Published in 2021 by New York Times Educational Publishing

in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2021 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2021 The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Caroline Que: Editorial Director, Book Development

Phyllis Collazo: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Alexander Pappas: Editor

Greg Tucker: Creative Director

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

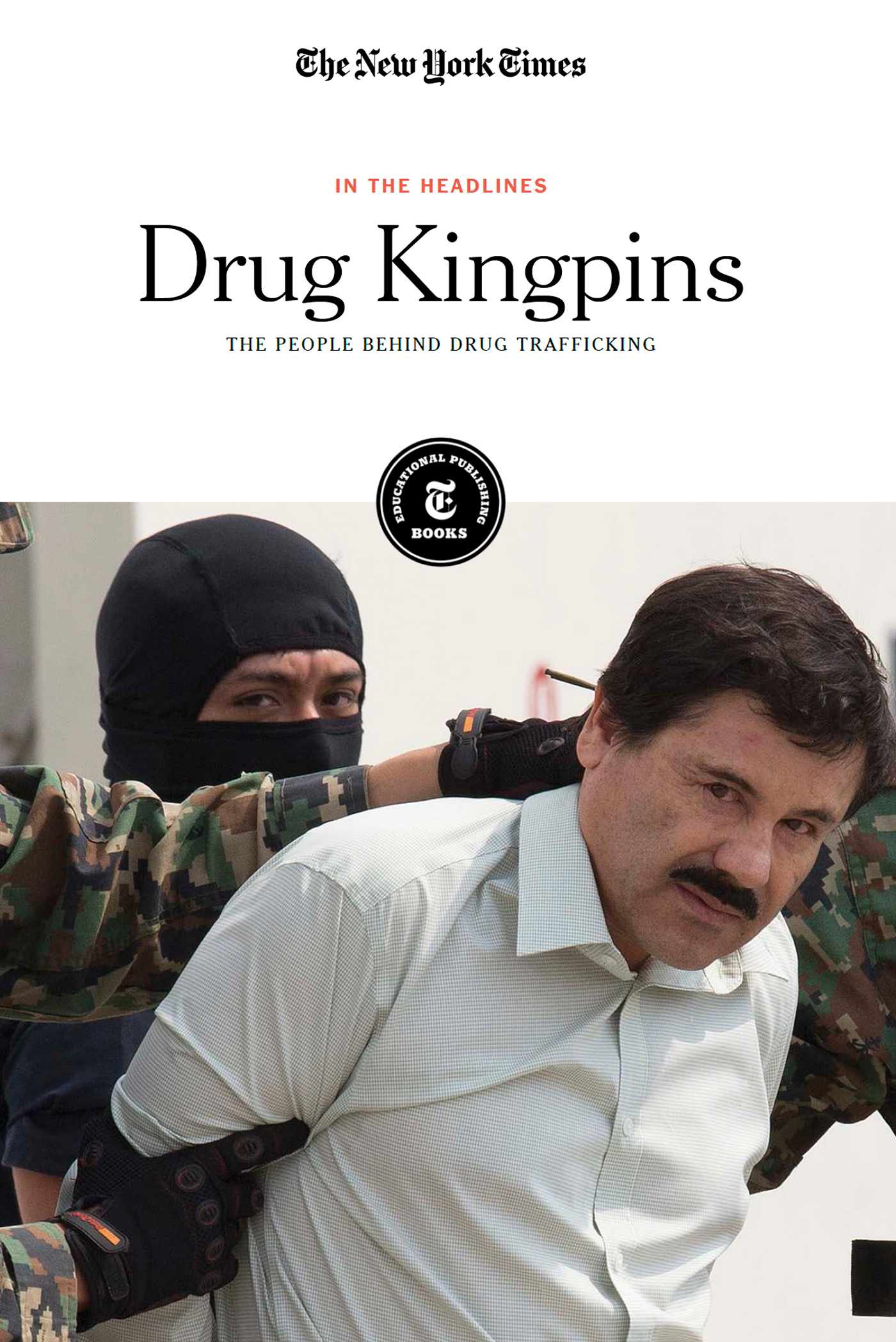

Title: Drug kingpins: the people behind drug trafficking / edited by the New York Times editorial staff.

Description: New York: New York Times Educational Publishing, 2021. | Series: In the headlines | Includes glossary and index. Identifiers: ISBN 9781642823394 (library bound) | ISBN 9781642823387 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642823400 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Drug trafficJuvenile literature. | Drug dealers Juvenile literature. | Drug controlJuvenile literature. Classification: LCC HV5809.5 D784 2021 | DDC 363.45dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

On the cover: Drug kingpin Joaqun El Chapo Guzmn is escorted to a helicopter by security forces at Mexico City International Airport, Feb. 22, 2014; Susana Gonzalez/Bloomberg/Getty Images.

Contents

Introduction

NARCOTICS HAVE A LONG and complicated history. They have at times been deemed lawful, and at other times, considered illicit contraband. Some former illegal opiates, for instance, are now employed for medical purposes; however, not all narcotics have beneficial qualities. Indeed, some take a devastating toll. In the modern era, drugs such as heroin, cocaine, ecstasy and methamphetamine conjure the darkest images of violence and addiction.

These sinister connotations are well-earned. In Mexico, drug cartels and the kingpins who lead them play such a prevalent role that they directly impact every level of local and national government. While in the United States our perspective can be myopic, other countries continue to struggle against the current of the global drug trade. In the Philippines, President Rodrigo Duterte has launched a ruthless, extra-judicial military campaign to oust powerful drug cartels. In Colombia, the unofficial capital and chief exporter of cocaine, drug cartels held the country at ransom politically and economically for most of the late 20th century. In Afghanistan, American troops and national guards have been unable to contain the popular resurgence of an old face: opium.

The leaders of these narcotrafficking businesses are commonly known as drug kingpins. While they deal primarily in narcotics, drug kingpins rsums commonly include terrorism, human trafficking, political assassinations and fomenting violent civil unrest.

Some have had even more unique abilities that have allowed them to expand their power: Frank Lucas was able to exploit the political upheaval of the Vietnam War to his advantage. By negotiating with corrupt U.S. military officials based in Vietnam and Thailand, Lucas was able to smuggle narcotics directly from the Golden Triangle into Harlem, using the coffins of deceased servicemen to avoid detection. Paul Le Roux was able to fully utilize digital technology to remain anonymous and expand his control over global heroin trafficking. Le Roux initially funded his empire by identifying the niche market of low-cost prescription pharmaceuticals in the United States and fostering a legitimate business. Others, like El Chapo, were able to play upon local loyalties of corrupt government officials and preexisting animosities to consolidate his power. Through his charisma and network, El Chapo nearly monopolized all drug trafficking across the Mexican border with the United States.

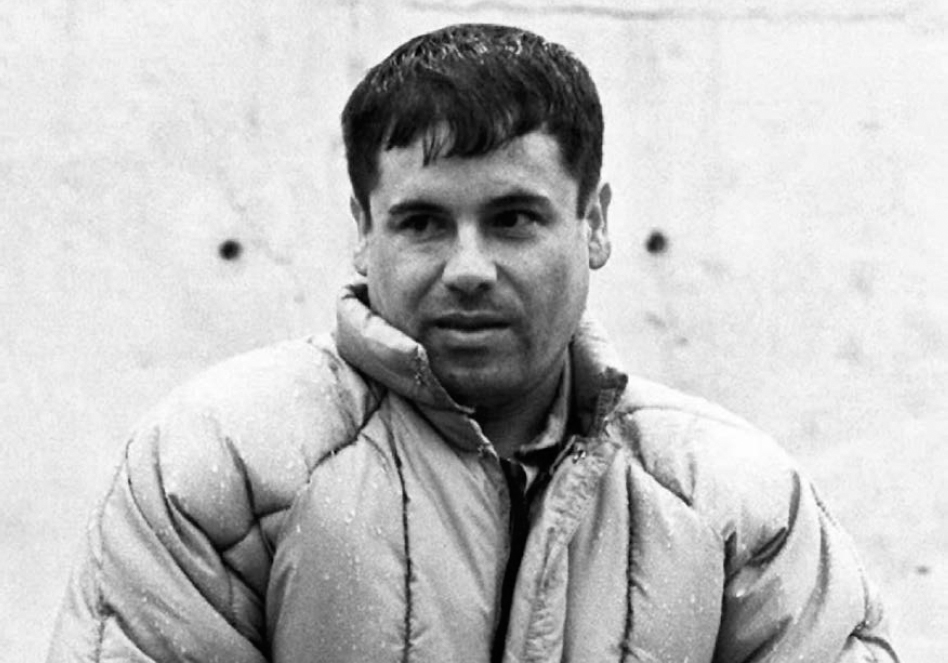

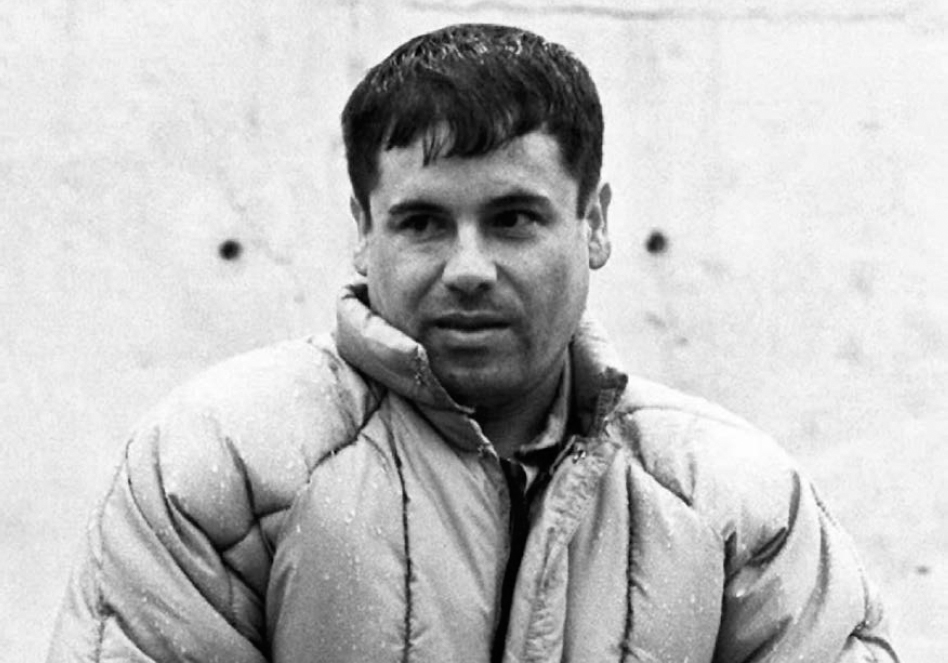

STR/STRINGER/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Joaqun Archivaldo Guzmn Loera, more famously known as El Chapo, at La Palma prison in Almoloya de Jurez, Mexico, in July 1993.

No other drug kingpin has yet to surpass the legacy of Pablo Escobar. At times magnetic, egotistical and audacious, Escobar exploited the political turmoil that plagued Colombia during the 1980s to solidify his control over the Medelln cartel and the countrys cocaine trade. By funding left-wing terrorist groups, killing his enemies and sponsoring attempts at regime change, Escobar was able to set rival forces against one another to his advantage.

While some may romanticize kingpins such as El Chapo and Pablo Escobar into counterculture figureheads, it is important to fully understand the breadth of their crimes: the bombing of civilian targets; the execution of politicians and law enforcement officials; the assassination of witnesses and their families. Then there is the larger human cost: Thousands of men, women and children in the United States perish every year as a direct result of drug addiction. In Bogot, for every fond memory of Escobars philanthropy toward the citys poor, there are many more recollections of the countless public bombings in the same city carried out by the Medelln cartel. Drug kingpins leave an indelible mark on the communities they use for narcotrafficking, and their far-reaching impact can take years to undo by even the most vigilant law enforcement efforts.

CHAPTER 1

The Crimes of El Chapo

When one considers the illicit world of drugs today, the most notorious name is El Chapo. The life of Joaqun Archivaldo Guzmn Loera is well-documented in his native Mexico, and in the rest of North America his reputation has afforded him celebrity-like status. His many escapes from Mexican prisons read like Wild-West myths. As the leader of the Sinaloa cartel, El Chapo ordered the deaths of his rivals. Indeed, El Chapo was a household name long before he was convicted in Brooklyn for drug trafficking and murder.

Searching for El Chapo From the Sports Desk

TIMES INSIDER | BY RANDY ARCHIBOLD | JULY 15, 2015

Times Insider delivers behind-the-scenes insights into how news, features and opinion come together at The New York Times.

FROM MY DESK, I caught snippets of conversation that affect my new job as deputy sports editor in The Timess New York office. A columnist discussed plans for a future column with an editor; off in the distance, the name of retired baseball commissioner Bud Selig hung in the air after being uttered in another conservation. On a big-screen television tuned to ESPN, something about Dez Bryant and a contract flicked by.

But my focus was far afield my first day on the new job, which I began Monday after five years as the bureau chief for Mexico, Central America and the Caribbean.

The phone rang. It was my former editor Greg Winter, on the international desk. He wanted to talk about Joaqun Guzmn Loera, the infamous Mexican drug lord better known as El Chapo, who had escaped last weekend in made-for-TV-movie fashion through a tunnel bored under the countrys most secure prison.

It is common for correspondents to switch jobs after several years in the field. Changing jobs, not to mention moving from one country to another, often comes with its share of bumps. One is the possibility of breaking news yanking you back to your old job.

As a friend jokingly said, You can check out, but you can never leave.

Next page