About the Author

FELICITY GOODALL is a writer and broadcaster and the author of five popular history books. She is particularly interested in the human cost of war, and has written on conscientious objection in the First and Second World Wars, and the Home Front in 193945. She has also written and directed a Radio 4 play about the first woman to be accredited as a war correspondent by the British Army. Her father volunteered for the army, serving in the Royal Engineers in the Burma campaign from 1943 to 1945. She is currently working on a novel set in Burma during the Second World War. http://felicitygoodall.wordpress.com/

For Pat Givan

Godmother, mentor and friend

Cover illustration. Escaping across the river. The British Library Board

(Mss Eur E 338/6)

First published in 2011

Updated paperback edition first published 2017

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

This ebook edition first published in 2011

All rights reserved

Felicity Goodall, 2011, 2017

The right of Felicity Goodall to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

EPUB ISBN 978 0 7524 6664 4

Original typesetting by The History Press

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

Contents

Acknowledgements

My name may be on the cover, but without the people below, this book would not have been possible. Principal among these is my godmother Pat Givan, and for her generosity and kindness I thank her. My husband Alan Denbigh, and sons Thomas and Stephen have supported and encouraged, and put up with long absences. My father Stephen Goodall lent books and shared recollections, and my niece Katie Pearson put up with me during my London research trips.

I am indebted to Roderick Suddaby, Keeper of Documents at The Imperial War Museum, who first pointed me in the direction of material on the trek out of Burma. It is a wonderful place to work thanks to the staff in the Reading Room, in particular Head of Documents and Sound Archives Tony Richards, and archivist Simon Offord. In another excellent institution, the British Library, I would like to thank the staff in the Asian and African Studies Reading Room, in particular Arlene Callender and Jeff Kattenhorn. Barbara Roe, Kevin Greenbank, and Annamaria Motrescu in the archives at the Centre of South Asian Studies at Cambridge University, were similarly helpful and accommodating, and for that I thank them. George Streatfeild and David Read at the Soldiers of Gloucestershire Museum were invaluable and traced references to Gordon Mellalieu. I would also like to thank all those who have given copyright permission, in particular Sterling Seagrave for permission to include extracts from A Burma Surgeon by his father Gordon Seagrave; Sir Eric Yarrow who also allowed me to use many of his photographs; Simon Stoker; Anthony Foucar; Anita Mountain; Jean Melville; Alan Scott. While every attempt has been made to contact copyright holders, I would like to extend my apologies if any individual or organisation has been overlooked and welcome any information or further contact (via my publishers) in regard to those responsible.

Many whose families were in Burma have shared photographs, documents and memories. In particular I would like to thank John Bostock who lent me photographs and documents; Les Halpin for giving me his fathers account; Elephant Bills niece Di Clarke who gave me many contacts; Pamela Backhouse for allowing me to quote from her mothers papers; Yolande Rodda; and Diana Millington who also gave me much advice about the country today. Thanks are also due to the many people with whom I have corresponded via email, among them Patricia Herbert, Ron Findlay, Mark Steevens, Carol Horne, Ian Bootland, Nick Eades, Chris Eldon-Lee, and experts from the Oxford Centre for Refugee Studies for opinions, contacts and memories. I would also like to thank Jerry Quinn, Piers Storie-Pugh, Philippa Crockett of Raleigh International and Andrew Francis from UNHCR. Thanks are also due to my excellent guides in Burma. Finally I would like to thank my commissioning editor Jo de Vries, for sharing my enthusiasm for this story and the Forgotten War in general.

Preface

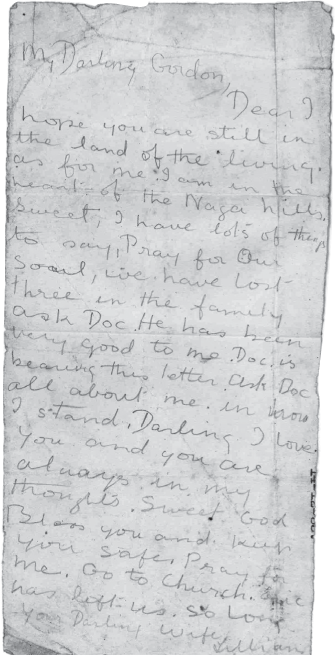

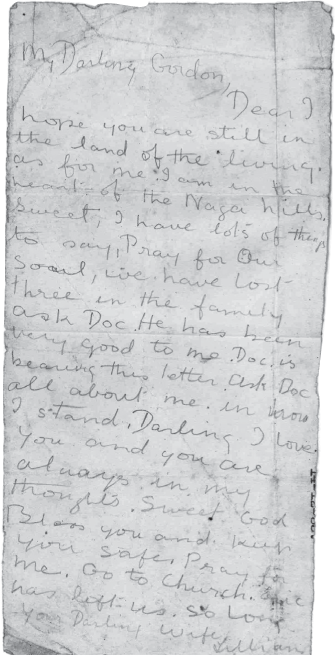

A torn scrap of paper, the size of a shopping list, is one of the few relics to survive from an incredible journey made 75 years ago. There are 104 words written on it in pencil. The handwriting slopes down to the right, the address is written on the bottom and folded over, and the paper is slightly stained, but intact. It is a love letter from Lillian Mellalieu to her husband Gordon, a lance corporal in the British Army.

Lillian had walked over 300 miles across some of the harshest terrain in the world to escape from the Imperial Japanese Army. All those caught up in the war in the Far East knew of their fearsome reputation. Women could expect to be raped and disembowelled, soldiers from the land of the rising sun did not believe in taking prisoners. In 1942, as the Japanese swept up through Burma, civilians fled into the jungle while the British Army fought soldiers considered amongst the best in the world, and lost. What the army did achieve, was to delay the enemy until the monsoon arrived. On 12 May the rain turned Burma into a vast paddy field; it forced the Japanese to abandon their pursuit of the army and consolidate their occupation of the land; it turned the escape of both army and civilians into a nightmare. Many of the refugees running from the enemy did not reach the safety of India for months. They clawed their way up steep mountainsides, through mud which sucked at their struggling feet, while they also battled starvation and disease. Lillian Mellalieu was one of those refugees.

Lillians story began just before Christmas 1941. She and her two sisters, Ethel and Irene, were brought up at No. 2 Dalhousie Street, Moulmein, with their brother Eric. Moulmein lies 120 miles east from Rangoon, across the Gulf of Martaban, and then, as now, was a town famous for painted paper umbrellas. After the invasion of Burma, the entire family fled north with the Japanese Army close behind them. A thousand miles from home, deep in the Naga Hills between Burma and India, exhausted and starving, Lillian rummaged for a scrap of paper among her belongings. She found the remains of a piece of foolscap. On one side was a list of precious possessions: a silver bowl and tray. These treasures may have begun the journey wrapped in her bundle, but by this stage any non-essential items had been discarded. Lillian sat down to write the note to her husband:

My Darling Gordon,

Dear I hope you are still in the land of the living. As for me. I am in the heart of the Naga hills. Sweet I have lots of things to say, Pray for Our Soul, we have lost three in the family ask Doc. He has been very good to me. Doc is bearing this letter. Ask Doc all about me. In how I stand, Darling I love you and you are always in my thoughts. Sweet God Bless you and keep you safe. Pray for me. Go to Church. Eric has left us.