Published in 2021 by New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2021 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2021 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Caroline Que: Editorial Director, Book Development

Cecilia Bohan: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Greg Tucker: Creative Director

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Police in America: inspecting the power of the badge / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York: New York Times Educational Publishing, 2021. | Series: In the headlines | Includes glossary and index. Identifiers: ISBN 9781642823271 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642823264 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642823288 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: PoliceUnited StatesJuvenile literature. | Law enforcementUnited StatesJuvenile literature. | Police brutalityUnited StatesJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC HV8139.P655 2021 | DDC 363.230973dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

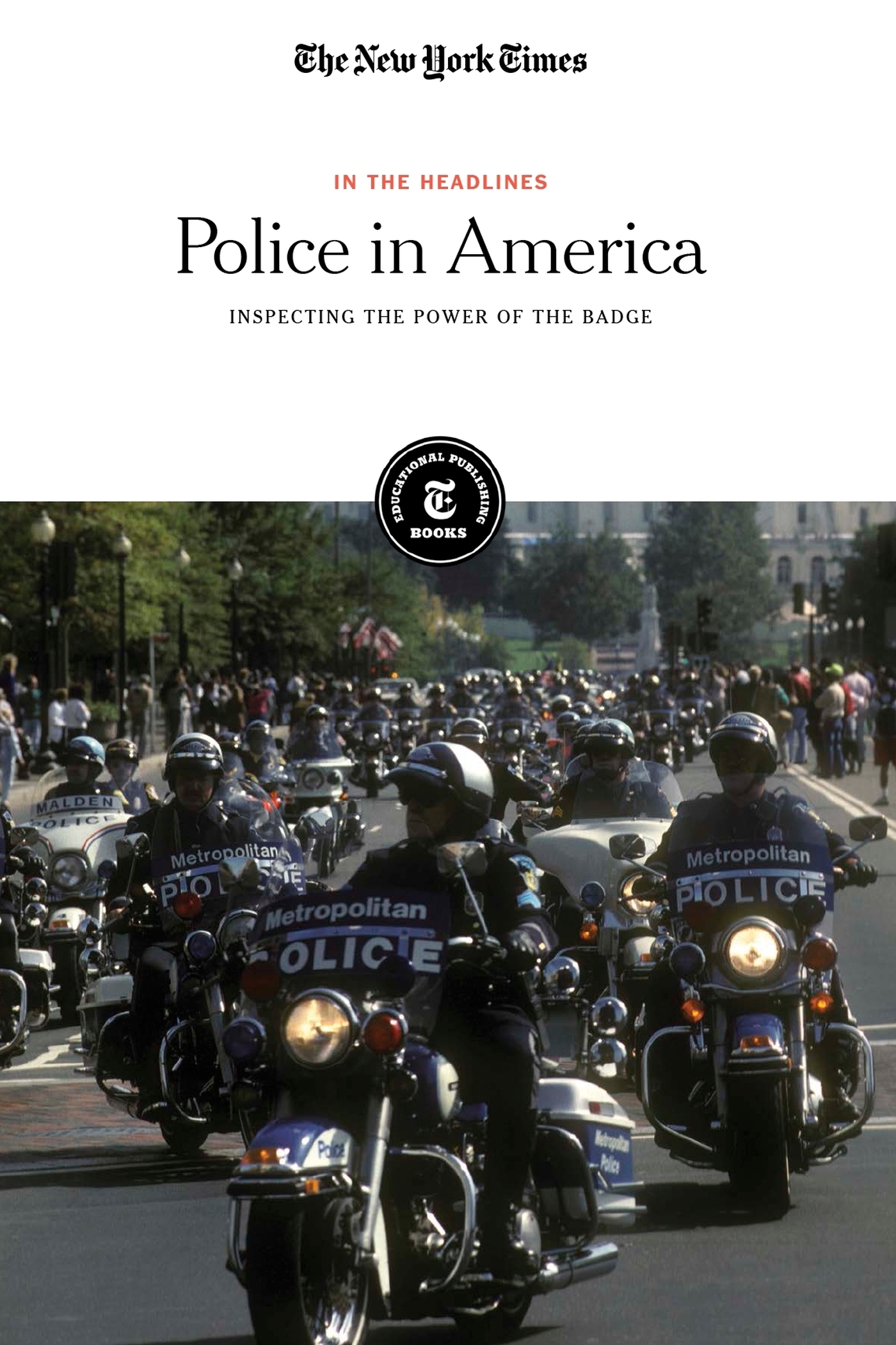

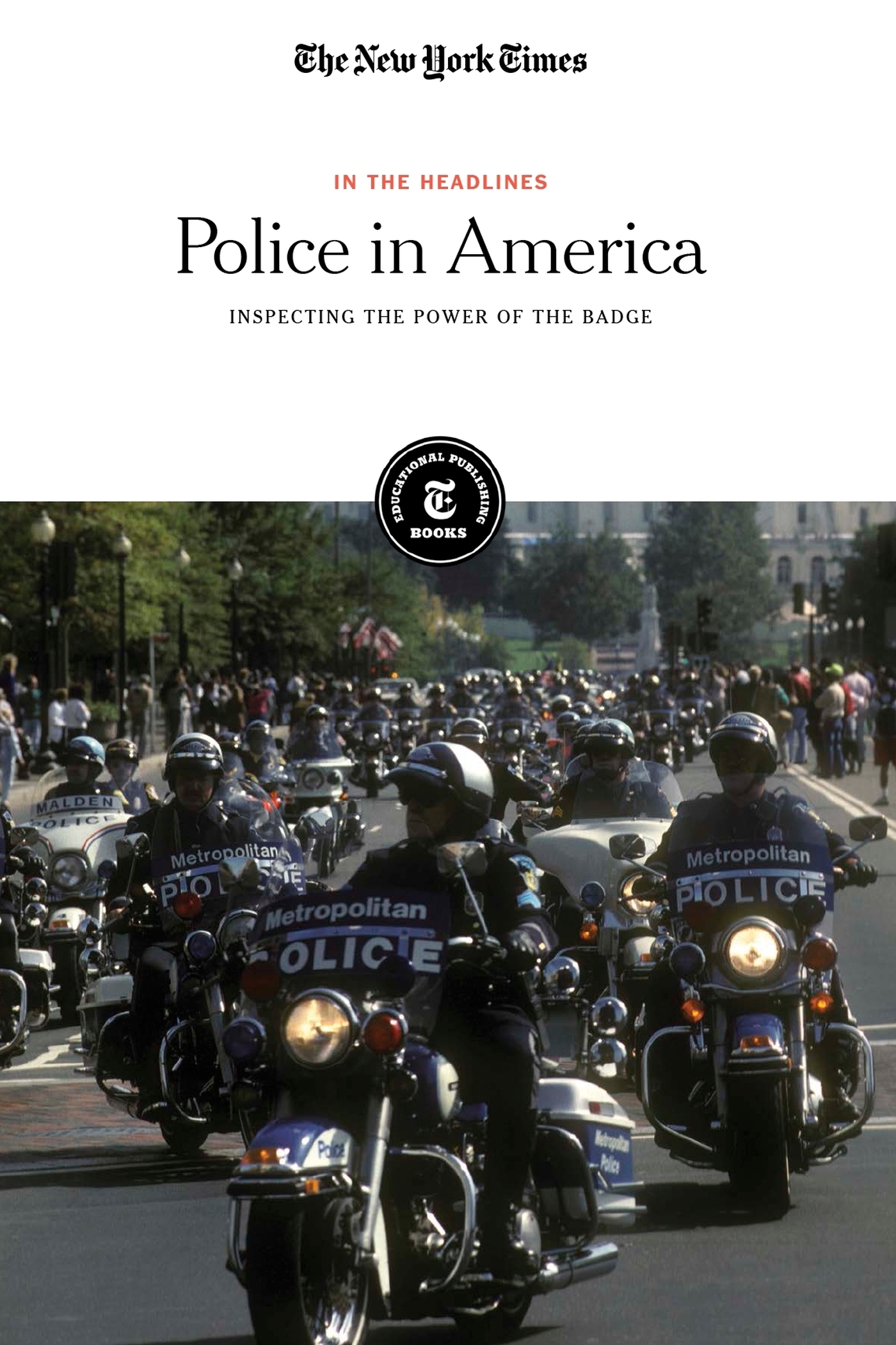

On the cover: Metropolitan police in formation during a Columbus Day procession, Washington, D.C.; Vincent Fournier/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images.

Contents

Introduction

THE MISSION STATEMENT of the New York City Police Department, the largest police force in the United States, reads: The mission of the New York City Police Department is to enhance the quality of life in New York City by working in partnership with the community to enforce the law, preserve peace, protect the people, reduce fear, and maintain order. Perhaps the most crucial phrase in this mission statement is working in partnership with the community: If the police are disconnected from the communities they are meant to serve and protect, how effectively can they accomplish their goals?

This is the underlying question that drives much of the analysis of police conduct in the United States, and it is something police forces across the country continue to grapple with. Efforts to incorporate community policing assigning officers to work regularly in a specific area so they form a rapport with the local community have had mixed results in different regions. This approach is especially necessary in high-crime communities, as trust and communication between police and civilians may make a significant difference in reducing crime in those areas.

Its worth noting that increasing the amount of time specific officers spend in a community is not the same as increasing police presence in that community altogether. Increased police presence in a community that distrusts the police might elevate tensions, particularly in minority communities. In such cases, as journalist Tina Rosenberg writes, it is important in itself to reduce the sense that police are an army of occupation. Given the historically fraught relationship between police and minority citizens, accomplishing this is no easy feat. So what can police forces do to build trust with the public?

JOSHUA LOTT FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Police officers watch demonstrators block Interstate-94 as they protest the fatal police shooting of Philando Castile in St. Paul, Minn., on July 9, 2016.

To answer this question, police are tasked with examining the structural bias, racism and use of force that pervades American law enforcement. One of the major obstacles in reckoning with these issues is that evidence of these problems is often not well-tracked or such incidents are dismissed as one-offs that are not representative of the police as a whole.

Even so, efforts at police reform persist. Law enforcement leaders have proposed changing training methods to prioritize de-escalation tactics before resorting to force. The expansion of tech tools at officers disposal, from tracking information to facial recognition software to surveillance drones, has the potential to better prepare police to handle specific situations more safely. However, lack of government resources or support can impede the changes law enforcement officers push for, and the flaws of certain tech tools raise concerns about privacy and racial bias.

As all of these issues persist on the larger scale, individual tragedies of deadly force continue to occur. The unnecessary killings of black citizens and police officers alike are reported with alarming frequency, leaving civil rights organizations, victims families and individual officers searching for justice. How can instances of police abuse and deadly force be addressed so the loved ones of victims can heal? What is the process of trying to enact real change within a police force so that these incidents can be prevented from happening again? The following articles chronicle efforts across the country to answer these questions, and to determine what police need to protect and serve as well as what communities need from law enforcement.

CHAPTER 1

Police and the Community: Connecting, Serving and Protecting

Specifying the role of the police in a given area is no easy feat. Every community has distinct needs and requires a custom approach to service-related activities, maintaining order and curbing crime. This chapter details some of the strategies police have used in different areas, as well as assesses the basic history of the police, from the nine principles of policing to bringing women onto the force.

Tensions regarding race relations, police presence and the freedom to criticize police practices are also explored.

The Point of Order

ESSAY | BY NICK PINTO | JAN. 13, 2015

THE QUESTION OF whom the police serve, and whose order they impose, is once again up for debate. But it is as old as policing itself. A political cartoon by Charles Jameson Grant, sold for a penny or two on the streets of London around 1834, depicts the British secretary of state addressing members of Londons recently formed Metropolitan Police Force. My lads, he says, you are always justified in breaking the heads of the public when you consider it absolutely necessary for the maintenance of the public peace. The assembled constables, a rough-looking crew, appear perfectly capable of such a task. By Jasus I wish your honor would give us a few throats to cut, one says, for we have had enough of breaking heads.

Just about five years old at the time, the Metropolitan Police had already earned a handful of unflattering nicknames, as noted in the cartoons title: Reviewing the Blue Devils, Alias the Raw Lobsters, Alias the Bludgeon Men. Britains soldiers were colloquially known as lobsters, because they wore red coats, so in an effort to quiet fears that the police would be a kind of occupying army, the Metropolitan Police wore blue instead. Many early opponents of the police suspected that the difference was only cosmetic; they worried that it would take only a little hot water for the men in blue to show their true color.

London in the early 19th century was a sprawling and disorderly metropolis, divided into scores of parishes, each responsible for hiring its own night watchmen and constables. In cases of great civil disturbance, order was restored by the army. In 1829, after years of opposition, the home secretary, Sir Robert Peel, finally persuaded Parliament to institute a professional police force in the rapidly growing areas around the capital. Skeptics saw the police as a tyrannical import from the Continent; Paris, Vienna, Berlin and St. Petersburg had already created local police forces, and they were regarded as agents of state oppression. To address these criticisms, Peel took pains to distinguish his nascent police and demonstrate that the Met would be answerable to the people, not the king or private interests. Not only would they wear blue, but, like many ordinary citizens, they would also sport top hats. And they would not, except in rare circumstances, carry firearms.

Next page