Person or Property?

Slave or citizen? This was the key question that Dred Scott brought to the United States Supreme Court in May of 1857. Within these pages, author D. J. Herda examines the ideas and arguments behind this landmark case. Presented in a lively, thought-provoking overview, Herda brings to life the people, the case, and the fateful decision that upheld the legality of slavery.

About the Author

D. J. Herda is a full-time freelance writer with more than eighty books and several hundred thousand short features to his credit. He is president of the American Society of Authors and Writers and a widely heralded photographer, teacher, graphic artist, painter, and sculptor.

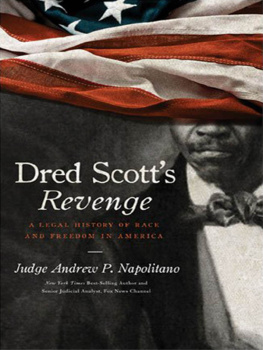

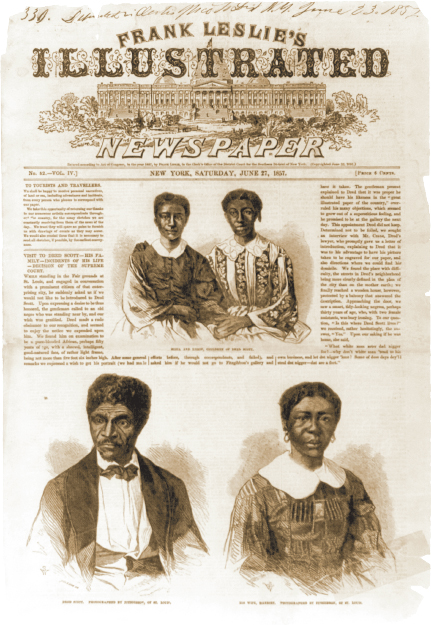

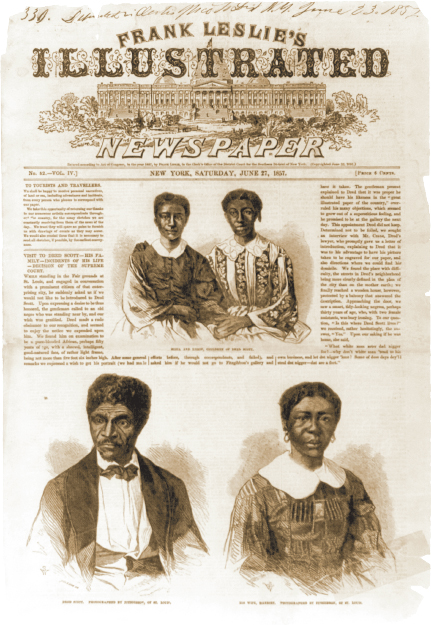

Image Credit: Library of Congress

The front page of Frank Leslies Illustrated Newspaper of June 27, 1857, features the Scott family. In the top image, Dred Scotts youngest daughter, Eliza, is shown on the left. Lizzie, Dred Scotts oldest daughter, is shown on the right. The bottom image is of Dred Scott and his wife, Harriet, soon after they were married.

Dred Scott cradled his daughter Eliza in his arms as his wife, Harriet, put the last of their meager possessions into the wagon that would carry them to a steamboat bound for St. Louis, Missouri. His second daughter, Lizzie, climbed aboard, and as Scott loaded the youngest child, Harriet began to cry. But hers were not tears of sadness. They were tears of joy. The Scotts were going home.

Come along now, Dr. John Emerson called. No time for that. Weve a long trip ahead of us.

Yes-suh, Scott replied. Yes-suh, we sure do. Scott helped his wife aboard, then climbed in after her. As the couple settled down with their daughters, Emerson gave the order to move out, and the wagon lurched suddenly forward.

It was spring, 1840, in Fort Snelling, Minnesota, part of the sprawling Wisconsin Territory. Scott had accompanied Emerson, an army physician, from Missouri two years earlier. While in the North, Scott had met and married Harriet. Now they were returning home to St. Louis. Not to their home, but to Emersons home: Scott, his wife, and their daughters were slaves.

Slavery was still an important part of the economy of the South in 1840. Slavery had long been banned north of a line roughly equal to the southern boundary of the state of Missouri. But Congress, in passing the Missouri Compromise of 1821, had created a special exemption for that state, allowing Missouri to retain slavery.

The issue nonetheless remained a thorn in the side of Northern political leaders, who saw slavery as an immoral and shameful institution. Southern leaders, on the other hand, needed inexpensive slave labor to help run their cotton, tobacco, and rice plantations.

By 1840, the debate over slavery had mostly died down. But Dred Scott was destined to change all that. He was destined to change his own future and that of his country, too.

Dred Scott was born in Virginia around 1800. The exact date was never recordednot an unusual circumstance for the birth of slaves. He was the property of Peter Blow, a Virginia farmer. In 1818, Blow sold his 860 acres and moved with his wife, Elizabeth, his family, and his slaves to a cotton plantation near Huntsville, Alabama. Two years later, Blow moved again, this time to nearby Florence, Alabama. Finally, in 1830, he settled for good in the bustling Missouri riverfront town of St. Louis, the gateway to the West, on the mighty Mississippi River.

In St. Louis, the Blow family had to adapt to a completely different lifestyle. Rural Virginia and Alabama had been predominantly cotton-growing country. But St. Louis, with its excellent port facilities, was geared almost exclusively toward commerce, trade, and manufacturing. Blow rented a large home for twenty-five dollars a month and opened a boarding house, which he named the Jefferson Hotel. There, Dred Scott and the other Blow slaves workednot in the fields, though, planting and hoeing and picking cotton, but in the hotel, cleaning and cooking and running errands. It was quite a change for Scott, who had never known anything besides farming.

In 1831, tragedy struck the Blow family when Peter Blows wife, Elizabeth, died. Early the next year, Blow sold the hotel and moved his family into another house. In the months that followed, Blows own health failed, and he died on June 23, 1832, leaving the family fortunes in the hands of his eleven children.

Although no records of this have been found, according to Henry T. Blow, his father apparently sold Dred Scott to Dr. John Emerson, a St. Louis physician, who was about the same age as Scott. Emerson had moved to St. Louis in 1831 and had quickly befriended such well-known local figures as Missouris U.S. senators, Thomas Hart Benton and Alexander Buckner. He was also a friend of Dr. William Carr Lane, the first mayor of St. Louis; William H. Ashley, a Missouri congressman; and several members of the Missouri state legislature. Indeed, Emerson seems to have been better suited to making influential friends than practicing medicine, a profession in which he apparently was poorly trained and only marginally effective.

Nonetheless, on October 25, 1833, Emerson, who had applied for a position with the U.S. Army, was accepted into the armed forces and appointed to the position of assistant surgeon. But it was not his skill alone that got him the appointment. Just when it looked as though he would be passed over once again, having tried to gain a commission for years, Emerson asked some of his most influential friends to come to his aid. Thirteen members of the Missouri state legislature signed a letter recommending him, as did Senator Benton. The following month, Emerson received new orders and moved to Fort Armstrong, on Rock Island, Illinois, taking Scott with him. Emerson reported to his commander, Lieutenant-Colonel William Davenport, to begin what would eventually become a nine-year military career.

But life at Fort Armstrong proved less than comfortable. The forts old log buildings were rotted and falling apart, and the roofs of the soldiers barracks leaked with every rain. Undoubtedly, the slave quarters were even worse. Despite frequent outbreaks of cholera and other diseases, Scott remained at Emersons side, in service to the physician as a slave and used by him as such. In fact, Illinois had prohibited slavery since 1787, when the Congress of the Confederation passed the Northwest Ordinance, which banned slavery in the region. Scott could have sued for his freedom on the grounds that he was living in a free territory. For some reason, he did not. Instead, he stayed at his masters side.

Meanwhile, Emerson was unhappy with life on the plains. Within two months of his arrival at Fort Armstrong, he asked his commander for a leave of absence, claiming that he had contracted a syphiloid disease during a visit to Philadelphia. When his leave request was denied, Emerson once again enlisted his friends to pressure the War Department to transfer him back to St. Louis. Emerson himself informed the department that his left foot had developed a slight disease that might require surgery. In January 1836, he tried again, complaining that he had had an argument with one of his company commanders and could no longer work for the man.

Despite his dissatisfaction with his position, Emerson did reap some rewards from his assignment. He bought several acres of land near the fort, along with an entire section across the Mississippi River, near present-day Davenport, Iowa. There, Emerson had Scott build a small cabin.