Published in 2020 by The New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2020 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2020 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Alex Ward: Editorial Director, Book Development

Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Jacob R. Steinberg: Editor

Greg Tucker: Creative Director

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: The death penalty / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York : New York Times Educational Publishing, 2020. | Series: Changing perspectives | Includes glossary and index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781642822243 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642822236 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642822250 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Capital punishmentUnited StatesJuvenile literature. | Capital punishmentJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC HV8699.U5 D343 2020 | DDC 364.660973dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

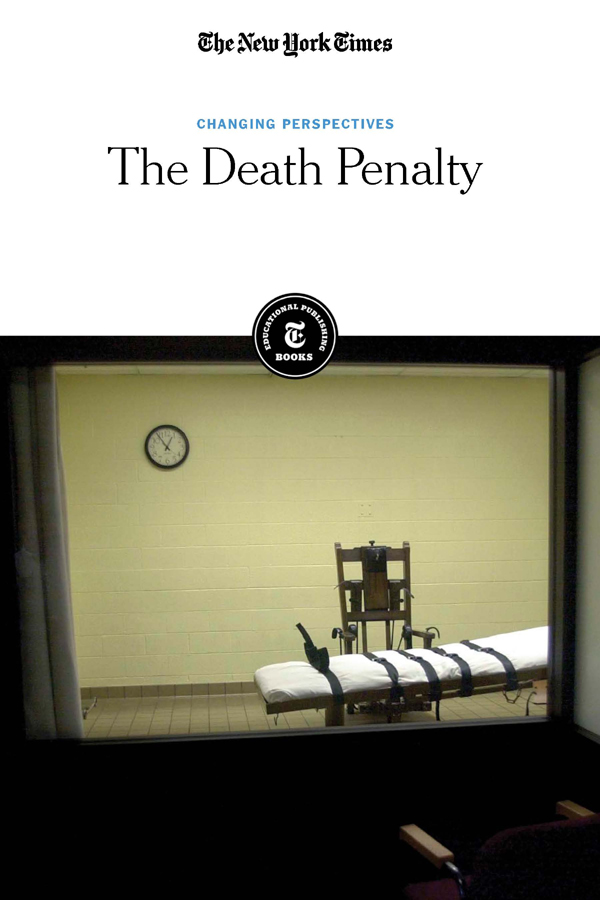

On the cover: A view of the death chamber from the witness room at the Southern Ohio Correctional Facility in Lucasville, Ohio, Aug. 29, 2001; Mike Simons/Stringer/Getty Images.

Introduction

WHILE IN INTERNATIONAL forums the United States often revels in its identity as the standard-bearer for democracy and human rights, there is one practice that it continues to engage in that places it in the uneasy company of the likes of China, Iran and Saudi Arabia, among other flagrant violators of human rights. That practice is its continued use of the death penalty.

Whereas the majority of the Western world has gradually eschewed the practice over the last century or so, the United States has ignored calls from international bodies and humanitarian groups to abandon the death penalty. In fact, certain states persist in rewriting their statutes to pass the continually higher bar set by the courts for when and how the death penalty may be applied.

This disparity between begs the questions: Why is the death penalty so entrenched in the American legal system? Why do a majority of Americans (as shown by popular opinion polls) continue to support a practice found barbaric by most of their allies abroad? The answers arent so simple.

Capital punishment has always been part of the American criminal justice system. In colonial times, the American system of law was derived from the English penal code and bore religious tinges. Infractions that today seem minor warranted an execution in some colonies, including the crimes of denying God, cursing a parent, stealing grapes or trading with Native Americans.

Not all colonies, however, were quite as bloodthirsty as others. Notably, areas with Quaker influence, such as Pennsylvania and West Jersey, limited the use of capital punishment to cases of treason or murder.

The courts have become the main arena for advocates and opponents of the death penalty. Cases reviewed by the Supreme Court have faced particular public scrutiny.

By the late 1700s, a true abolitionist movement had begun to form in the United States. One prominent abolitionist was Dr. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, who called the death penalty un-Christian and challenged its deterrent effect. Several states limited the list of crimes for which offenders could be sentenced to death, and further, some prohibited public hangings.

Throughout the 1800s, many states abolished the practice only to later reinstate it, and an abolitionist wave between 1907 and 1917 came to a halt as public fervor again prompted its return in several of the states that had banned it.

Since the 1960s, the greatest challenge to capital punishment has not come from the legislatures, but the courts. The N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense and Educational Fund adopted a successful strategy of challenging the practice in courts on grounds that it violated the Eighth Amendments protection from cruel and unusual punishment.

The cruxes of such legal challenges have varied from focus on the inconsistent application of the death penalty to different types of defendants often influenced by racial prejudice to legitimate concerns over the painlessness and effectiveness of different means of execution. Because of such challenges, the death penaltys application has been greatly limited.

While a unidirectional historical trajectory can be plotted for many social issues, the death penalty has seen waves of support and challenges. As courts further curb its use in response to evolving standards of decency, legislatures concoct new standards of application that they hope will pass muster when legally challenged. And much like in the colonial era, support and rejection of capital punishment varies greatly by state. Indeed, just a handful of states among them Texas, Virginia, Oklahoma and Florida execute a disproportionately high number of offenders compared with the rest of the country.

The articles that follow explore the many diverse perspectives on a heated topic, taking into account religious, medical and legal perspectives on what is literally a matter of life and death.

CHAPTER 1

The Ultimate Punishment, but Is It a Deterrent?

One of the strongest arguments for maintaining the death penalty has been that it is a deterrent to crime. Its supporters believe fear of capital punishment causes would-be criminals to think twice before committing a violent offense. Detractors argue that its inconsistent application in different states and to different types of defendants nullifies that argument. The following articles focus on the death penaltys ability or failure to prevent crime.

Is the Death Penalty an Actual Check to Crime?

BY THE NEW YORK TIMES | MAY 16, 1909

Dr. Edward C. Spitzka gives the results of recent investigations.

THAT THE ABOLITION or practical abrogation of the death penalty in European countries has made unsafe the lives of the sovereigns of those countries and has made it dangerous for other rulers to visit them such is one of the conclusions which seem inevitable after a conversation with Dr. Edward C. Spitzka, the noted New York alienist, who has made a special study of these subjects.

Another is that by the abolition of the death penalty in these countries it has been demonstrated what it has been impossible to demonstrate hitherto that capital punishment does deter criminals from crime in greater degree than does imprisonment.

Another is that the reformation of such a criminal by a life in prison is an iridescent dream.

In talking of his researches, Dr. Spitzka explains that for purposes of a fair comparison it is necessary to take a group of murderers of the same class, and most of his illustrations, therefore, are drawn from regicides and Anarchists.