Contents

The 1945 Burma Campaign

and the Transformation of

the British Indian Army

MODERN WAR STUDIES

William Thomas Allison

General Editor

Raymond Callahan

Jacob W. Kipp

Allan R. Millett

Carol Reardon

David R. Stone

Jacqueline E. Whitt

James H. Willbanks

Series Editors

Theodore A. Wilson

General Editor Emeritus

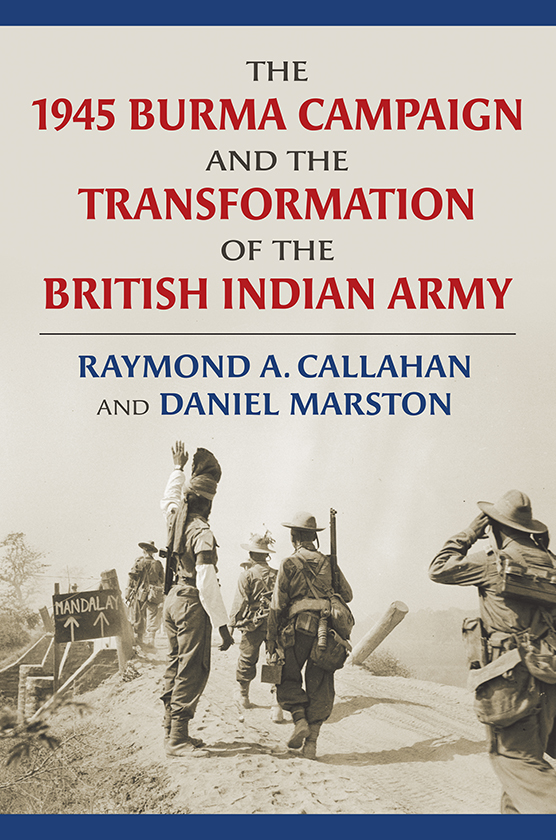

The 1945 Burma Campaign

and the Transformation of

the British Indian Army

Raymond A. Callahan and

Daniel Marston

University Press of Kansas

2020 by the University Press of Kansas

All rights reserved

All art courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, unless otherwise noted.

Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66045 ), which was organized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State University, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Callahan, Raymond A., author. | Marston, Daniel, author.

Title: The 1945 Burma Campaign and the transformation of the British Indian Army / Raymond A. Callahan and Daniel Marston.

Description: Lawrence : University Press of Kansas, [ 2021 ] | Series: Modern war studies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020018384

ISBN 9780700630417 (cloth)

ISBN 97807 00630424 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: World War, 1939 1945 CampaignsBurma. | India.

ArmyHistoryWorld War, 1945 . | Great Britain. Army. Army, XIV. | World War, 1939 1945 Japan. | World War, 1945 Great Britain. | World War, 1939 1945 India.

Classification: LCC D..C 2021 | DDC ./ 2591 dc

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/ 2020018384 .

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

Printed in the United States of America

The paper used in the print publication is recycled and contains percent postconsumer waste. It is acid free and meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z. 1992 .

To my daughter Sarah, for her never failing supportand with thanks to Dan who invited me to join in writing this book.

To Nancy and Bronwen who the make the journey worthwhileand to Ray who shared the idea and the endeavor. Finally, to all my AoW/STP alumni who have made me a better historian.

Contents

Preface

In December 1944 , the commander of the British XIV Army, Lt. Gen. Sir William Slim, revisited a site on the east bank of the river Chindwin recently cleared of the Japanese by his advancing army. Schwegyin was the place where, in May 1942 , Slim, then an acting lieutenant general commanding the hastily improvised Burma Corps (Burcorps), had destroyed its remaining wheeled and tracked vehicles, as well as its artillery pieces, which he lacked the means of getting across the Chindwin. It was the last act in the long retreat of Burcorpsthe longest in British military history, in fact. As Slim walked among the rusting wreckage of Burcorpss equipment he reflected on the transformation that had occurred in the two and a half years since that dark May: Some of what we owed we had paid back. Now we were going to pay back the restwith interest. This book is the story of that payback.

Of course, the forgotten XIV Army of World War II has subsequently received considerable attention, scholarly and popular, and Slim, little known in 1944 , is now regarded as one of Britains finest generals. But there are aspects of the final act in the longest land campaign that Britain (or the United States) would fight in World War II that make it worthy of further attention.

There is Slims remarkable careerthe lower-middle-class boy who became an officer only because the First World War opened the door for him to become a temporary gentleman. The unfashionable Indian Army allowed him to transform himself into a regular after 1918 .

After leading Burcorps out of Burma in 1942 , he played a crucial role in the remarkable military renaissance that transformed the Indian Army and then, with that reborn army, won two defensive battles in 1944 that fatally damaged the Imperial Japanese Army in Burma. In his campaign of 1945 , the most brilliant feat of operational maneuver by any British general in World War II, he reconquered Burma, shredding his Japanese opponents. Then, in the moment of victory (won by an overwhelmingly Indian British XIV Army, whose African component outnumbered its British), he was sacked by his British Army superior, whom, in the aftermath, Slim replaced.

Behind this dramatic story was another. The war marked the effective end of the Rajwhat happened in the last two years of its existence was, fundamentally, a protracted argument on when to vacate the premises and whom to hand the keys to. The end of the British Raj in India, entailing, as it did, the speedy demise of British Asia, is one of the central facts of twentieth-century history. This great transformation was, of course, brought about by many factors but not the least of them was the Indianization of the Indian Armys officer corps under the pressure of war. As Slims great victory signposted the change from the army Kipling knew to a modern army with a growing number of Indian officers, the praetorian guard of the Raj evaporated. Every Indian officer worth his salt is a nationalist, the Indian Armys commander-in-chief, Claude Auchinleck, said as the XIV Army took Rangoon. That was a sign that the curtain was coming down on the Raj.

The Burma campaign may not have contributed in a major fashion to the final defeat of Japanas a recent popular historian has pointed outbut was of first-rate importance in the transformation of South Asia, as well as underlining the continuing importance of inspired leadership in complex human endeavors.

The 1945 Burma Campaign

and the Transformation of

the British Indian Army

Introduction

Early on January 1942 , Japanese forces advancing from recently occupied Siam (Thailand) clashed with a company of the / th Gurkha Rifles, deployed near the Burmese frontier with Siam some fifty miles east of Moulmein. It was the opening encounter in a very long war that ended only with Japans surrender, forty-four months later. There was little air cover. The th Indian was forced steadily back until, at the Sittang River (the last barrier before Rangoon and its vital port), aggressive Japanese tactics, the growing weariness and disorganization of the division (the RAF, making a rare appearance, had bombed them), and their commanders debility produced catastrophe. The bridge over the Sittang was blown with two-thirds of the division on the wrong side. In the aftermath, the th Indian mustered less than a brigadeand only half of the survivors had rifles. The road to Rangoon was open and once Rangoon fell there was no possibility of holding Burma, even if enough trained troops and air support were availableand neither was. It was now a matter of whether the remnants of Burmas defenders could be successfully withdrawn to India (with which Burma had neither road nor rail connections). Into this gloomy picture two new commanders were introduced. The commander-in-chief, India, responsible for Burma, descended upon the scene and sacked the commander of the th Indian (he was subsequently reduced in rank and compulsorily retired). In his place, the assistant division commander, D. C. T. Punch Cowan, took over the etiolated division. He would command it, brilliantly, for the rest of the war. Even more important, to bring more coherence to the forces in Burma (in addition to the th Indian, there was the st Burma Division, most of whose Burmese troops had already deserted) a small corps headquarters (Burcorps) was created, without much of the equipment and personnel such a headquarters usually had. To command it Maj. Gen. William Slim, bumped up to acting lieutenant general, was brought from Iraq, where he had successfully commanded the th Indian Infantry Division. Slim took over on March 1942 . Over the next two months he would lead Burcorps, attenuated but intact, out of Burma and into the bordering Indian province of Assam. He was assisted by Cowans success in breathing life into what remained of the th Indian and by the British th Armoured Brigade (landed just before Rangoon fell). With their long experience of the desert war against Rommel, the th brought not only a veteran presence, but firepower and a signals net that Burcorps desperately needed. But most of all, what got Burcorps back to India was Slim. He had taken over in the midst of disaster and Burcorps would several times teeter on the edge of further disaster as it trekked toward Assam and safety. Slims determination, his refusal to panic, his tactical skill, and that intangible quality that already clung to him like a cloak and that we call leadership brought it through. Slim learned a lot on that long retreat and he formed a resolve to use that knowledge to expunge the debacles and defeats of 1942 with a victory that would recover all that had been lost.