Cruel and Unusual Punishment

Should the death penalty be considered cruel and unusual punishment? This was the question brought before the United States Supreme Court in 1972. In Furman v. Georgia: The Death Penalty Case, author D. J. Herda examines the ideas and arguments behind this landmark case. Presented in a lively, thought-provoking overview, Herda brings to life the people and events of this controversial decision and sheds light on the current controversy still raging across the country today.

About the Author

D. J. Herda is a full-time freelance writer with more than eighty books and several hundred thousand short features to his credit. He is president of the American Society of Authors and Writers and a widely heralded photographer, teacher, graphic artist, painter, and sculptor.

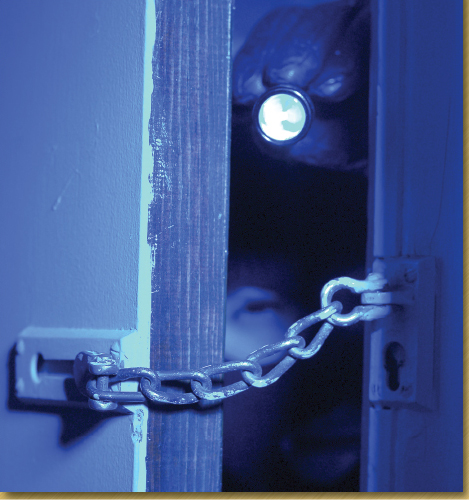

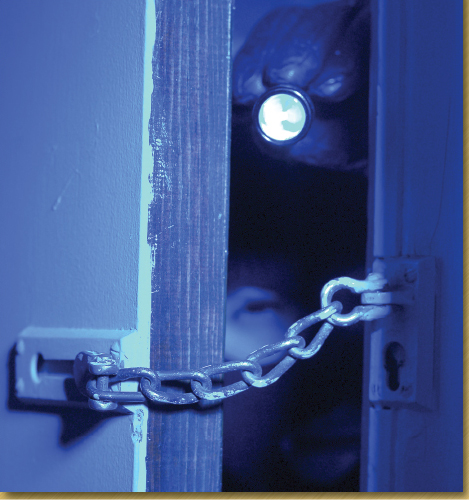

Image Credit: Photos.com/Jupiterimages Corporation

The Furman case began with an attempted burglary in a Georgia home in 1967.

William Henry Furman, a twenty-six-year-old black man with a sixth-grade education, was not what most people called a bad man. He was, by his own admission, down on his luck. Recently laid off from his job, he bounced around his home state of Georgia for months. Everywhere he went he looked for a job, any job. He found his share of work, too, over the months, but none of the jobs were very good, and none were permanent. He went from gardener to dockworker, from janitor to delivery man. But no matter how hard he tried to get ahead, the jobs always ended too soon, and in time his money ran out.

Furman began showing signs of depression. He became sullen and moody. Eventually, hungry and broke, he turned to breaking and entering and to petty thievery to survive. Nothing major, according to Georgia State Patrol records.

A few things here, a few there. Mostly, he would look for a likely house and plan his assault well after dark, when the residents were either away or sure to be asleep. Then he would sneak in an open window or jimmy a locked door, rummage around for whatever valuables he could find, and be gone, usually within ten or fifteen minutes.

He had been caught a couple of times and each time was given a light or suspended sentence. He had been examined once by a state-appointed psychiatrist, who had found him to be emotionally disturbed and mentally impairedbut not enough to have him held in jail or committed to a mental institution. Usually he was back on the streetsand struggling to survivewithin a matter of weeks.

Then on August 11, 1967, Furmans luck took a turn for the worse. He had just broken into the home of twenty-nine-year-old William Joseph Micke, Jr., the father of five young children. While Micke, his wife, and his children slept upstairs, Furman rifled through the lower level of the house for whatever valuables he could find.

Suddenly, around 2 A.M. , Micke awoke to the sound of someone rummaging around downstairs. He crawled out of bed and made his way slowly toward the kitchen. The noises grew louder.

Furman, too, heard noisesthe steadily approaching footsteps of William Micke. He pulled out the gun he had brought along with himjust in case he had to scare someone away. He paused and listened to the footsteps. Closer and closer they came. Not wanting to risk a confrontation, Furman turned and fled through the back door leading to the porch. As he ran, he tripped over an exposed washing machine cord and fell face-first against the hardwood floor. The gun discharged. The stray bullet pierced the back door. On the other side, Micke slumped slowly to the floor. William Joseph Micke was dead.

The police responded to the call quickly, and within minutes they had apprehended Furman just down the street from the scene of the crime. The murder weapon was still in his pocket. When his trial came up, Furman, on the advice of his court-appointed attorney, pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. The courts ordered a psychiatric test, and the physicians who examined him agreed unanimously that he was mentally deficient. In their report they concluded that Furman experienced mild-to-moderate psychotic episodes associated with convulsive disorder.

The physicians testified in court that Furman was not psychotic at the time of his examination, but they agreed that he was not capable of cooperating with his defense attorney in the preparation of his own case. They concluded that he was in need of further psychiatric hospitalization and treatment.

Several days later, the superintendent of Georgias Central State Hospital, where Furman had been committed while awaiting trial, revised his own earlier medical opinion after finding that Furman was not psychotic at present, knows right from wrong, and is able to cooperate with his counsel in preparing his defense. The court then ruled that William Henry Furman was competent to stand trial for murder in Chatham County Superior Court. Although the killing of Micke had been accidental, or at least committed without any intent to kill, Georgia state law at the time authorized that the death penalty be given whenever a murder took place during the commission of a felony, a class of crimes that includes burglary. Furman was tried, convicted, and scheduled for sentencing. Faced with imposing either life imprisonment or death on Furman, the jury chose death.

William Furmans attorneys were shocked. Their client was a man whom society had literally forgotten. He had seemed genuinely sorry for Mickes death. He had been down on his luck. He had turned to burglary only as a last-ditch effort to survivewhile quite possibly being plagued by psychotic bouts.

But William Furman had one other thing going against him. He was black. And Georgia crime statistics showed that like most blacks found guilty of committing murder in that state during the sixties and seventies, that fact alone was reason enough to sentence him to death.

There were still various legal avenues open to Furman and his attorneys before the death sentence was carried out. There were motions to be filed. There were appeals to be made. And if it came right down to it, there was one last road to take. There was the Supreme Court of the United States.

Nearly six hundred inmates sat on death row in Americas prisons at the time Furman was convicted of murder. They sat and they waited for someone to come and tell them their appeals had run out. They sat and they waitedthinking and hoping and praying, most likelyuntil someone arrived to pull the switch.

Of those death row inmates, several were teenagers, more than twenty were women, and a disproportionate number were blacks (329 blacks, 257 whites, and 14 identified as Puerto Rican, Chicano, or Native American). Yet no one had previously made a serious challenge to the death penalty based on the grounds that it discriminated against the nations poor and oppressed.

The death penalty, or capital punishment, has been a common ingredient in Americas judicial system since the systems Anglo-Saxon beginnings. Capital punishment had existed in Plymouth Colony and throughout much of New England since the early 1600s. It has existed throughout most of America ever since.

The death penalty in early America was usually the result of a criminal conviction for murder. But capital punishment was also handed out for a variety of other crimes. As many as eighteen different capital crimes existed on the law books of colonial America, depending upon the individual colony. In some colonies so many offenses were punishable by death that it seemed few other punishments existed.