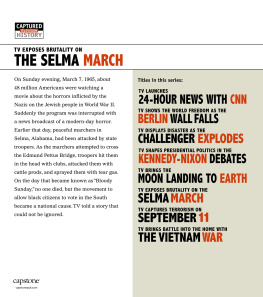

FOREWORD

Civil rights activists around the United States began sitting in protest at whites-only lunch counters in 1960.

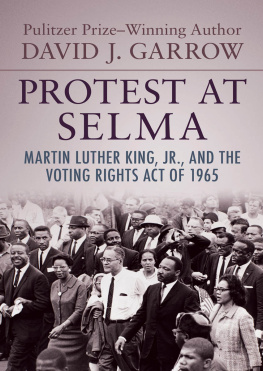

By 1965 the modern-day fight for the civil rights of African Americans was entering its 10th year. During that time, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), led by Martin Luther King Jr., had fought Southern institutional racism and discrimination. It had done so using nonviolent demonstrations, sit-ins, and marches. King found an unlikely but powerful ally in the new president, Lyndon Baines Johnson. Through their combined efforts, King and Johnson had gotten Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which made racial discrimination in employment and public facilities illegal.

But African Americans were still denied the right to vote in many parts of the South. Local and state governments made it extremely difficult for black citizens to register to vote. They gave unfair literacy tests that no oneblack or whitecould be expected to pass. They stopped black people from registering by threatening to tell prospective voters employers that they had registered. This threat told black people that they would lose their jobs for registering to vote. Without the vote, black citizens had no voice in who would represent them in local, state, and national government.

Selma, in Dallas County, Alabama, had a large black population, but only 156 of the 15,000 black adults who lived there were registered to vote. For this reason, in 1964, King chose Selma as a testing ground for voter registration demonstrations and protests. Over the next several months, both outside activists and local residents protested at the county courthouse on the issue of voter registration. Among the hundreds of demonstrators arrested on February 1 was King himself. While in jail, King wrote his stirring A Letter from a Selma, Alabama, Jail. The letter appeared in The New York Times on February 5, 1965, the day he was released on bail.

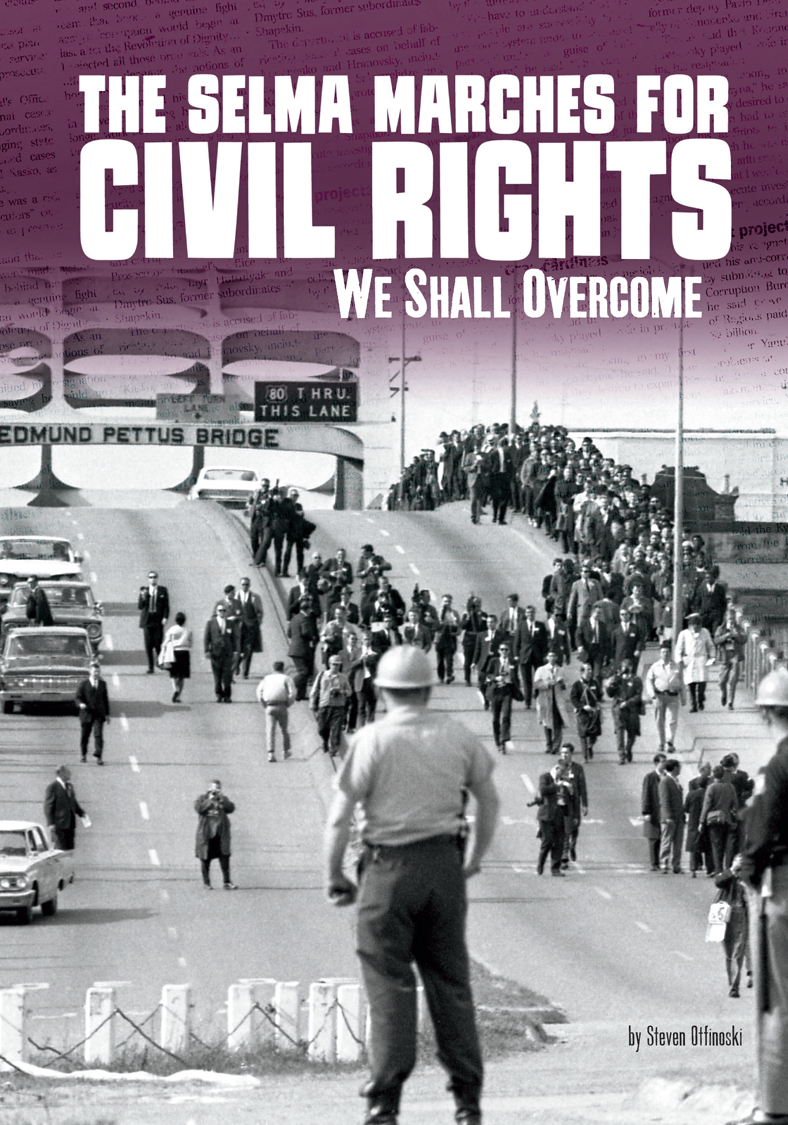

On February 28 a public meeting was held following the death of Jimmie Lee Jackson. Jackson, a black man, had marched in a peaceful protest in Marion, Alabama, on February 18. Alabama state troopers attacked the marchers and shot Jackson. He died eight days later. At the February 28 meeting, SCLC leader James Bevel suggested that King lead a march from Selma to Montgomery. Once in Montgomery, the capital of Alabama, King would directly confront Governor George Wallace about Jacksons death. King approved of the march, but he was worried about attacks on marchers by Alabama state troopers and white racists.

King left Selma on Friday, March 5, with his second-in-command, Ralph Abernathy. He planned to lead Sunday services in his home church in Atlanta, Georgia. Then he would return to Selma later on Sunday and lead the march.

Martin Luther King Jr. (left) along with fellow SCLC leaders Ralph Abernathy (center) and Andrew Young (right) led a voter registration effort for black citizens in Selma, Alabama, on March 1, 1965.

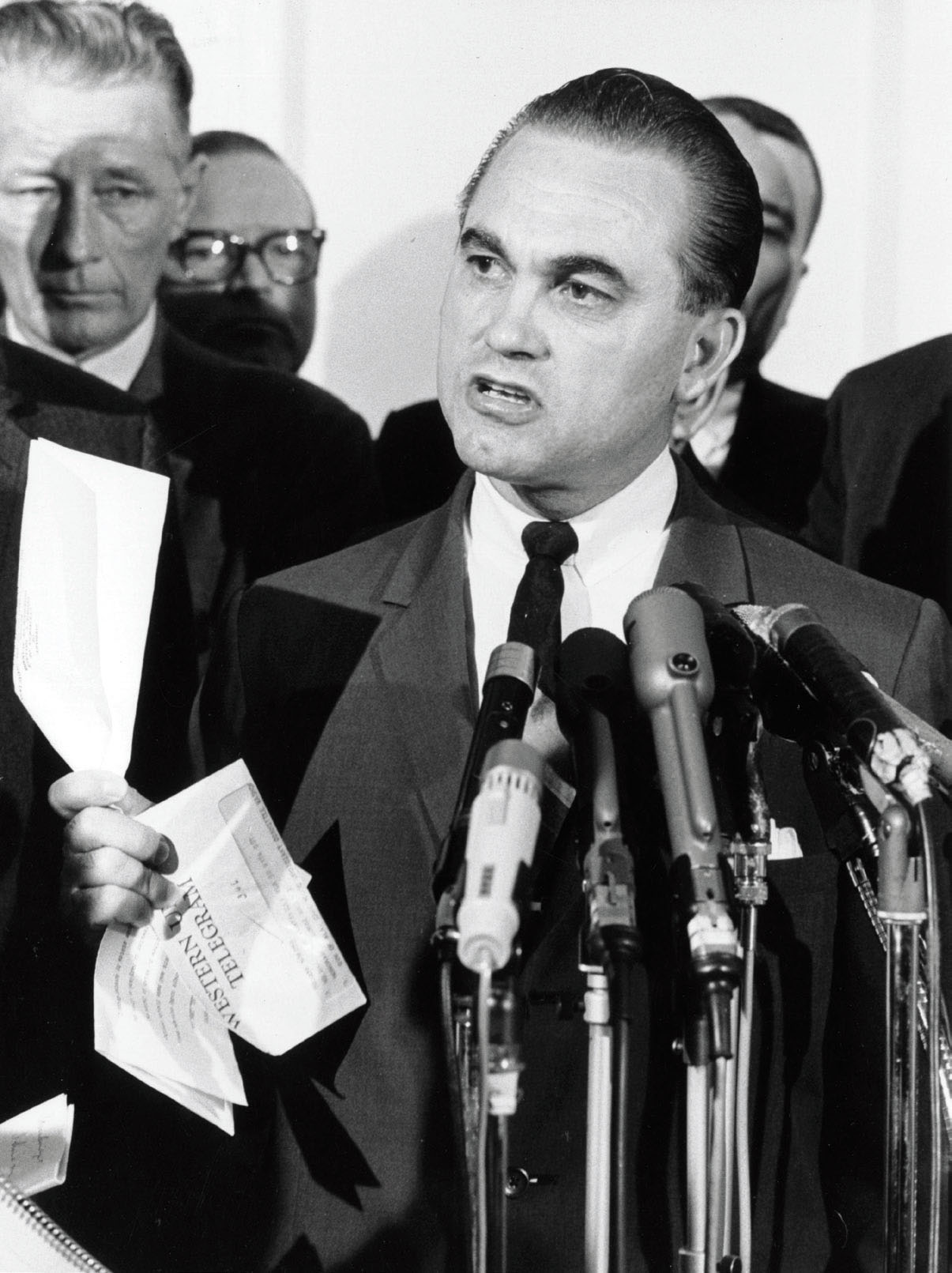

George Wallace

George Wallace

State Capitol, Montgomery, Alabama, March 6, 1965, 9:00 a.m.

Alabama Governor Martin Luther King Jr.s civil rights demonstrations in Selma. This had seriously challenged Wallaces authority.

Under Wallaces orders, men such as Dallas County Sheriff Jim Clark had responded to the civil rights activists. They had beaten demonstrators with clubs and sent electric shocks through them with cattle prods. But this had earned the governor unfavorable news headlines. Wallace didnt want more bad publicity if King followed through with his plan to march from Selma to Montgomery the next day. Yet he also wanted to stop the march and demonstrate his authority. He didnt know what to do.

Wallace called a press conference and tried to appear in control. The march, he told the gathered reporters, could not be tolerated. He explained that the march would interrupt the orderly flow of traffic and commerce on State Highway 80.

After the conference ended, Wallace pulled aside state trooper Colonel Al Lingo. Use whatever measures are necessary to prevent a march, he said.

A short time later Wallace spoke to Lingos lieutenant, Major John Cloud. He warned Cloud not to take any actions that would cause sensationalism. If they want to march, go beside them and protect them, Wallace said.

Cloud nodded, but the governor wondered what the troopers would do when the time came. He had a terrible feeling that events were still spinning out of his control.

Ralph Abernathy

West Hunter Baptist Church, Atlanta, Georgia, March 7, 1965, 9:45 a.m.

The Reverend Abernathy was preparing for Sunday morning services when the phone rang. It was Hosea Williams, another SCLC leader in Selma. After hearing Wallaces press conference warning, King and Abernathy had decided to postpone the march. But Williams felt the moment for the march was right. He said that the civil rights activists who had come to Selma to demonstrateboth black and whitewere ready. He requested that Abernathy ask King for permission to go ahead with the march to Montgomery in Kings absence.

Abernathy didnt care much for Williams. He thought Williams was too eager for a fight and seemed too anxious to lead the march. King had affectionately called Williams my wild man, but for Abernathy his wildness appeared reckless.

Yet Abernathy put aside his personal feelings and tried to consider what was best for the movement. He told Williams that hed call King.

Abernathy reached King on the phone at his own church, Ebenezer Baptist, where he too was preparing to lead services. He told King about Williams proposal to go ahead with the march. There was a long pause at the other end of the line.

Do you think we ought to let him go ahead? King asked.

Abernathy knew King valued his opinion and he didnt hesitate to give it. If he wants to get his [behind] beaten, then let him do it, replied Abernathy. Because if we dont, hell blame us the rest of his life, saying he could have done this or that.

Tell him he can go, King said.

Abernathy immediately called Williams back. Hosea, go to it, he said.

Were gone, shouted Williams into the phone.

Jim Clark

Selma, Alabama, March 7, 1965, Noon

Sheriff Jim Clark looked at his deputies with pride as they flexed their clubs and whips. Then he looked at his clean shirt and the big button on it. The button bore just one word, NEVER. It expressed Clarks feelings about integration in Dallas County. For months, Clark had backed up his words with action. He had ruthlessly beaten up and arrested both black and white demonstrators whom he felt disturbed the peace.