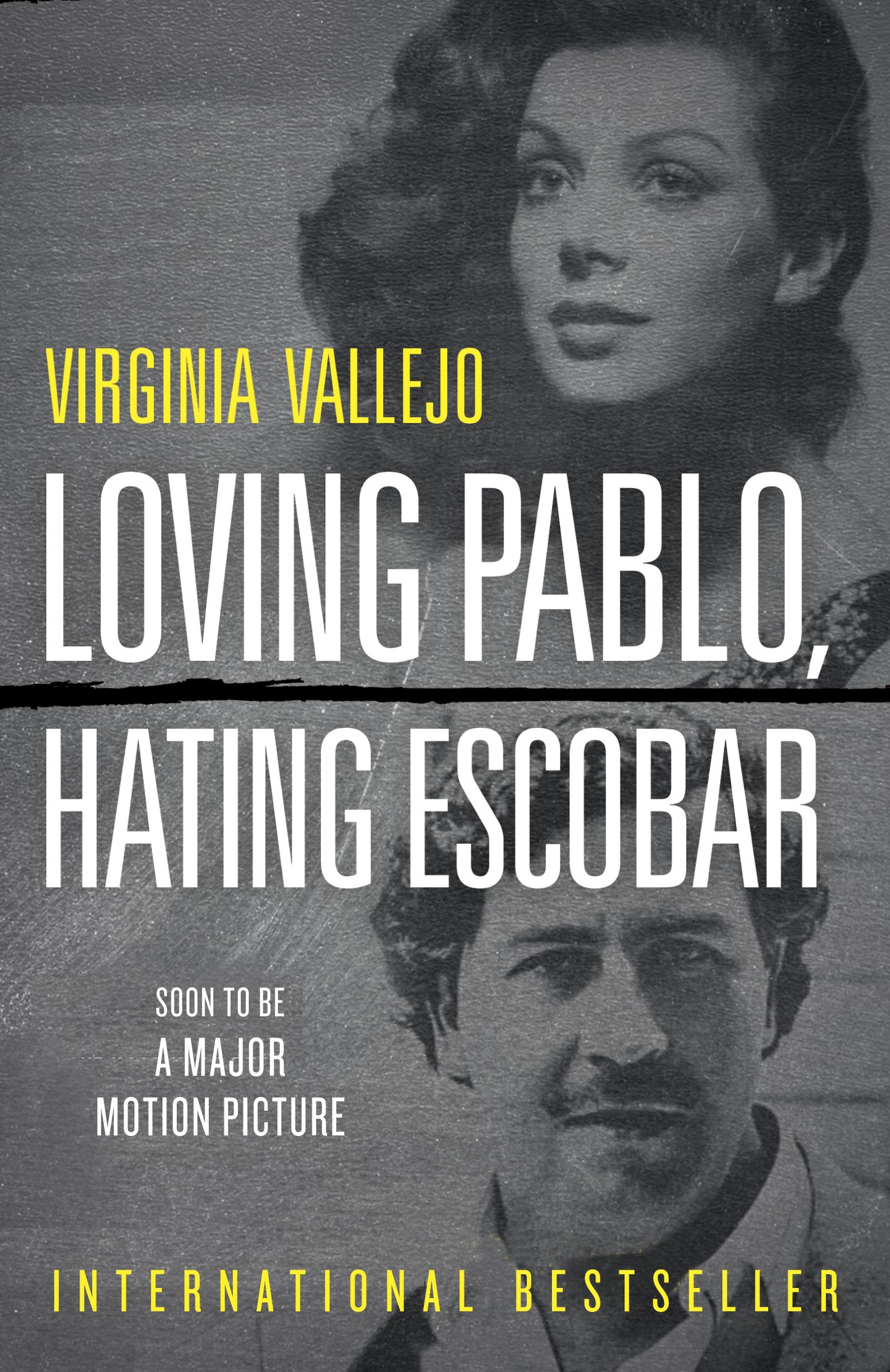

Virginia Vallejo

LOVING PABLO, HATING ESCOBAR

Virginia Vallejo was the most important Colombian radio anchorwoman and television presenter in the late 1970s and 80s. In 1982, she met Pablo Escobar, head of the Medelln Cartel. In 1983, they began a romantic relationship that ended in 1987, six years before his death.

In July 2006, she offered her testimony against a former justice minister on trial for conspiring with Escobar in the assassination of a presidential candidate. That same month, the DEA took her out of Colombia, on a special flight to save her life, so she could testify in other leading criminal cases.

Originally published in 2007 by Random House Mondadori, Amando a Pablo, Odiando a Escobar (Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar) became a number one international bestseller in Spanish. Due to brutal attacks and threats from the Colombian government, paramilitary, and media, she received political asylum from the United States in 2010. She continues to live in Miami, where she is writing two more books.

A VINTAGE BOOKS ORIGINAL, MAY 2018

English translation copyright 2018 by Megan McDowell

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York. Originally published in Mexico as Amando a Pablo, Odiando a Escobar by Random House Mondadori, S.A., de C.V., Mexico, D.F., in 2007. Copyright 2007 by Virginia Vallejo.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

All photographs courtesy of the authors private collection.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file at the Library of Congress.

Vintage Books Trade Paperback ISBN9780525433385

eBook ISBN9780525433408

Cover design by Christopher Gale

Cover photographs: Virginia Vallejo Hernn Daz; Pablo Escobar Eric Vandeville/ Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

www.vintagebooks.com

v5.3.1

ep

To my Dead,

to the heroes and the villains.

We are all one,

one single nation,

just one atom

recycled infinitely

always and forever.

Contents

Introduction

IT IS SIX IN THE MORNING on July 18, 2006. Three bulletproof cars from the American Embassy pick me up from my mothers apartment in Bogot to drive me to the airport, where a plane headed to some place in the United States is waiting for me with its engines running. A vehicle with security personnel armed with machine guns precedes us at top speed, and another one is behind us. The night before, the embassys head of security had warned me that there were suspicious people at the other end of the park that the building overlooks, and he informed me that his mission was to protect me; I shouldnt get close to the windows for any reason or open the door to anyone. Another car with my most precious possessions left one hour earlier; it belongs to Antonio Galn Sarmiento, president of the Bogot City Council and brother of Luis Carlos Galn, the presidential candidate assassinated in August 1989 under orders from Pablo Escobar Gaviria, head of the Medelln Cartel.

Escobar, my ex-lover, was shot to death on December 2, 1993. To bring him down after a hunt that lasted nearly a year and a half, it was necessary to offer a reward of twenty-five million dollars and to employ a Colombian police commando unit specially trained for the purpose, plus some eight thousand men from the state security organizations; the rival drug cartels and the paramilitary groups; dozens of agents from the DEA, the FBI, the CIA, the Navy SEALs, and U.S. Army Delta Force; and U.S. planes with special radar as well as money from some of the richest men in Colombia.

Two days earlier, in Miamis El Nuevo Herald, I had accused the ex-senator, exminister of justice, and former presidential candidate Alberto Santofimio Botero of instigating the murder of Luis Carlos Galn and of having built golden bridges between the bosses of the drug cartels and the presidents in Colombia. The Florida newspaper dedicated a fourth of the front page, plus a complete inside page, of Sundays paper to my story.

lvaro Uribe Vlez, who has just been reelected president of Colombia with more than 70 percent of the vote, is preparing to take his oath on August 7. After my offer to the nations attorney general to testify in the open case against Santofimio, which should have lasted for another two months, the judge has abruptly closed it. In protest, Colombias ex-president and ambassador to Washington has resigned, Uribe has had to cancel the naming of another ex-president as the new ambassador to France, and a new minister of foreign affairs has been named to replace the former, who went to occupy the embassy in Washington.

The United States government knows perfectly well that if they deny me their protection, I could well be killed in the coming days, because I am the only witness in the case against Santofimio. They also know that with me, the keys to some of the most horrendous crimes in Colombias recent history would also die, along with valuable information about the penetration of narco-trafficking into all the most powerful and untouchable levels of presidential, political, judicial, military, and media power.

Officials of the American Embassy are posted at the planes stairs; theyre there to carry up the suitcases and boxes I managed to pack in a few hours with help from a couple of friends. They look at me curiously, as though wondering why an exhausted-looking, middle-aged woman awakens so much interest in the media, and now also from their government. A DEA special agent six and a half feet tall, who identifies himself as David C. and sports a Hawaiian shirt, informs me that he has been tasked with escorting me to American territory. He also tells me that the bi-engine plane will take six hours to reach Guantnamo, and after an hour-long stop to fill up on fuel, two more to reach Miami.

I dont feel at ease until I see, safe in the back of the plane, two boxes containing evidence of the crimes committed in Colombia by the convicted felons Thomas and Dee Mower, owners of Neways International of Springville, Utah, a multinational company that I am facing in a lawsuit from 1998 worth thirty million dollars. Although in only eight days a U.S. judge has found the Mowers guilty of some of the crimes Ive spent eight years trying to prove before Colombian courts, all my offers to cooperate with Eileen OConnors office in the Justice Department in Washingtonplus five IRS attachs in the American Embassy in Bogothave blown up. Reacting furiously when they learned about my calls to the DOJ, the IRS, and the FBI, the embassys press office has sworn to block any attempt at communication with the government agencies of the United States.

The reason for their resistance has nothing to do with the Mowers and everything to do with Pablo Escobar: in the embassys Human Rights office works a former collaborator of Francisco Santos, the vice president of the republic, whose family owns the publishing house Casa Editorial El Tiempo. The media conglomerate occupies 25 percent of lvaro Uribes ministerial cabinet, which allows the company access to a gigantic cut of the state publicity budgetthe largest Colombian advertiseron the eve of El Tiempos sale to one of the main editorial groups in the Spanish-speaking world. Another member of the family, Juan Manuel Santos, has just been named minister of defense and tasked with renovating the Colombian Air Force fleet. So much State generosity for a single media family serves a purpose far beyond securing the countrys main newspapers unconditional support of Uribes government. It guarantees the newspapers absolute silence on the imperfect past of the president of the republic. Its a past that the United States government already knows about. I do too, and very well.