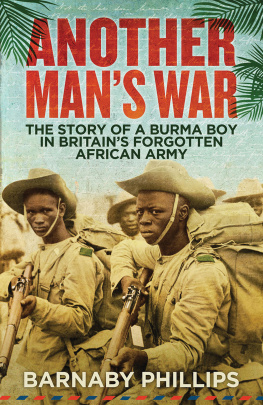

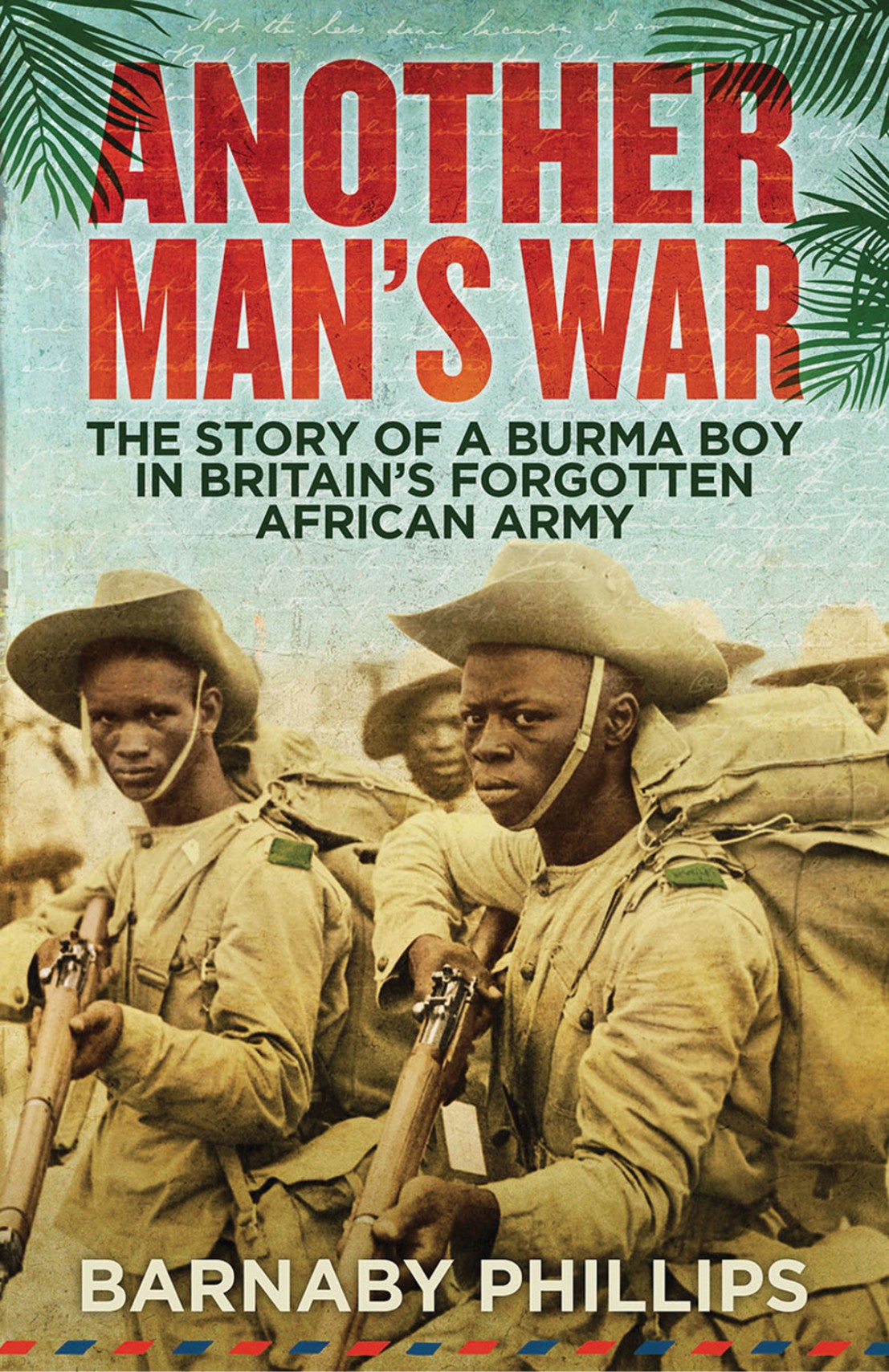

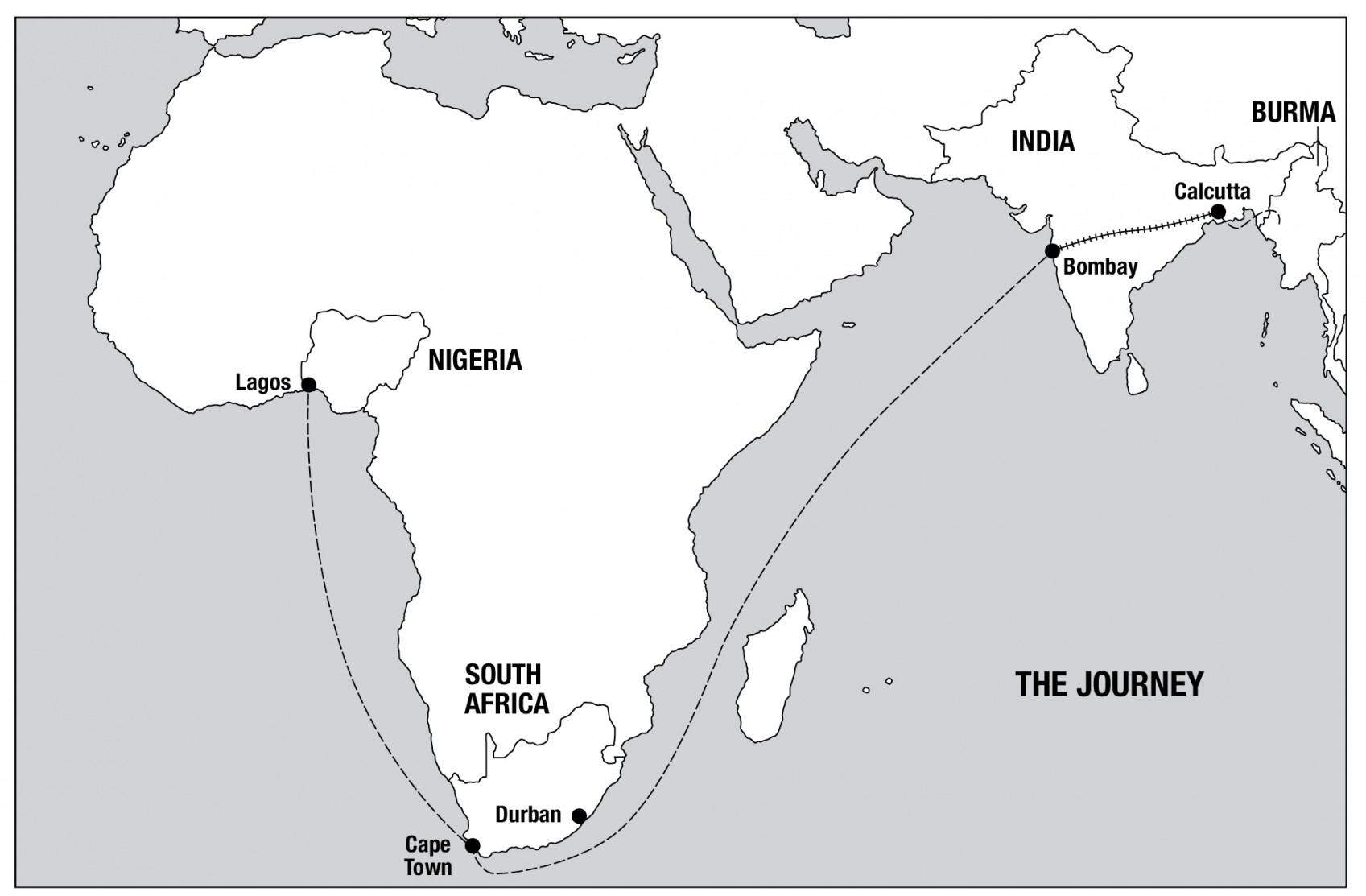

Two young West African soldiers shipped halfway across the world in 1943 to fight for the British in Burma find themselves abandoned wounded, starving and sick in the unmapped jungle of the Arakan. Their astonishing adventures are reconstructed here in gripping detail A real-life thriller with sobering implications for the British reader but I found it impossible to put down.

Hilary Spurling

author of Burying the Bones

Barnaby Phillips has uncovered a tale which touches the world in every sense. The story is a deceptively simple one, of a lanky boy who runs away from his dusty Nigerian village to join the British Army and is left for dead thousands of miles from home in the Burmese jungle. The miraculous sheltering and survival of Isaac Fadoyebo not only make an irresistible human drama. They also illustrate the terrifying global swirl of the conflict. Told with warmth and colour, this account of a forgotten soldier in a forgotten army in a forgotten war will not itself be easily forgotten.

Ferdinand Mount

author of The New Few

A Oneworld Book

This eBook edition published by Oneworld Publications, 2014

First published in North America, Great Britain & Australia by Oneworld Publications, 2014

Copyright Barnaby Phillips 2014

The moral right of Barnaby Phillips to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved

Copyright under Berne Convention

A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78074-522-0

Ebook ISBN 978-1-78074-523-7

Note on the Text

In 1989, Burmas military government changed the name of the country to Myanmar, and at the same time the capital Rangoon became Yangon. I have used the original names throughout this book, for the sake of consistency, as the greater part of it concerns the years around the Second World War. No offence is intended.

Typesetting and eBook design by Tetragon, London

Map artwork copyright by Critiqua

Oneworld Publications

10 Bloomsbury Street, London WC1B 3SR, England

Prologue

2 March 1944

Burma

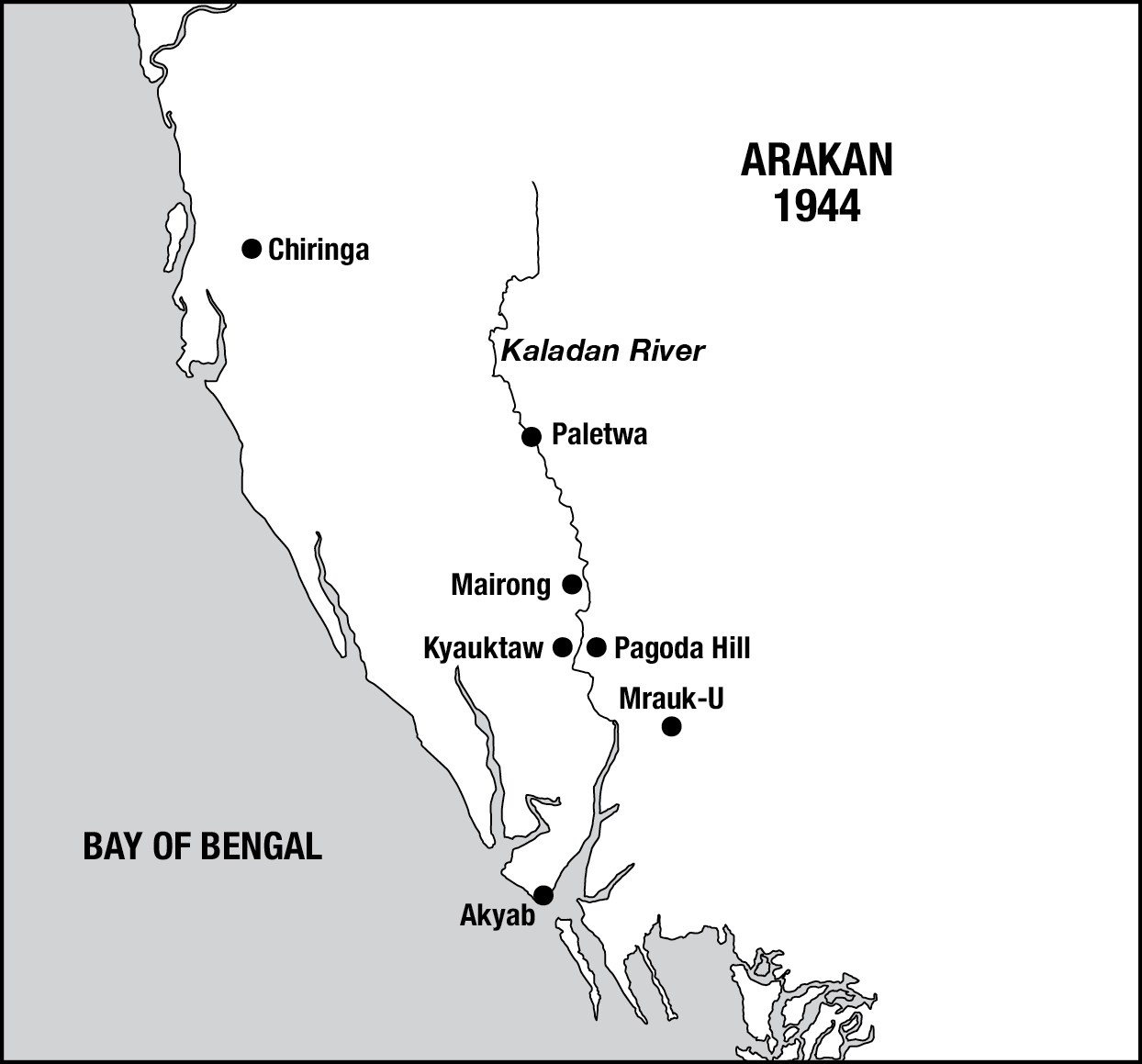

Isaac Fadoyebo would always remember the Kaladan as a wide and calm river, as silent as a graveyard. They had been drifting down it for four days. Trees lined the banks and monkeys played in the branches that reached above them. They were some ninety soldiers, British officers and their West African men, equipment heaped precariously high on the little fleet of bamboo rafts. Most of the West Africans could not swim. When Lance Corporal Felix Okoro fell in a couple of days previously, he had drowned. His body had washed up on the far bank the following morning, and, by the time the burial party reached him, vultures had already started to tear away at the flesh. It had been a horrible accident, Isaac thought, although not one that had created a feeling of impending disaster. He had woken that morning with no sense of foreboding. He didnt know that, for the rest of his long life, he would always think in terms of before and after this day.

The officers and men were taking breakfast together around a campfire. A simple affair of bread and tea, washed down with plenty of sugar, but no milk. This would be their last day on the river. That afternoon they hoped to arrive at the town of Kyauktaw, which the 81st Division had captured only the week before. They were a medical unit, trying to keep up with the advance. At Kyauktaw, theyd been told, they would be setting up a small field hospital for the division, because the Japanese were expected to put up more of a fight to the south. There would be casualties, and they would be responsible for them.

None of the men on the riverbank that morning could have been described as battle-hardened. The officers were doctors, almost all from Scotland. They were volunteers, and most had only signed up after war was declared. The West Africans were from Nigeria and Sierra Leone, and had joined the Army in the last couple of years. Theyd been trained in first aid and nursing, but given only the most rudimentary of fighting skills. The few that carried guns probably hoped theyd never have to use them. Their units name precisely determined their role in the great British Armys attempt to recapture Burma: they were the 29th Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), and they belonged to the 6th West African Brigade, part of the 81st Division of the Royal West African Frontier Force.

It sounded grand, put like that, but the truth was that the 29th CCS was an odd assortment of men of variable quality. When theyd crossed the border from India, theyd heard artillery, and seen British planes strafing enemy positions on distant hills. On one occasion, theyd even treated some injured Japanese soldiers who had been captured by the frontline soldiers. But that was weeks ago now. There were some whod begun to hope quietly that the Japanese had pulled out of the Kaladan Valley altogether.

The men dawdled. Most were wearing only vests and shorts. Many were barefoot. If they were going to spend another day back on the rafts, they asked, why bother to put boots on? Some ambled down to the water, to wash their faces. Others wandered off in the direction of the nearby village, a line of bamboo and thatch huts strung along the riverbank. When theyd arrived the previous evening, they were relieved to see that it was an Indian settlement. Indians , thats what they called the Muslims, because thats what they looked like. They could be trusted; the officers had drummed this into the men before theyd set out, and it was turning out to be true. It was the others, the Arakanese Buddhists, or Burmese as they called them, who were slippery. Why, they even looked Japanese. The Africans asked the Muslims what name they gave to their village. Mairong, they replied.

The commanding officer, Major Robert Murphy, looked at his watch. Half-past seven, time to load up the rafts. The mist over the river had burnt away, revealing the outline of the trees on the far side. He wondered if he should tell the men to make less noise. He didnt like this complacency. Looking down the sloping muddy bank, he saw Isaac sipping his tea and chatting to Company Sergeant Major Archibong Bassey Duke, a fellow Nigerian. There are two young men who seem to be enjoying this adventure, thought the Major.

That morning, Bassey Duke was warming to one of his favourite themes: life after the war. When it was all over, he told Isaac, theyd return home with some money to spend, and some stories to tell. Bassey Duke was a giant of a man. He wore blue shorts and a white vest, and would have been easily visible from the far side of the river. It was the end of the dry season, so the opposite bank was only a hundred or so yards away. Behind it, the sun was rising over the steep hills, the dark jungle still in shadow.