First published in Great Britain in 1969 by

Martin Seeker & Warburg Limited

Reprinted in this format in 2017 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street, Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright The Estate of Ronald Millar, 2017

ISBN 978 1 47389 200 2

The right of Ronald Millar to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The Publishers have made every effort to trace the author, his estate and his agent without success and they would be interested to hear from anyone who is able to provide them with this information.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Printed and bound in England

By CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword Aviation, Pen & Sword Family History, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Pen & Sword Discovery, Pen & Sword Politics, Pen & Sword Atlas, Pen & Sword Archaeology, Wharncliffe Local History, Leo Cooper, Wharncliffe True Crime, Wharncliffe Transport, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics, The Praetorian Press, Claymore Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Frontline Publishing

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

All illustrations are contemporary The author and publishers would like to thank the Imperial War Museum for permission to use .

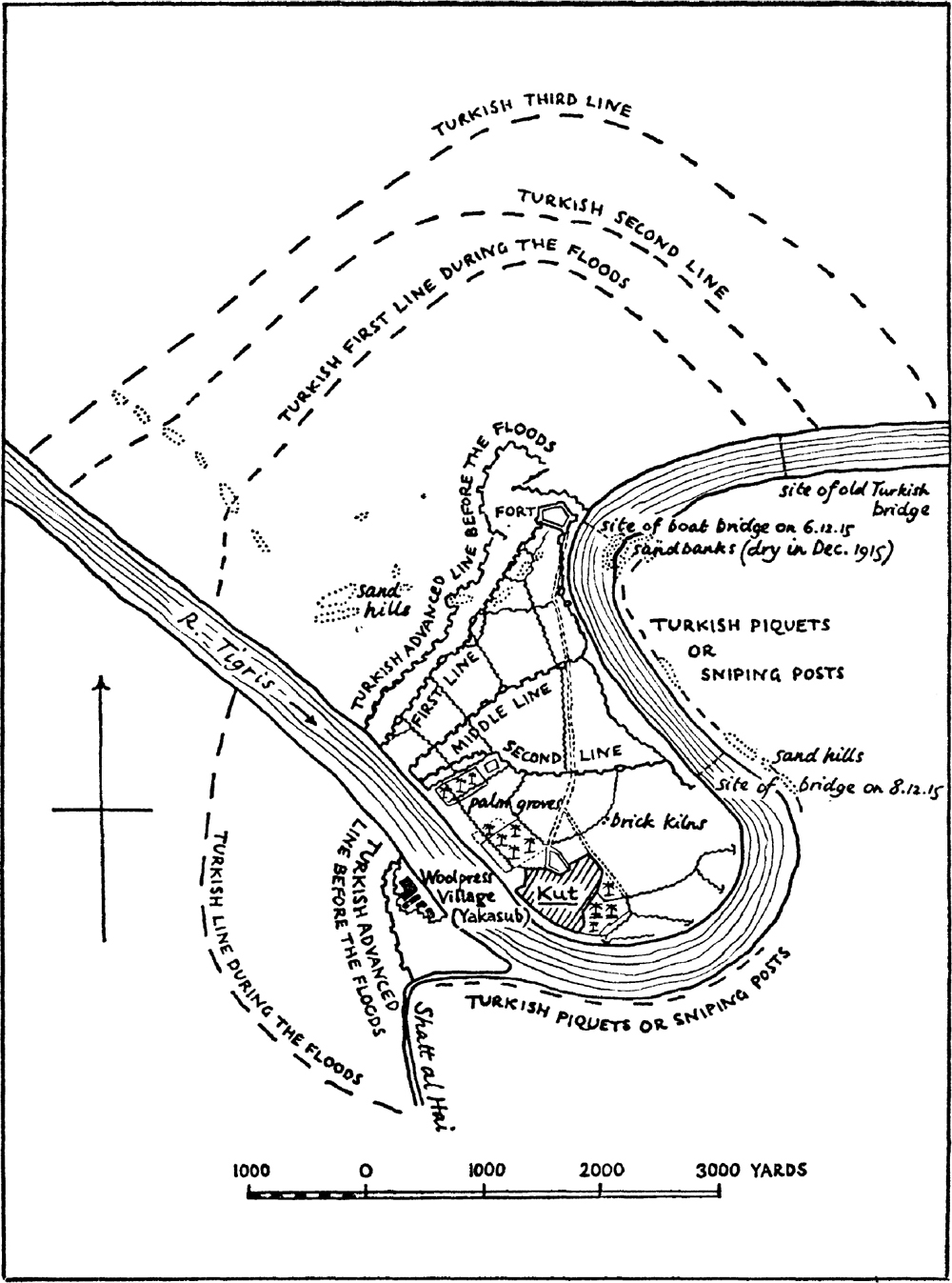

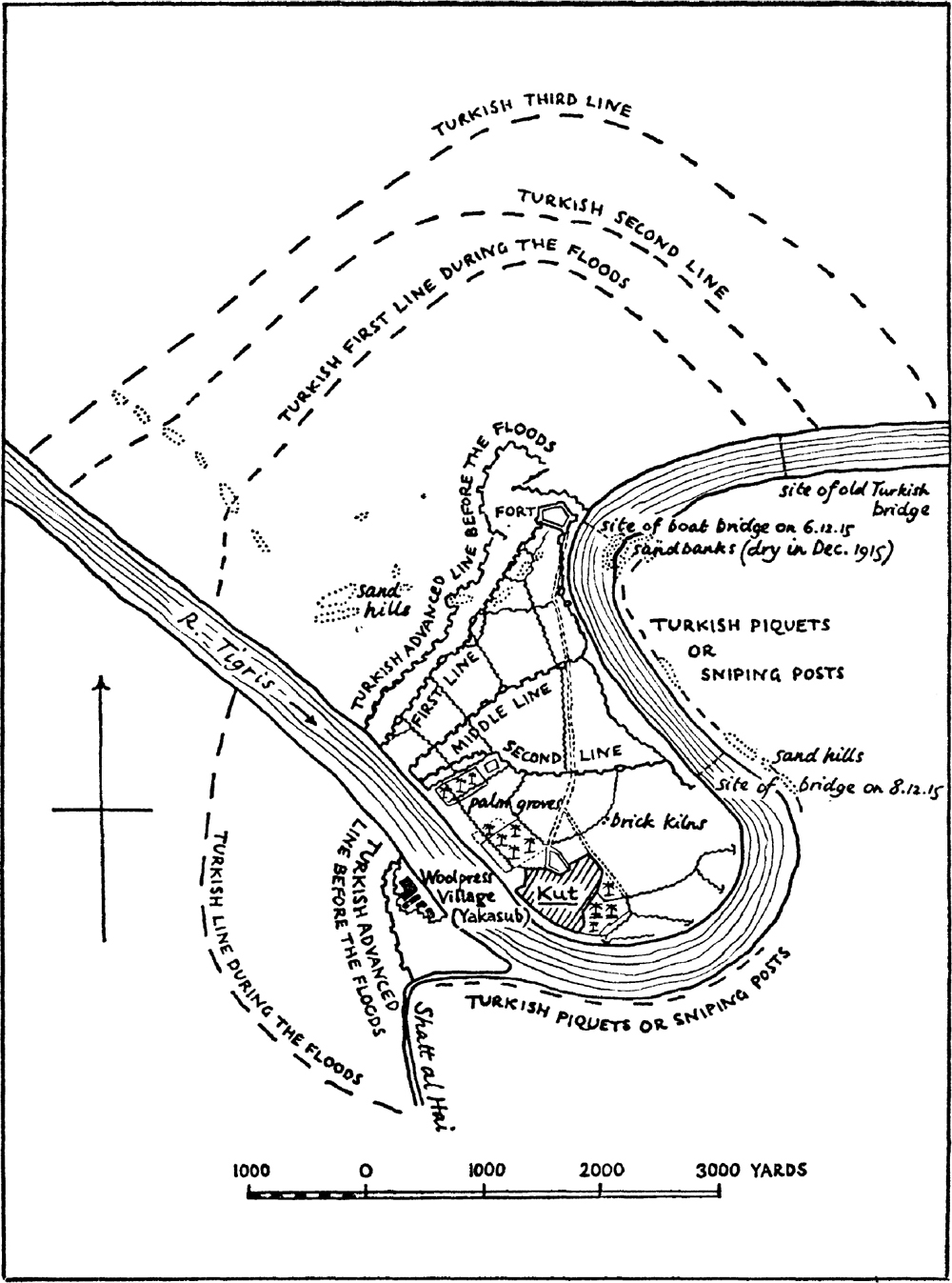

MAPS

No man goes as far as he who knows not whither he goes.

Oliver Cromwell

I

THE ROAD TO NOWHERE

It was late in the afternoon of one day in mid-May 1916. The remains of the Palace and Audience Hall of Chosros 1, plundered and destroyed by the Arabs under Omah 300 years before, reared high above the parched, brown country on the left bank of the Tigris.

Ctesiphon was no stranger to violence and bloodshed. For centuries it had been the battlefield of the Middle East. Assyrians, Persians, Greeks, Arabs and Justinians Romans had fought and died at this tumulus-bubbled and desolate spot. Now the brazen sun of Mesopotamia was once more to be the accomplice in the death of another army. Approaching the white-stone ruins was a long, straggling column of some 2,000 British soldiers. Some still wore the remains of khaki drill tropical uniform; others were almost naked. They had stumbled and staggered for nearly fifteen miles that day without water or food. The suffocating heat had reduced the men to the point where brains were numb and eyes had taken on the blank stare of the hopeless. The wake of the column was strewn with human litter, the dead, the dying and others, unable to march any further, waiting for death from the rifle-butts of their Arab guards.

These Kurdish guards had gone on the rampage soon after the troops had marched out of the temporary Turkish prisoner-of-war camp at Shumran, now some eighty miles behind. At first they had stolen the prisoners food rations, then their water-bottles and even their boots. Those who had managed to retain their footwear had tried to help their less fortunate comrades whose blood- and dirt-caked feet had refused to carry them any further, but it had been too much. Now those who fell behind were never seen again. Earlier these men had fought back at the savagery of their guards but now almost senseless with sun-stroke and exhaustion they were resigned to their fate. Some were even impatient for death and an end to their misery.

A party of British officer prisoners-of-war, separated from their men at Shumran a week before and now being taken upstream by steamer, saw just a part of the tragedy. The men were frequently attacked by the mounted guards for no discernible reason. As the column drew near the halted steamer the blistered faces of the men could be clearly seen. As they straggled by they held their hands out hopelessly to the officers. Some fell and were beaten with cudgels and by what appeared to be whips. Many were desperately ill with cholera and a green ooze issued from their lips. One private chose death in his own time. He halted and fumbled inside the remains of his tunic for a cigarette end. Lighting it, he drew deeply, and then with his arms about his head as if to shield the hateful column from sight, he threw himself face downwards in the hot dust. He puffed steadily as the first rifle blow struck his body then the cigarette, still smouldering, rolled from him. Where the man had obtained the cigarette was difficult for the officers to guess, for all tobacco had been exhausted many weeks before. It was thought that the man must have been saving the cigarette for a special occasion.

Thus the pitiful trail into captivity spread its dry bones from Shumran, through Aziziya, Baghdad, Tikrit, Mosul, Nisibin, Ras al Ain, Mamourra and Aran. The ambassador of the then neutral United States of America, Mr. Bissell and his countrys consuls in many parts of the Turkish Empire, saw the results of the terrible march and protested with all the means at their disposal. In a number of cases they were able to ease the plight of the British and Indian troops. In others they could do nothing. Some of the troops survived; the majority marched on for ever.

At the end of the war a British parliamentary report deplored what it described as the indifference and apathy of the Turkish authorities. But the events that led up to this tragic affair clearly displayed that the Ottomans did not have the sole monopoly of these shortcomings. Just six months before these men of the 6th Poona Division had been considered invincible. British newspapers had feted their victories and there had been many. But they had been urged on to reap the harvest of too much optimism and too little foresight. Baghdad by Christmas had been the call. The strategy had almost succeeded but the advance, like so many others down the centuries, had foundered at Ctesiphon.

The Mesopotamian theatre of World War 1, dubbed a sideshow because it lacked the emphasis of the numbers of the Western Front, in actuality wanted for nothing in the way of calamity and horror. In fact it generated its own kind of nightmare.

The original expedition to Mesopotamia had quite modest objectives. For some years prior to the outbreak of war Great Britain had exercised a protectorate over the sheikdoms of Kuwait and Mohammera. This influence became vital as the British Navy began to rely increasingly on oil for its motive power as the junction of the pipeline which ran down from the Persian oilfields was on Aberdan Island in the Shatt al Arab at the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Britain had also purchased a controlling interest in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company which owned the pipeline. To protect the 150 miles of pipeline was beyond the resources of the British military at the time but it was considered that if Basra was captured this would encourage the Arabs in the area to throw off the cruel oppression of their Turkish masters and join the victors. This would be the first stone in an avalanche that would sweep the Turks out of Mesopotamia altogether.

Next page