Published in 2021 by New York Times Educational Publishing in association with The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc.

29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010

Contains material from The New York Times and is reprinted by permission. Copyright 2021 The New York Times. All rights reserved.

Rosen Publishing materials copyright 2021 The Rosen

Publishing Group, Inc. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Publishing.

First Edition

The New York Times

Caroline Que: Editorial Director, Book Development

Cecilia Bohan: Photo Rights/Permissions Editor

Heidi Giovine: Administrative Manager

Rosen Publishing

Megan Kellerman: Managing Editor

Julia Bosson: Editor

Brian Garvey: Art Director

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: New York Times Company.

Title: Seeking asylum: the human cost / edited by the New York

Times editorial staff.

Description: New York: New York Times Educational Publishing, 2021. | Series: In the headlines | Includes glossary and index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781642824186 (library bound) | ISBN

9781642824179 (pbk.) | ISBN 9781642824193 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: RefugeesUnited States. | RefugeesUnited StatesSocial conditions. | Asylum, Right ofUnited States.

Classification: LCC JV6601.S665 2021 | DDC 323.631dc23

Manufactured in the United States of America

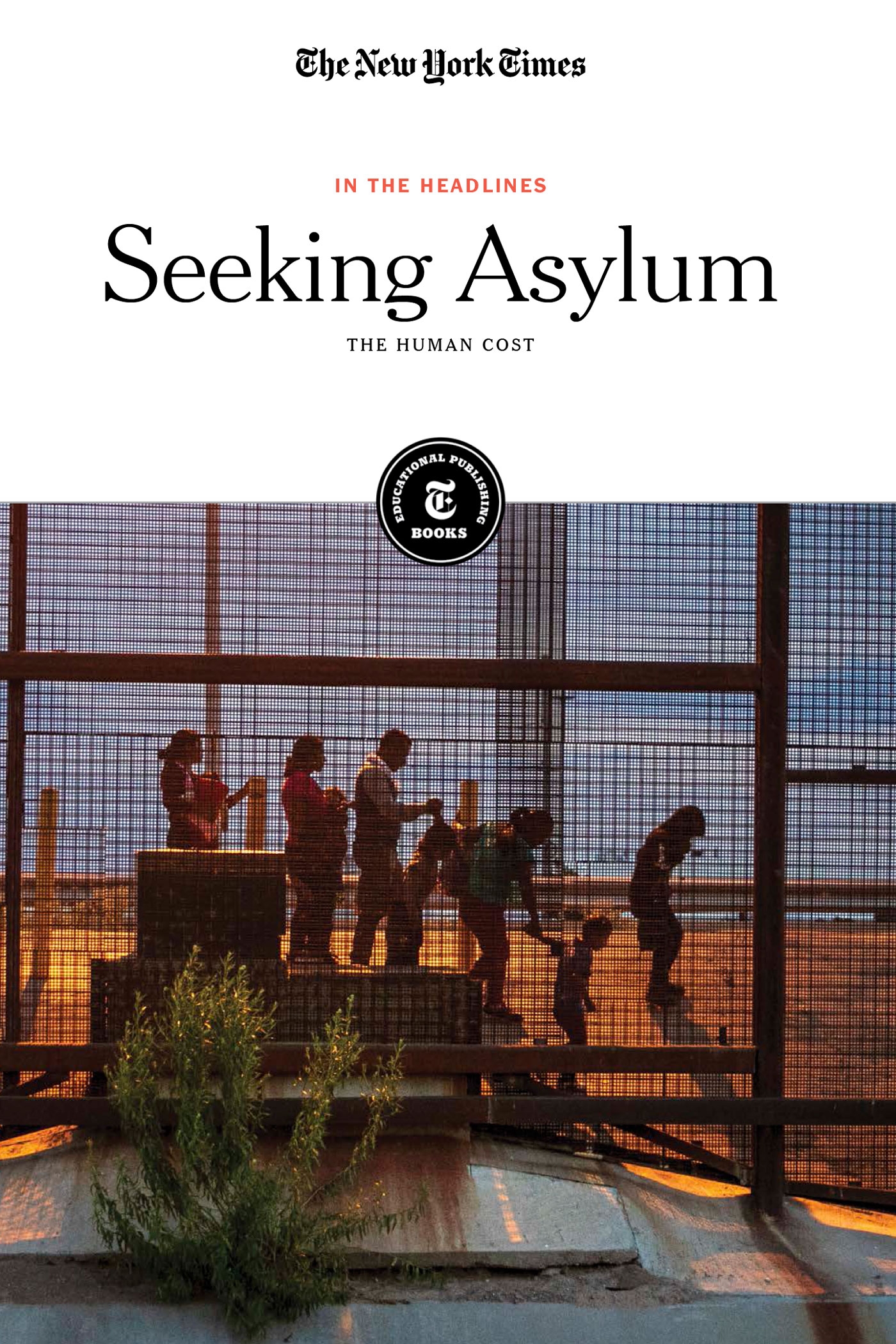

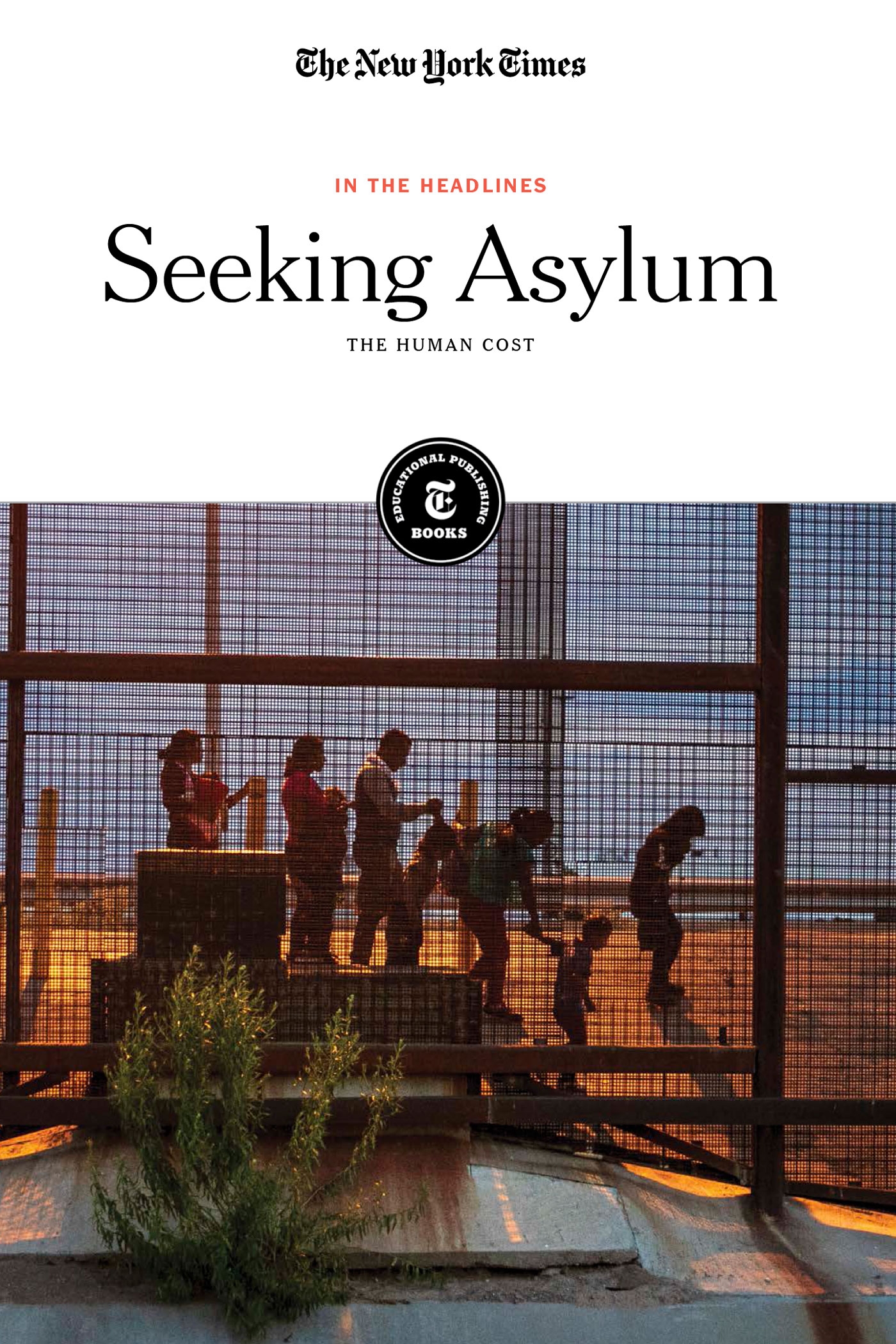

On the cover: Migrants from Guatemala walk along the Mexican side of the border, looking for an opportunity to enter the United States to seek asylum, in El Paso, Tex., on June 28, 2019; Ilana Panich-Linsman for The New York Times.

Contents

Introduction

IN JUNE 2019, a photographer took an image of the bodies of a Salvadoran man, scar Alberto Martnez Ramrez, and his twenty-three-month-old daughter, who had drowned trying to cross the Rio Grande into Texas. The gruesome photograph added fuel to a debate that has been increasing in intensity during the Trump administration: As record numbers of Central American men, women and children have been driven to seek refuge inside the United States, the path to asylum has become more narrow and perilous, leading to a humanitarian crisis on American borders.

The number of asylum seekers has only increased over the past several years: In the first half of 2019, more than 350,000 men, women and children from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras had been picked up by U.S. Border Patrol. There are as many stories of harrowing journeys as there are individuals seeking safety, but the contours of many stay the same: There are men who have refused to cooperate with drug cartels, families fleeing the wrath of violent gangs, and individuals hunting for refuge on the basis of being members of religious or L.G.B.T. minority groups.

Under standard U.S. policy, once individuals have made it into America, asylum seekers are granted temporary residential status as they enter a highly complex legal process that, with a backlog of several hundred thousand cases, can take years to be settled one way or another. They work with judges, advocates, social workers and lawyers in order to have their story heard and tried. In order to pass muster, their reasons for seeking asylum must fit a highly specific set of criteria: Even the slightest variation can cause an otherwise unimpeachable case to be rejected.

JOHN FRANCIS PETERS FOR THE NEW YORK TIMES

Asylum seeker Selvin Alvarado, 29, with his son at a shelter in the border city of Tijuana, Mexico, March 22, 2019. Alvarado says he is considering sneaking into the United States if his asylum claim is further delayed.

The asylum system has been under stress for more than a decade, but it saw new levels of challenge with the ascendancy of Donald J. Trump. Trumps 2016 presidential platform was largely centered around increasing border security and tightening asylum laws. And in the early years of his administration, he made good on his promise to restrict access to Americas heartland. His Departments of Justice and Homeland Security have restricted American asylum policy, narrowing both what can be considered grounds for asylum as well as complicating the steps necessary to receive asylum in the United States.

One strategy this administration has taken is the unprecedented act of preventing asylum seekers from entering the United States in the first place. In a law passed in 2019, the Trump administration ruled that individuals on their way to the United States must seek asylum in the first country they enter, meaning that most Central Americans who attempt to reach the United States through Mexico are legally required to request refuge there. Later the same year, Trump reached asylum deals with El Salvador and Guatemala, sending asylum seekers to await legal processes there.

For all intents and purposes, the United StatesMexico border has become closed to those who seek support and refuge in the United States, resulting in massive systems of poorly regulated camps and detention facilities. On the Mexican side, men, women and children wait with little sense of any political recourse and, increasingly, hope, vulnerable to the forces of traffickers and gang members who have made a habit of kidnapping asylum seekers for ransom. On the American side, families are experiencing the impact of Trumps family separation policy, which has resulted in detention facilities full of children without adequate food, protection or resources. The asylum process in the United States has become a compounded humanitarian crisis, exposing families who have already escaped the worst to further forms of danger and cruelty. If asylum means safety, then that is not what seekers will encounter. Instead, they find a system badly in need of reform.

CHAPTER 1

Understanding Asylum Policy

U.S. asylum policy changed drastically in the late 20th century. As political conflicts escalated in Central and South American countries, waves of asylum seekers appeared at the southern border, hoping for refuge. The United States has subsequently struggled to adjust, both adapting policy to offer more immediate help as well as narrowing the conditions for asylum when the sheer number of individuals increased dramatically.

In a Shift, U.S. Grants Asylum for Mexicans

BY SAM HOWE VERHOVEK | DEC. 1, 1995

HOUSTON, NOV. 30 The United States has quietly granted political asylum to at least 55 Mexican citizens in the last 14 months, a major shift after many years in which virtually all asylum applications from Mexicans were routinely rejected.

Immigrants-rights advocates hail these grants of asylum, which are made by individual Federal immigration agents and judges on a case-by-case basis, as a collective milestone that amounts to formal recognition by the United States that political repression occurs in Mexico. But the actions have created a growing diplomatic headache for the Clinton Administration by angering the Mexican Government and the ruling party that has dominated the country for more than 60 years.

The asylum approvals come during a time of huge increases in the numbers of such applications from Mexicans. Applications increased to 9,304 in the 1995 fiscal year, which ended Sept. 30, from 6,397 in 1993 and from only 122 in 1990. From 1990 through 1993, not a single asylum application was approved; in 1994 five were approved, and in the most recent fiscal year it was 54.

The cause of the increase is itself the subject of intense debate. Advocates for those seeking asylum say the increase reflects the Mexican publics growing opposition to the ruling political party and asylum applicants fears of retaliation for their political activities. But Federal immigration officials say that much of the increase represents fraudulent applications submitted by Mexicans seeking to take advantage of a loophole in the asylum law that allowed them to work legally in the United States pending review of an asylum request.

Next page