Chapter One

All Eyes on the Bridge

Around 48 million Americans were wrapping up their weekend on Sunday night, March 7, 1965, by watching an award-winning movie on ABC TV. But at 9:30 p.m. Eastern Standard Time the evening took an unexpected turn. News anchor that left them stunned.

Hours earlier, a quiet scene had unfolded on a cool spring day in Selma. Two men stepped onto a steel bridge, walking side by side along the narrow walkway, their hands tucked into the pockets of their buttoned coats. Below them, the Alabama River flowed in its zigzagging path between Selma and the state capital of Montgomery. But black activists Hosea Williams and John Lewis were not on a lazy weekend stroll this Sunday afternoon. They were headed to Montgomery. The Edmund Pettus Bridge and then Interstate 80 could get cars and buses there in about an hour. But the men had an astonishing plan. They would travel the 54 miles (87 kilometers) on foota journey that would take days.

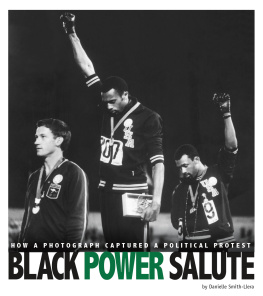

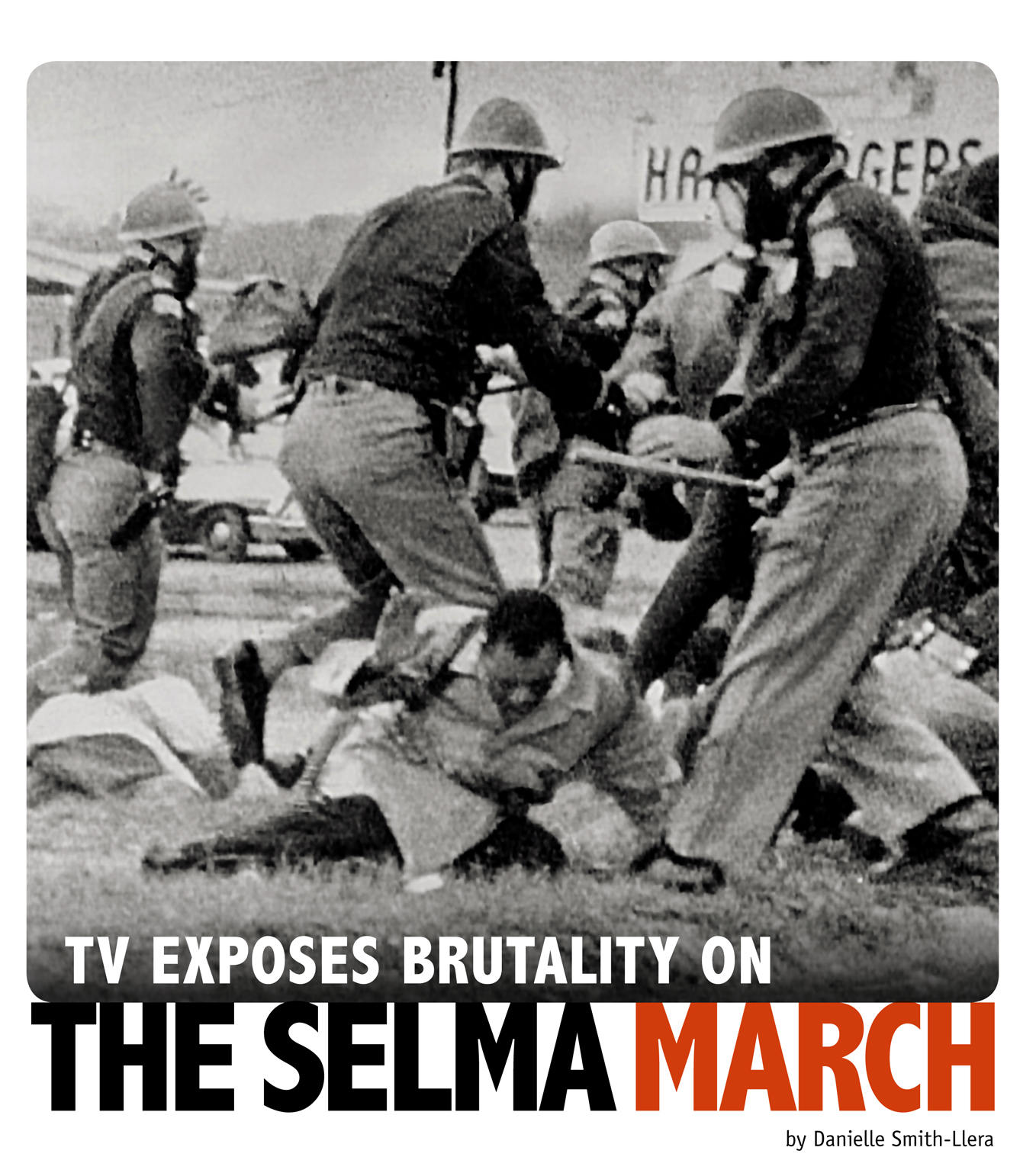

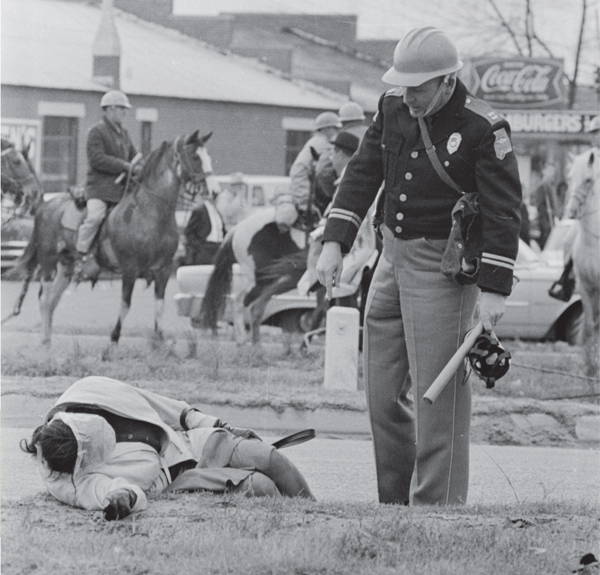

TV viewers saw scenes such as this onetwo marchers holding up another brutally injured in the police attack at the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

Television crews and cameras waited at the other end of the arched bridge to capture this unusual eventparticularly since, behind of black people from white people in public schoolsyet some schools still resisted admitting black students. It had been a year since the Supreme Court outlawed segregation in all public places, but black citizens felt that the greatest right of all was still out of reach.

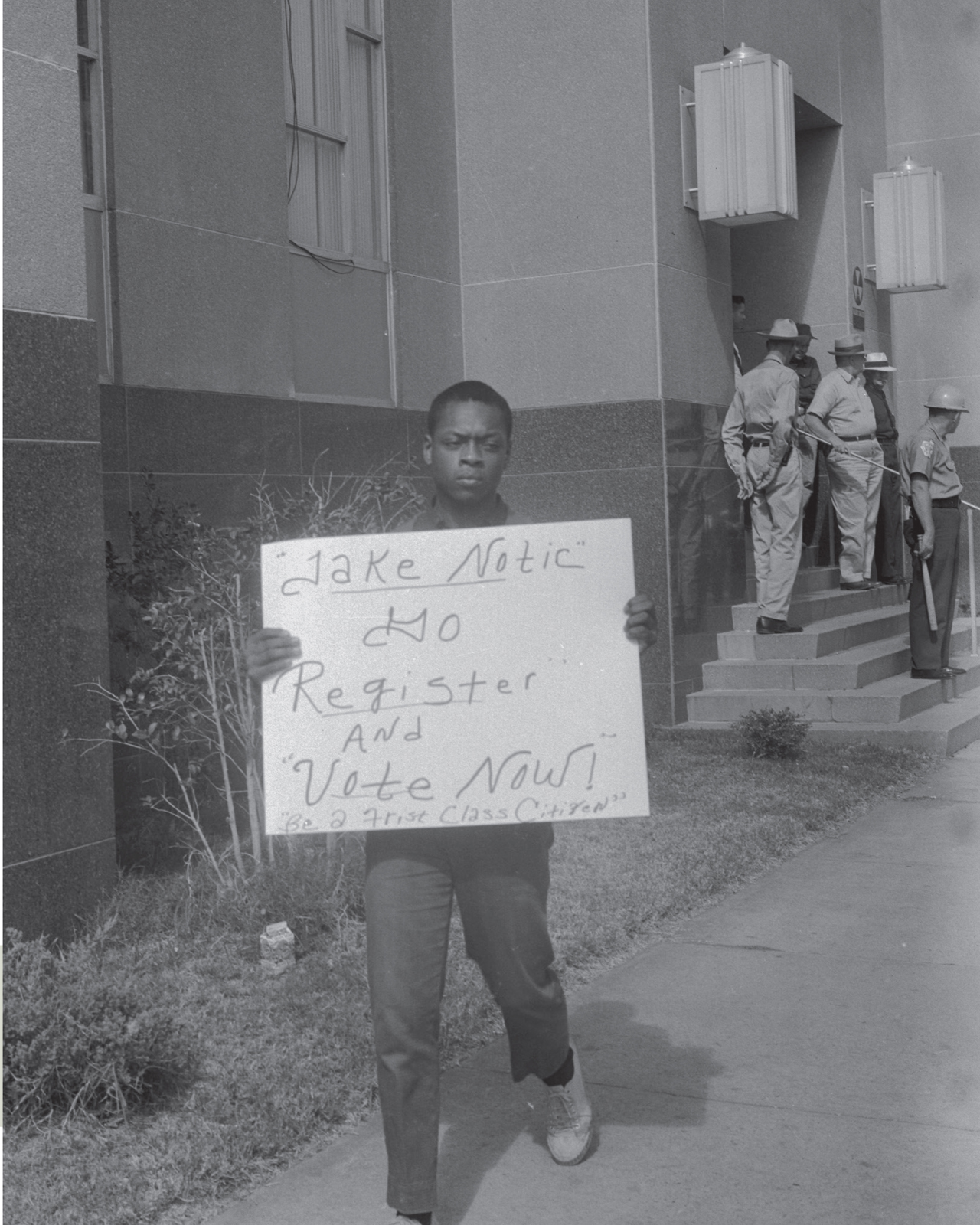

In Selma and across the South, black citizens were blocked from participating in the nations democracy. Half of Dallas Countys 30,000 residents were black, but just 4 percent of them were test. But they were not given the same easy tests as white applicants. The tests for black applicants ranged from overly complicated to outrageous. They might be asked to write long passages from the state constitution or to guess the number of jelly beans in a jar. DENIED was usually stamped on their applications.

The consequences of trying to register could be severe. White employers fired black employees who tried to register to vote. Banks stopped lending money to black applicants, which meant they could lose their homes and businesses. Applicants even faced brutal assaults by local white people. Still, many activists believed it was worth risking everything for the right to vote. The marchers heading over the bridge were on their way to Montgomery to see Alabama governor George Wallace and demand their right as U.S. citizens to become registered voters.

Young people led the voting rights movement in the South.

When the marchers reached the bridge, they had traveled less than a mile from where they had gathered at Selmas Martin Luther King Jr. had visited Brown Chapel on January 2. He stood at the pulpit to announce an ambitious plan. He invited listeners to join a campaign to help everyone in Alabama exercise their right to vote.

In the two months following, activists did indeed join this Give us the ! campaign. They had gathered at Brown Chapel to march to the courthouse together in groups of more than 100.

Brown Chapel was a meeting place for civil rights events. The renewed voter registration drive was kicked off there.

Sheriff Clark made the courthouse a dangerous place.

But as the protesters walked away from Selma,

As the marchers crossed the John Cloud. Behind them stood Clark and his men, some on horseback and hefting clubs. Waving Confederate flags at the roadside, dozens of white people cheered eagerly for a showdown with the marchers.

Another group of white men had been watching the marchers cross the bridge. They were armed toobut with notepads and pens, cameras and sound equipment. For Sheriff Clark and Major Cloud, these tools made them dangerous witnesses to what was about to happen. Four troopers were posted to confine the reporters and photographers to a parking lot about 100 yards away from the foot of the bridge. But these experienced journalists would get their story. Like civil rights activists, they had learned how to do their work even when laws and hostile police stood in their way.

Sheriff Jim Clark (right) gave permission to a number of white men to use violence against protesters. He even supplied the clubs and hard hats.

When just 50 feet (15 meters) separated the unarmed marchers and the armed men, But as the first marchers began to drop down with bowed heads, Cloud shouted an order to his men: Troopers, advance! Rows of armed men shot forward with clubs raised.

A trooper struck Lewis on the head. He fell to the ground and the club struck again. He lay with a fractured skull as the scene wheeled dizzily around him. Tear gas exploded out of canisters and the toxic, gray cloud choked Lewis. He thought, People are going to die here. Im going to die here. Around Lewis, marchers wept and bled, vomiting from the tear gas. He saw Clarks men ride their horses over the bodies of fallen people, swinging whips, clubs, and electric cattle prods. Lying nearby, another march leader sprawled in deathlike stillness where a state trooper had beaten her. Fifty-three-year-old activist Amelia Boynton had been fighting for voting rights in Dallas County since the 1930s. Marchers carried her back to Brown Chapel, where hundreds retreated in a panic. Lewis made it back too. By the end of the day as many as 70 marchers were injured, with at least 17 hospitalized.

No one died on the day that became known as Bloody Sunday. But the images that day produced what would be the most dramatic filmed coverage of a protest in civil rights history. Even marchers themselves would need to see the footage to understand what happened.

After losing cameramen peering into the tear gas and chaos to tell the marchers, the nation, and the world what had happened.

A state trooper stood over Amelia Boynton after she was attacked during the march.

But as they filmed,

The national television camera crews raced to catch rides to Montgomery, where they used the darkrooms and chemical baths at local television stations to develop the film. The images on the film strips could be viewed once they were projected onto a screen. Packed into round canisters, the developed film traveled by plane to the New York City headquarters of TV networks. Editors and producers viewed the film to decide what to show and when to show it. CBS and NBC wasted little time in broadcasting it on the Sunday evening news.

In his Selma hotel room that night, newspaper reporter Roy Reed of The New York Times watched on TV the event he had witnessed with his own eyes at the bridge. Pierces skill and bravery awed him. He had gotten closer than any other cameraman to the violence with his bulky camera. CBS correspondent Nelson Benton presented just 3 minutes, 15 seconds of footage. It began with the camera moving between the approaching marchers and the wall of waiting law enforcement. It ended with screams as parked cars and tear gas blocked the horror. There was no way print could capture the drama and the vicious attack on the demonstrators on Bloody Sunday the way TV did, NBC correspondent Richard Valeriani later said. I put it on the air with hardly any narrative. I said something like, Civil rights activists demonstrating for voting rights tried to march from Selma to Montgomery today but were stopped by Alabama state troopers. Heres what happened.