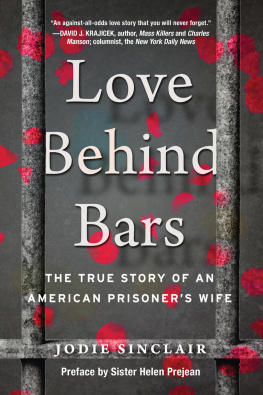

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

CAPITAL PUNISHMENT

An Indictment by a Death-Row Survivor

BILLY WAYNE SINCLAIR

and JODIE SINCLAIR

Foreword by Sister Helen Prejean

Copyright 2009, 2011 by Billy Wayne Sinclair and Jodie Sinclair Foreword copyright 2009, 2011 by Sister Helen Prejean

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Arcade Publishing is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.arcadepub.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sinclair, Billy Wayne, 1945

Capital punishment : an indictment by a death-row survivor / Billy Wayne Sinclair and Jodie Sinclair; foreword by Sister Helen Prejean.

p. cm.

Originally published in 2009.

ISBN 978-1-61145-034-7 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Capital punishment--United States. 2.Sinclair, Billy Wayne, 1945- 3.Death row inmates--United States. I. Sinclair, Jodie, 1938- II. Title. HV8699.U5S475 2011

364.66092--dc22

2011001610

Printed in the United States of America

This book is dedicated to Richard Seaver,

an editor with the courage to publish the truth.

The man who opts for revenge should dig two graves.

Chinese proverb

Contents

Foreword

Arguments against the death penalty expose capital punishment for what it is: revenge disguised as justice.

When there is a conviction in a capital case, the prosecutor appears before the jury arguing that it must impose the death penalty because the criminal poses a continuing threat to society. Billy Wayne Sinclairs life refutes that claim. It argues for a different perspective on individuals who have been convicted in capital cases.

His early life is similar to those of other death row inmates in many ways. He was repeatedly beaten as a small child by a brutal father who ultimately abandoned the family. He grew up in extreme poverty with a single mother in rural Louisiana. He dropped out of school in the tenth grade after pushing a school principal to the ground. In 1965, during a bungled robbery attempt when he was twenty years old, Billy killed a convenience store clerk with a wild shot intended to frighten him as he was chasing Billy across a parking lot in the dark.

A year later, a Baton Rouge judge sentenced him to die in Louisianas electric chair. He spent five and a half years in solitary confinement on death row at theLouisiana State Penitentiary at Angola. In 1972 the U.S. Supreme Court struck down the death penalty nationwide, and Billy was resentenced to life.

Today he is a hardworking paralegal for a criminal defense attorney in Houston. He has been married for twenty-seven years to the coauthor of this book, Jodie Sinclair, a former journalist. He is a national awardwinning writer on prison issues, and he was a model inmate during his near half-century behind bars. There are no instances of violence in his prison record.

Billy Wayne Sinclair personifies the humanity of the condemned and their capacity to change. Clearly redemption is not limited to souls without sin.

Sister Helen Prejean

Preface

I served more than forty years in the Louisiana prison system for a murder I committed in 1965. Six of those years I spent on death row.

In April 1966, in a Baton Rouge courtroom, a judge spoke the words that shaped my life from that moment on: Billy Wayne Sinclair, I hereby sentence you to death in the electric chair. The sentence staggered me. I was only twenty-one years old, and I was condemned to die.

Granted, I had created the circumstances that condemned me to that death. I had tried to hold up a Baton Rouge convenience store, and, in a robbery gone wrong, I fired a wild shot in the direction of the store manager who was chasing me in the dark. The bullet nicked his aorta, and he bled to death on the sidewalk.

I grappled at first with the immediate implications of my death sentence. Nearly 3,000 volts of electricity would course through me for two minutes, cooking my brain, while my body convulsed against the chairs thick leather straps. I dealt with the horrifying prospect by denying it. I swallowed daily the tranquilizers that guards handed out to inmates on death row to keep them pacified, and then begged other inmates for their pills. Those pills kept me stoned for six months straight.

When I finally tired of my drug-induced stupor, I confronted my sentence head on. If the system intended to kill me, I wanted to learn everything about the monstrous sins it committed in carrying out the ultimate sentence. I read anything I could find about decapitation, hanging, death by firing squad, and electrocution. I studied the modes and methods of killing, like a scientist peering through a microscope at a deadly bacillus.And for almost six years, I woke up every day to the possibility that guards might drag me from a death-house holding cell, strap me into the electric chair, and put me to death by one of the most gruesome forms of execution ever devised.

That the United States Supreme Courts decision saved me has not erased my fear of, or my fascination with, state-sanctioned murder. Every headline about the death penalty, every controversial court case, every DNA exoneration grabs my attention. I still study capital punishment the emotional and social impact on the condemned, their families, their loved ones, the victims families, and the general public. My death sentence will stay with me for the rest of my life.

I began writing about the death penalty on death row. My first article appeared in a religious pamphlet called Power for Living, earning me $35 for my account of a religious experience I had on death row. Publication elated me. Death didnt have to silence me. I could live through writing. I pounded away feverishly in my cell on a 1922 Underwood typewriter traded for a carton of cigarettes documenting guards abuses and the awful specter of death that twisted human lives into parodies of human experience.

Then, one hot June morning in 1972, the Supreme Court struck down the death sentence nationwide in Furman v. Georgia, ruling that it was being applied inequitably. There was no official announcement. Every man on the row, except those who had gone mad waiting to die, heard the news over the radio. The news stunned us, and we greeted it with silence. Suddenly, at age twenty-seven, I had a future. I could breathe beyond the moment. I stretched out on my prison bunk and immediately fell asleep, exhausted from years of dread.

Louisiana promptly resentenced me to life without parole and moved me into the general population at Angola in November 1972. I held a number of inmate jobs over the years, from stoop labor in the prisons fields, tending crops under the eyes of shotgun-toting guards on horseback, to a desk job clerking for the prisons food manager. But I never gave up writing. I contributed regular articles to two inmate publications at the prison, the

Next page