Freedom of the Press!

Should news providers be allowed to publish stories that may prove embarrassing to the United States government? This was the question the United States Supreme Court had to consider in the case of New York Times v. United States in 1971. Author D. J. Herda examines the mood of the country during this time, along with the ideas and arguments behind this landmark case. Presented in a lively, thought-provoking overview, Herda brings to life the people and events of this decision maintaining freedom of the press.

About the Author

D. J. Herda is a full-time freelance writer with more than eighty books and several hundred thousand short features to his credit. He is president of the American Society of Authors and Writers and a widely heralded photographer, teacher, graphic artist, painter, and sculptor.

Image Credit: Enslow Publishers, Inc

A map of Vietnam at the time of the war, including the major cities and neighboring countries. From 1954 to 1976, the country had been divided at the 17th parallel into the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) and the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam).

War was nothing new to the battle-torn Asian nation of Vietnam. It had been raging there for most of the countrys history. Prior to World War II, before there even was a Vietnam, fighting there was widespread. The three countries that would eventually make up VietnamTonkin and Annam in the north and Cochin China in the southhad been warring over boundary disputes for decades.

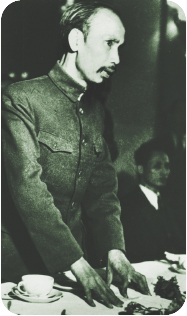

Finally, in 1945, a well-armed group of Indochinese, known as the Vietminh and led by a Soviet-trained Communist named Ho Chi Minh, forced the Annamese emperor Bao Dai off the throne. The group promptly claimed all three countries as its own. Ho Chi Minh was made president of the new country, which was renamed the Republic of Vietnam.

Image Credit: National Archives and Records Administration

Ho Chi Minh, the Communist leader of North Vietnam, in 1954.

But British forces in Cochin China, reinforced by French troops in October 1945, soon drove the Vietminh out of the south. The following June, France claimed Cochin China as a republic of the French Union, naming Bao Dai as chief of state. Soon, fighting broke out between French and Vietminh forces. Communist China, the Soviet Union, and other Communist countries supported Ho Chi Minhs Vietminh troops from the north. On the other side, Great Britain, the United States, and several other democratic countries supported Bao Dais new government in the south. Meanwhile, Dai appointed Ngo Dinh Diem his new premier.

After nearly a decade of civil war, the fighting between the north and the south finally came to a halt on July 21, 1954. Following a long and complicated peace conference held in Geneva, Switzerland, an imaginary line was drawn across Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh would control the government in the north, and Bao Dai would retain control of the government in the south. The Geneva Accords also called for national elections to unite the two governments into one country. But when South Vietnam rejected North Vietnams proposals to arrange for the elections, fighting once again broke out between the two nations.

Image Credit: U.S. Department of Defense

French troops question a man suspected of being a member of the Vietminh in 1954.

By the end of his term of office in 1961, U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower was becoming increasingly concerned about the escalating war in Vietnam. He had received several classified military documents detailing the Soviet Unions military involvement in the country of Laos, which neighbors Vietnam. A small, well-armed group of North Vietnamese troops, called Vietcong, slowly began infiltrating South Vietnam. The group was using its bases in Laos to stage attacks against the government of South Vietnam. The Vietcongs goal was to win the support of the people, overthrow the government of Diem, and unite South Vietnam with North Vietnam under Communist rule. And it seemed as though the Vietcong were winning. Unless the United States acted to stop the North Vietnamese, all of Southeast Asia might soon fall to Communism. At least that was the theory.

When John F. Kennedy won the presidential election in 1960, he met with outgoing President Eisenhower for a briefing on the war in Vietnam. At Eisenhowers suggestion, Kennedy agreed to send additional U.S. advisers and increase economic aid to South Vietnam to help the democratic governmentnow headed by Diemdefeat the North Vietnamese forces.

Image Credit: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

President Dwight D. Eisenhower shakes hands with South Vietnams leader Ngo Dinh Diem at the Washington National Airport in 1957. The United States supported Diems democratic government and wanted to stop Ho Chi Minhs communism from spreading.

But despite increased U.S. aid, the Vietcong continued their advances, slowly winning control of many of the small towns that dotted the South Vietnamese countryside. In order to stop the spread of Communism, Kennedy had to stop the Vietcong. In a speech to the American people early in 1961, Kennedy called Vietnam a proving ground for democracy and a test of American responsibility and determination. Few Americans at the time had even heard of Vietnam, and fewer still cared about what was happening there.

Following his speech, the president called his closest advisers to a meeting to discuss the growing Vietnamese problem. Half of the advisers suggested that the United States continue sending Diem aid. The other half wanted the president to send U.S. combat troops to help in the fighting. Kennedy himself was not prepared to abandon Vietnam to Communist forces. But neither was he ready to commit American troops to a war halfway around the world. Besides, Congress would never authorize such an ambitious military venture, and he might not win support for the plan from the American people.

So in April 1961, Kennedy created a special task force to provide social, economic, political, and military aid to the South Vietnamese government. He agreed to support the strengthening of South Vietnams army of one hundred and fifty thousand soldiers with an additional twenty thousand men. He also agreed to send an additional one hundred American military advisers to Vietnam, bringing the total number of Americans in that country to eight hundred.

Image Credit: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration

An armed member of the Vietcong crouches down inside a bunker in 1968. The Vietcong were guerilla soldiers, which meant that they were not part of the regular army and did not fight according to the rules of war.

The following month, Kennedy asked Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson to go on a fact-finding mission to Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam. There, after meeting with President Diem, Johnson learned just how serious the war was. Upon his return to America, the vice presidentwho opposed the spread of Communism as much as Kennedy didannounced that the loss of Vietnam to the Communists would one day force America to fight on the beaches of Waikiki [Hawaii].