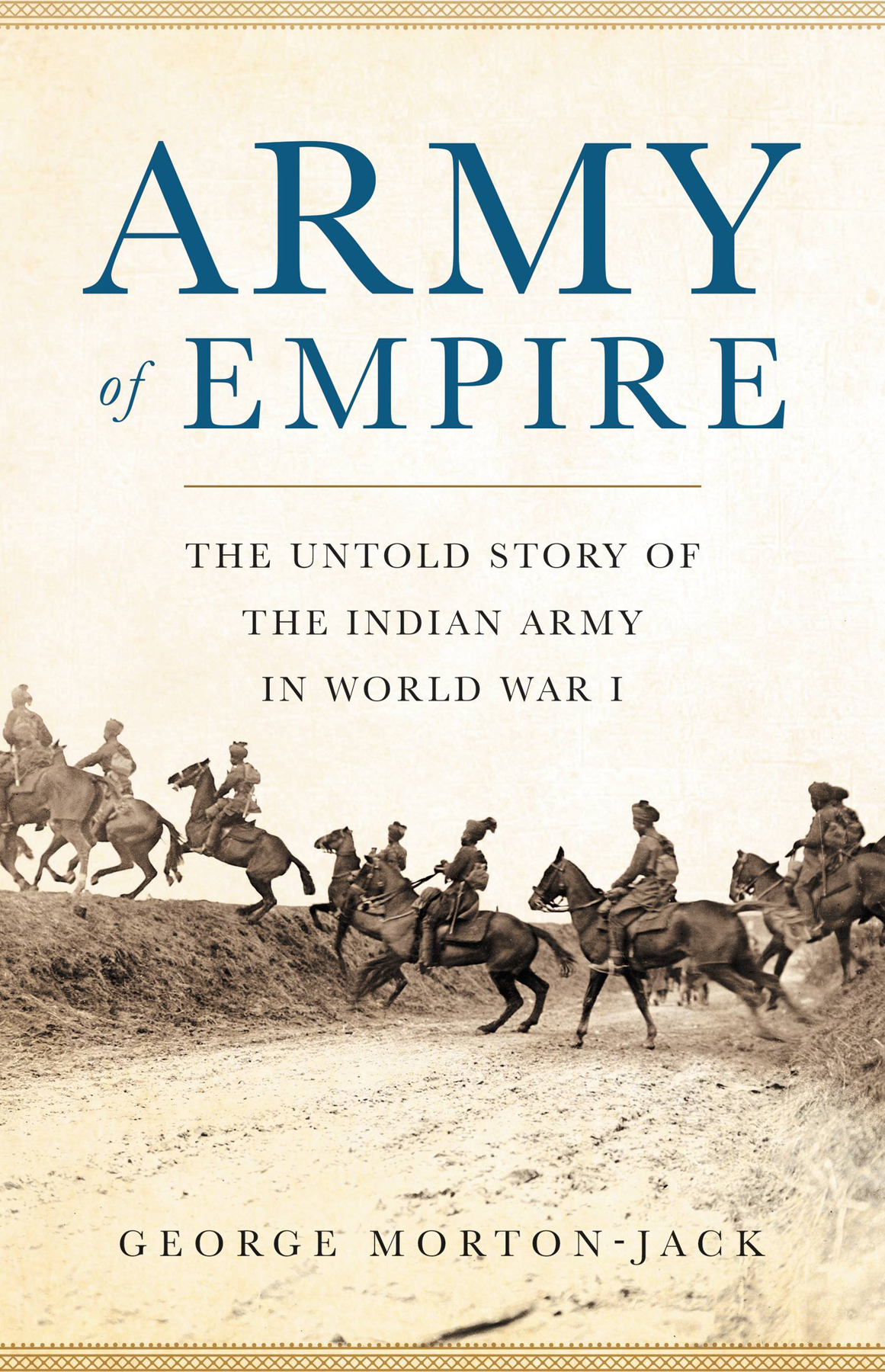

Cover image Indian cavalry in France, April 1917 IWM (Q 2062) Nisha_Images / Shutterstock.com

Cover 2018 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Originally published in Great Britain in hardcover and ebook by Little, Brown in September 2018

Published by Basic Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Basic Books name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

A splendid gathering

I n 1911, the Indian Empire put on its most dazzling ever display of pomp and pageantry to celebrate George Vs accession as its King-Emperor. He embarked on a public tour to show himself to the Indian people as their absolute ruler in the tradition of Akbar, Shah Jahan and the other Mughal emperors, and its climax was the Delhi Durbar in December at a vast purpose-built amphitheatre outside the city. Here 200,000 spectators, many of them sitting in stands arranged like flowerbeds according to the colour of their turbanssnow-white, orange, yellow or greensaw him make a spectacular entry in the winter sunshine as an authority second only to God.

To the thunder of artillery fire and flourishes of silver trumpets, George appeared in a horse-drawn maroon carriage in purple robes and a crown of 6100 diamonds, the Queen-Empress Mary at his side, and footmen in their wake with fans of peacock feathers and yak tails, and golden maces with king cobra heads. After processing to a throne under a red velvet canopy topped with a golden dome and small minarets, he presided over an afternoon of slick ceremonials in his honour. To kettle-drum rolls, claps and cheers, bowing maharajahs laid swords at his feet, and scroll-clutching civil servants read out proclamations of his semi-divine and supreme will, before the British national anthem rang out.

The spectators were mostly civilians, but standing in the middle of the amphitheatre, set among the red clay roads criss-crossing it, the empires professional Indian Army was on show: 15,000 of its men under their British officers, standing bolt-upright in immaculately turned out regimental blocks, from towering Sikhs, six-foot tall in their khaki breeches and tunics with turbans, brown leather belts and boots, down to Gurkhas, five-foot-five in green uniforms with their cowboy-style felt hats and Himalayan curved knife, the khukuri, alongside a smaller number of British Army troops in scarlet and blue with spotless white pith helmets.

Watching on from the King-Emperors cavalry escort was Thakur Amar Singh, an observant and quietly spoken Hindu officer in his early thirties, on a plumed horse with a snow leopard skin draped under his saddle. I wanted to see it thoroughly, he wrote enthusiastically in his diary of the amphitheatres great spectacle. Just as we entered the pace was reduced from a trot to a walk and we were able to see what a splendid gathering it was. For him, the Delhi Durbar was great & historic [and] will be remembered for ages worthy of the illustrious sovereign. Among the standing Indian soldiers, meanwhile, was a bearded Muslim soldier named Mir Dast. He had enlisted in 1894, been decorated for bravery in action in 1908, and in the amphitheatre joined the rest of the Indian troops in a flawless rifle fire salute that rippled from them to troops outside lining the road for several miles to the King-Emperors camp, and then back again. According to Mir Dasts British officer, he was just the kind of man British recruiters looked for: always outstanding and intensely imperialist.

With men like Mir Dast in its ranks, the British generals in the stands seemed to have every confidence in the Indian Army. There was the Chief of the Indian General Staffa Scotsman, Douglas Haigwho considered the Durbar a wonderful show. And sitting near him was the Indian Armys most senior field commander, James Willcocks, who also happened to be the British soldier most decorated for active service. The Durbar, Willcocks was sure, confirmed the Indian troops visible allegiance to their King-Emperor. It left its imprint deeper than any event that took place during my long service in India, he wrote. It was used by the Indians as the date to describe occurrences by, i.e. before or after the Durbar The King was the only power the Indians understood thoroughly he alone could finally say yea or nea.

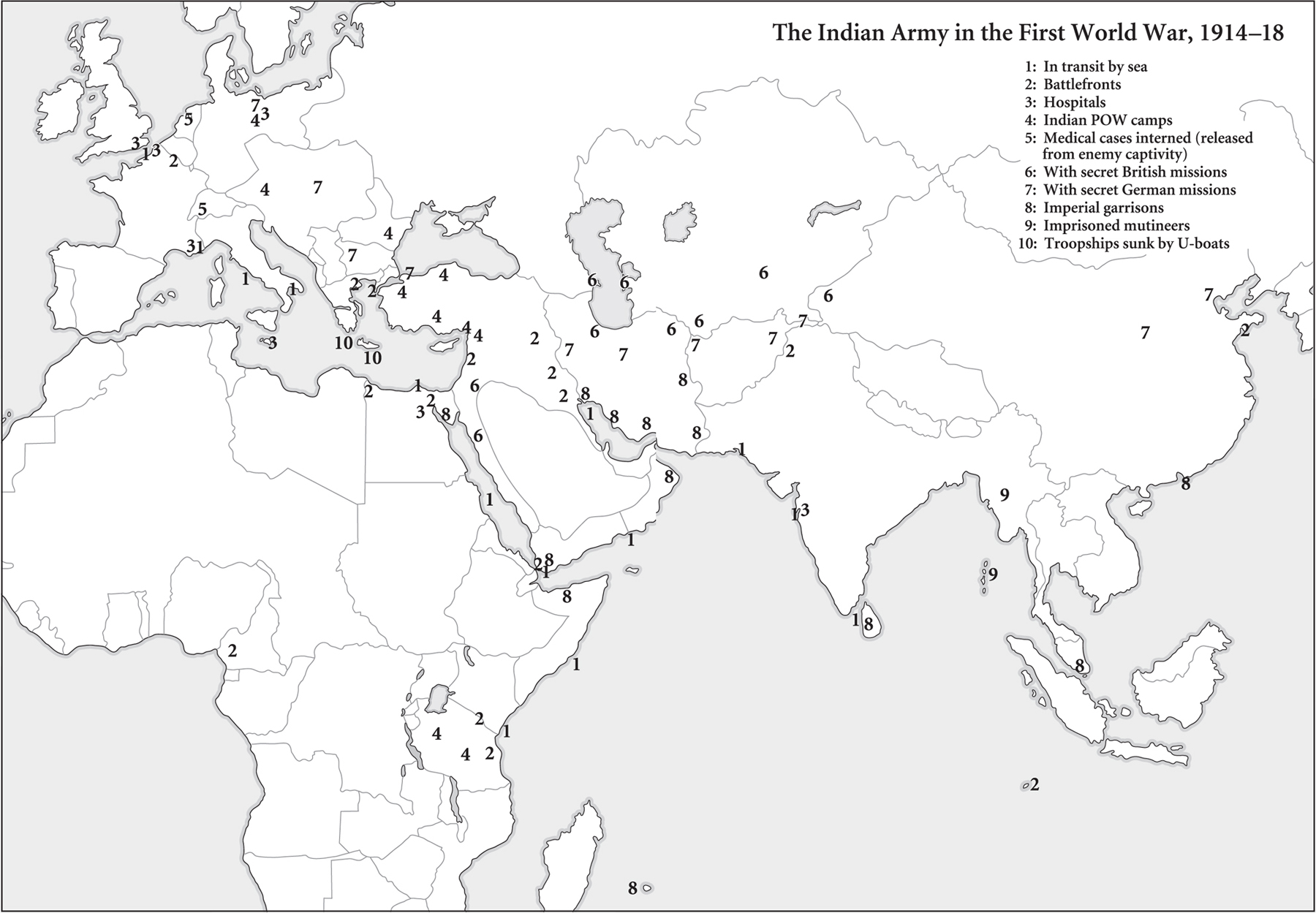

To all appearances, therefore, when the First World War broke out in 1914 the British, and by extension the Allies, had in the Indian Army a professional force ready, willing and able to fight for its King-Emperor. Up to 1918, a total of 1.5 million Indian recruits would serve in the Indian Army, seven times the prewar number. They were to fight far and wide, on Flanders fields, rocky ridges above Turkish beaches, coral island shores with swaying coconut trees, golden grasslands with roaming giraffe, lion and rhino, in steaming tropical rainforests on mountain slopes wandered by gorillas, and the sun-baked deserts of the Islamic world.

In fact, the Indian Army was the Allies most widespread army of 191418, serving in foreign lands across Africa, Asia and Europe that today number some fifty different countries. This book is the first single narrative of it on all fronts, a global epic not only of the Indians part in the Allied victory over the Central Powers, but also of soldiers personal discoveries on their four-year odyssey. It retraces Indian Army footsteps from front to front, following the Hindu diarist Thakur Amar Singh, the Muslim Mir Dast (who was to be one of eighteen Indian Army Victoria Cross winners), Douglas Haig, James Willcocks and others. In exploring the Indians war, this book reveals their differing experiences of the worldwide tragedy of 1914 to 1918, whether as villagers or travellers, fighting men or prisoners of war, secret agents or lovers across cultural divides. So far as possible, the story is told in the words of the Indian Armys officers and men, using wartime letters and veteran interviews, many previously unpublished, to revisit the First World War as never before.

The Indian Army

The Indian Army of 191418 was uniquely multicultural, combining such a variety of humankind into a single brotherhood-in-arms that it was really a modern wonder of the world. Its officers and men were a breathtaking array worshipping more gods and speaking more languages than any other army on the planet. They were a mix of Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians and pagans, and they spoke not just Hindustani, the armys official vernacular blending Hindi and Urdu, but also their separate home languages. These were numerous and some Indian servicemen not fluent in Hindustani could only understand each other if they knew the right language: Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, Pushtu, Dari, Bengali, Marathi, Tamil, Burmese, Nepali or a number of other tongues, uttered in local dialects beyond count.