Fortunately for the British, the Japanese were busy consolidating their position in a territory they had never planned to conquer in the first place. They did not think of pushing into India to liberate the oppressed population of the most prized British imperial possession. Under cover of the 1942 monsoon season, the Allied commanders in Imphal began to improve the infrastructure, which was sorely lacking. Roads leading to the town from the rest of India were improved and three airfields were built to accommodate the first RAF reinforcements that began to arrive.