JAPANS

BLITZKRIEG

By the same author

Masters Next to God

They Sank the Red Dragon

The Fighting Tramps

The Grey Widow Maker

Blood and Bushido

SOS Men Against the Sea

Salvo!

Attack and Sink

Dnitz and the Wolf Packs

Return of the Coffin Ships

Beware Raiders!

The Road to Russia

The Quiet Heroes

The Twilight of the U-boats

Beware the Grey Widow Maker

Death in the Doldrums

JAPANS

BLITZKRIEG

The Rout of Allied Forces

in the Far East 19412

by

Bernard Edwards

First published in Great Britain in 2006 by

Pen & Sword Maritime

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Bernard Edwards, 2006

ISBN 1 84415 442 4

978 1 84415 442 5

The right of Bernard Edwards to be identified as Author of this Work

has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or

transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical

including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and

retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in Sabon by

Phoenix Typesetting, Auldgirth, Dumfriesshire

Printed and bound in England by

Biddles Ltd., Kings Lynn

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the Imprints of Pen & Sword

Aviation, Pen & Sword Maritime, Pen & Sword Military, Wharncliffe

Local History, Pen & Sword Select, Pen & Sword Military Classics and

Leo Cooper.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

This is for my first ship, the dear old Clan Murdoch.

She sailed serenely through it all.

Painting her shapely shadows from the dawn

An image tumbled on a rose-swept bay,

A drowsy ship of some yet older day.

JAMES ELROY FLECKER

Contents

The author wishes to thank the following for their help in researching for this book:

Royal Naval Association, Swindon Branch; Instituut voor Maritieme Historie; US Naval Historical Center; National Archives, Kew; and Willem Hage, Albert Kelder, George Monk, Bernard De Neumann, Frits Norbergen and Ken Williams.

JAPANS

BLITZKRIEG

The evacuation of the remnants of the British Army from the beaches of Dunkirk in June 1940 has always been seen as snatching victory from the jaws of defeat. Britain then stood alone, and in the months that followed her cities suffered intense bombing, and the threat of invasion from across the Channel was ever imminent. Yet in the midst of all this adversity thoughts were turned towards the defence of the Empire in the East. On 11 August 1940, Winston Churchill wrote to the Prime Ministers of Australia and New Zealand:

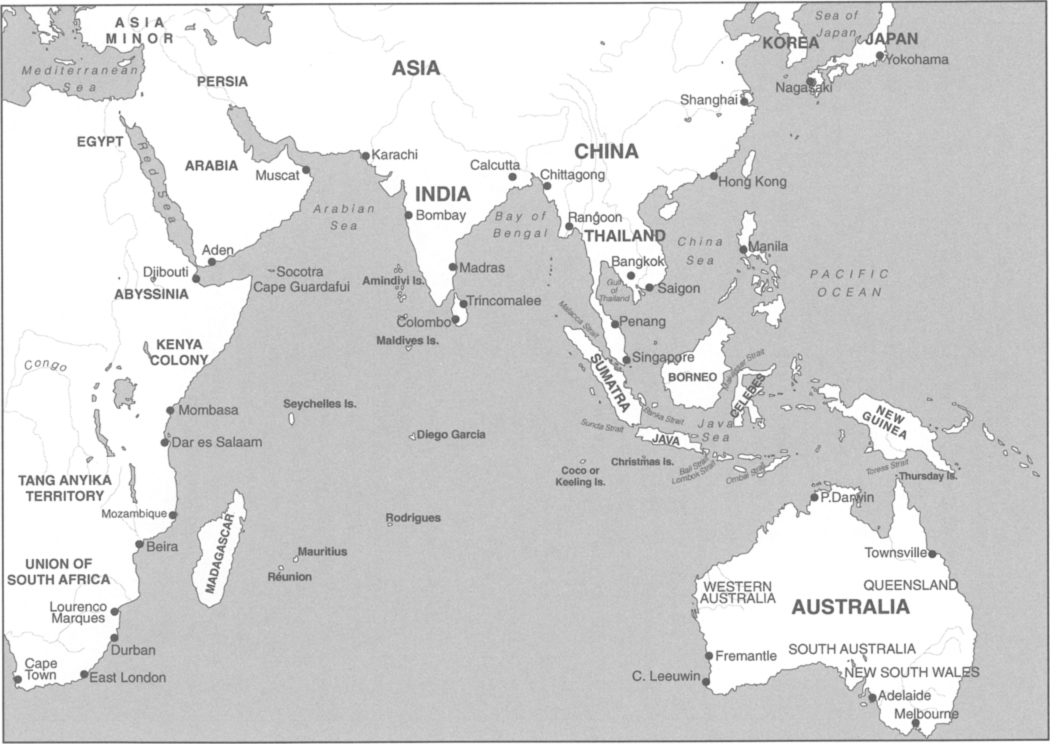

The combined Staffs are preparing a paper on the Pacific situation, but I venture to send you in advance a brief foreword. We are trying our best to avoid war with Japan I do not myself think that Japan will declare war unless Germany can make a successful invasion of Britain Should Japan nevertheless declare war on us her first objective outside the Yellow Sea would probably be the Dutch East Indies In the first phase of an Anglo-Japanese war we should of course defend Singapore, which if attacked which is unlikely ought to stand a long siege. We should also be able to base on Ceylon a battle-cruiser and a fast aircraft carrier, which, with all the Australian and New Zealand cruisers and destroyers, which would return to you, would act as a very powerful deterrent upon the hostile raiding cruisers

Churchills defiant words were characteristic of British thinking in those early days, but with regard to Singapore his optimism was unfounded. It had been said many years before the outbreak of war that the impregnable fortress of Singapore was a myth, and it was in reality a 60 million floating dock whose sole defence was six 15-inch naval guns pointing mutely out to sea. As for basing a powerful naval force on Ceylon, with the Royal Navy needing all its strength merely to keep open Britains vital sea lanes in the Atlantic, this was a fantasy that could in no way become reality.

The defence of the Eastern sphere was discussed at a meeting of the War Cabinet in Whitehall in late August 1940 with Ministers and Chiefs of Staff present. It was the opinion of the Chiefs of Staff that Britain was in no position to face war with Japan, and following the meeting a top-secret twenty-eight-page report on the true situation was compiled. A copy of this report was to be sent to the C-in-C Far East without delay, and by as secure a means as possible.

Monday, 11 November 1940. As the sun rose in the east, turning the gently undulating waters of the Indian Ocean from steel-grey to a rich blue, the memories came flooding back to Captain William Ewan; memories of that other war, ended twenty-two years ago this day. So many men had died, amongst them men with whom he had sailed and whom he had known so well. Shipmates. Now, here he was once again pacing the bridge of a merchantman, her distinctive company colours hidden under a coat of drab Admiralty grey. He stopped in his stride and turned to look aft, to where the long barrel of the recently fitted 4-inch gun another relic of that distant war dominated the poop deck. He wondered if this gun would ever be fired again in anger. Looking back on the events of the night just past, he concluded that this might well be so.

Captain Ewans command, the 7528-ton Automedon, was one of Alfred Holts prestigious Blue Funnel Line, a regular Far East trader. Built on the Tyne in 1922, she was too young to have seen that other war, but had given a lifetime of exemplary service on the road to the East, and looked set to go on for another twenty years or so. Like most British cargo liners of her day, she had no pretensions to luxury, but was solid and dependable, her double-reduction turbines, even after so many thousands of miles steamed, still turning out a consistent 14 knots. She was manned by British officers and Chinese ratings, a total complement of ninety-three, and had accommodation for twelve passengers, although on the current voyage only one of her cabins was occupied, by Mr Alan Ferguson and his wife, newly-weds on their way back to Singapore. In her holds, the Automedon carried a cargo of cased aircraft, vehicles, machinery spares, bicycles, microscopes, service uniforms, cameras, sewing machines, steel and copper sheets, whisky, beer, cigarettes, food supplies, and 120 bags of mail, a bizarre mlange of the necessities of war and peace.

The Automedons long outward passage, beginning in Liverpool in late September and taking her south to Freetown, around the Cape of Good Hope to Durban, and thence across the wide reaches of the Indian Ocean, had been uneventful. Once past Finisterre, the long lazy days at sea under untroubled blue skies, when the watches came and went by the bridge bell, and gins and tonics and steamer chairs at sunset signalled the end of another day, had lulled all on board into a false sense of security. The war was far away until, on the evening of 10 November, when the ship was forty-seven days out from Liverpool and approaching the north-western tip of the island of Sumatra, the idyll came to a sudden end.

Next page