Dred Scott and the Dangers

of a Political Court

Dred Scott and the Dangers

of a Political Court

Ethan Greenberg

Published by Lexington Books

A division of Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

http://www.lexingtonbooks.com

Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom

Copyright 2009 by Lexington Books

First paperback edition 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The hardback edition of this book was previously cataloged by the Library of Congress as follows:

Greenberg, Ethan, 1957

Dred Scott and the dangers of a political court / Ethan Greenberg.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Scott, Dred, 18091858Trials, litigation, etc. 2. Sanford, John F.A., 1806 or 71857Trials, litigation, etc. 3. SlaveryLaw and legislationUnited StatesHistory19th century. 4. Political questions and judicial powerUnited States. I. Title.

KF228.S27G74 2009

342.73087dc22

2009032656

ISBN: 978-0-7391-3758-1 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-0-7391-3759-8 (pbk : alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-0-7391-3760-4 (electronic)

Printed in the United States of America

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Dedication

For David and Marilyn, who came before;

For Eli and Ruby, who will go on after;

And for Marly,

The sweet heart of the heart of my life.

Contents

Acknowledgments

First and foremost, I wish to acknowledge and thank Fred Gilbert. He has been endlessly helpful (and endlessly patient) in putting this book together. Without Fred, this project could never have been finished.

Professor Philip Weinberg (of St. Johns Law School) and Dean Evan Cornog (of Columbia Journalism School) read various drafts of this book; they provided valuable comments and welcome encouragement. So too did Ruth Greenberg and Jessica Levinson. Joyce Seltzer (of Harvard University Press) and Helen Tartar (of Fordham University Press) also helped to shape this book with their useful comments.

Bronx Supreme Court Librarian Margaret Beirne was able to locate even the most obscure sources, quickly and cheerfully.

It is customary for the author to acknowledge the people who helped along the way, and to take sole responsibility for any faults the book may have. Thats certainly appropriate here. I thank all these people for their help. They could not have been kinder or more able. This books flaws are purely of my own making.

* * *

I am also grateful to the following sources for permission to reprint excerpts of their work.

Alan M. Dershowitz, America on Trial: Inside the Legal Battles That Transformed Our Nation (New York: Warner Books, 2004), 118. Reprinted by permission.

Christopher Eisgruber, The Story of Dred Scott: Originalisms Forgotten Past, in Constitutional Law Stories, ed. Michael C. Dorf (New York: Foundation Press, 2004), 155. Reprinted by permission.

Walter Murphy, James Fleming, Sotirios Barber, and Stephen Macedo, American Constitutional Interpretation (3d Ed.) (New York: Foundation Press, 2003), 218. Reprinted by permission.

Introduction

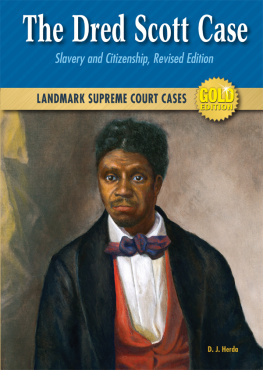

More than 150 years ago, in May of 1854, in a small and stuffy courtroom in St. Louis, Missouri, a jury returned a verdict for the defendant John Sanford in the federal court freedom suit of Dred Scott v. Sanford. The jurys verdict declared that the plaintiffs Dred Scott and his wife Harriet Scott (together with their two young daughters, Eliza and Lizzie) were still slaves who belonged to Sanford.

The Scotts had sued for their freedom on the grounds that their former owneran obscure Army doctor named John Emersonhad taken the Scotts to live with him on free soil. Specifically, Dred Scott had served as Emersons slave for roughly six years back in the 1830s at remote Army posts along the Indian frontier. Those posts were located in Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory. Slavery was illegal there (although Dr. Emerson and his fellow Army officers ignored that fact). Dred Scott therefore argued that he had become free by living in Illinois and in the Wisconsin Territory, and he based his lawsuit in large part on the legal doctrine Once free, forever free. But the jury did not agree. Following the instructions on the law given by trial Judge Robert Wells, the jury found that Dred and Harriet Scott had not been emancipated, despite their extended residence on free soil.

The parties to the Dred Scott case were fairly ordinary people. By the time they brought their federal lawsuit against John Sanford, Dred and Harriet Scott had become household slaves in St. Louis. Dred Scott served mostly as a doorman and porter. Harriet Scott took in laundry. Their former master Dr. Emerson had passed away quietly in 1843, shortly after leaving the Army. Ownership of the Scotts later passed from Emersons widow to her brother, John Sanford. Sanford was a wealthy but largely unremarkable New York City businessman who traveled frequently to St. Louis in order to look after his financial interests there. It seems likely that no one would remember any of these people today had the Scotts simply accepted the jurys verdict.

But the Scotts did not give up. They brought an appeal to the United States Supreme Court; and the decision of the Supreme Court in Dred Scott v. Sandford in 1857 was a landmark in the history of the Court and of the United States.

The Opinion of the Court in Dred Scott was written by Chief Justice Roger Taney. It held that free Negroes (like Negro slaves) were not and could not be citizens of the United States. Even more important, Dred Scott declared that the Missouri Compromise of 1820 was unconstitutional. The Missouri Compromise had in substance forbidden slavery in all the U.S. territories north of Missouri.

Dred Scott was the very first case in American history where the Supreme Court set aside a substantive federal statute as unconstitutional. That was an historic and controversial development in itself. Moreover, the Dred Scott decision held that Congress had no power to prohibit slavery in any federal territory. That decision flew in the face of a long-established national understanding; from the very outset of U.S. history, Congress had passed numerous laws deciding which U.S. territories (and thus which future states) would be free, and which would have slavery.

The Dred Scott decision demonstrated to most neutral observers (although there were, admittedly, very few neutral observers at the time) that the Supreme Court was firmly committed to the defense of slavery. The decision appeared to be an attempt by the Court to resolve in favor of slavery the most hotly disputed political issue of the daythe future of slavery in the territories that made up the great American West. Not surprisingly,

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.