Published in 2020 by New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2020 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2020 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Alex Ward: Editorial Director, Book Development

Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Wendy Wong: Editor

Greg Tucker: Creative Director

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Civil rights advocates / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York : New York Times Educational Publishing, 2020. | Series: Public profiles | Includes glossary and index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781642822397 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642822380 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642822403 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansCivil rightsSouthern StatesHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. | African AmericanCivil rights workersJuvenile literature. | Civil rights workersUnited StatesJuvenile literature. | Civil rights movementsUnited States20th centuryJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC E185.96 C585 2020 | DDC 323.11960730904dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

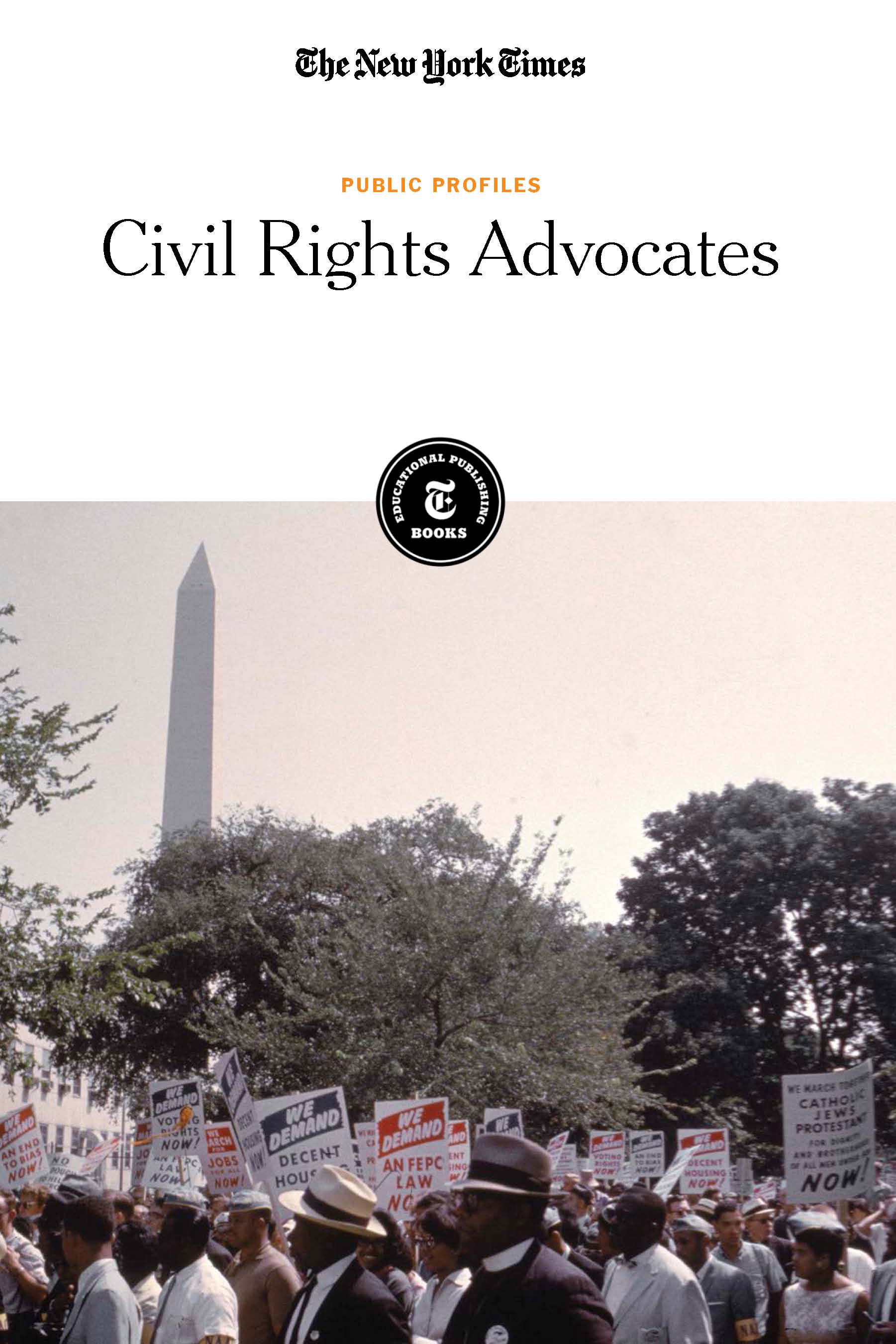

On the cover: Civil rights demonstrators walk with placards at the March on Washington, August 28, 1963; Bob Parent/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

Introduction

IN THE 1950S, black Americans, burdened by the systemic oppression and inferior treatment they encountered, organized and protested to end racial discrimination. They worked to overthrow the Jim Crow laws that upheld racial segregation throughout the South and establish equal rights in the United States. This period of time, spanning over a decade, came to be known as the civil rights movement.

In a time where protests and social movements were almost unheard of, African-Americans actions, carried out through various demonstrations such as public speeches, sit-ins and marches, forever changed the way people of color were treated and able to live in the United States. Men, women and children came together and protested for simple liberties such as riding a bus, eating lunch at a restaurant or going to school. They sought social and legal action, highlighting the injustices they had faced and reaching out to law enforcement and American citizens to join them in correcting a wrong that had gone unchecked for decades. They persisted despite all the threats and violence they encountered. They wanted black voices to be heard and black bodies to be respected. They wanted to be recognized as humans and as equals.

These calls to action were not organized and carried out on two or three peoples shoulders alone. It took hundreds of ordinary citizens to do extraordinary things, and all of their contributions were crucial in taking steps forward for equality. Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on the bus. Thurgood Marshalls tremendous work as a lawyer for the N.A.A.C.P., which itself was an organization at the forefront of fighting for black rights, compelled the Supreme Court to strike down segregation in schools and allowed progress to take root in the legal system. A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin organized the March on Washington. Four black students bravely sat and asked for service at a Woolworth whites-only lunch counter, one of the most well-known sit-ins of the movement. The SCLC, CORE and SNCC all made irreplaceable contributions to the cause, planning rallies and meeting with political figures to give advice on legislation.

American civil rights campaigner Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife Coretta Scott King lead a black voting rights march from Selma, Ala., to the state capital in Montgomery in March 1965.

However, among these figures were those who also became emblems of social action in the media. These leaders inspired and swept the nation into a frenzy with their perseverance in the face of doubt and hatred. Their actions and words gained nationwide attention and had a country clinging to every piece of news. The Little Rock Nine were students aspiring to receive a better education to put them on equal footing with their peers. Daisy Bates, their mentor and head of the Arkansas branch of the N.A.A.C.P., protected their best interests and guided them toward successful school integration. The Freedom Riders were a diverse collective that set out to test existing laws in public transportation segregation. Others, such as Martin Luther King Jr., Coretta Scott King and Malcolm X, had very different approaches. Yet all three took to the front lines with a long history of advocating for equality and encouraging their fellow black citizens to mobilize and have pride in their identity.

Though these public figures encountered much scrutiny and doubt throughout their lives, their impact on society lives on. They shined a spotlight on lawmakers ineptitude and struggled for African- Americans to receive the protection and equality they deserved as citizens. They made sure an entire community could no longer be silenced and forced into compliance. These landmark actions have been immortalized in history as some of the most crucial stepping stones of the civil rights movement.

CHAPTER 1

Daisy Bates and the Little Rock Nine

On May 17, 1954, the Brown v. Board of Education case struck down segregation in schools. A few years later, nine black boys and girls enrolled in Central High School in Little Rock, Ark. This became a high-profile case documenting the ongoing tension in Little Rock as they were met with angry mobs, threats from other students and an uncooperative governor. Despite this, they remained determined and were able to attend classes thanks to encouragement and guidance from Daisy Bates, president of the Arkansas branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.).

Militia Sent to Little Rock; School Integration Put Off

BY BENJAMIN FINE | SEPT. 3, 1957

LITTLE ROCK, ARK., TUESDAY, SEPT. 3 Gov. Orval E. Faubus sent militiamen and state police last night to Little Rock High School, where racial integration had been scheduled to start today.

The Governor, a foe of integration, said troops were necessary to prevent violence and bloodshed at the school.

By early morning about 100 members of the state militia had surrounded the school. They were armed with billy clubs, rifles and bayonets. Some carried gas masks.

The Board of Education met with Dr. Virgil Blossom, Superintendent of Schools, late last evening to consider the new developments. It then issued a statement appealing to Negroes not to attempt to pass through the line of troops. The boards statement said:

Although the Federal Court has ordered integration to proceed, Governor Faubus has said schools should continue as they have in the past and has stationed troops at Central High School to maintain order.