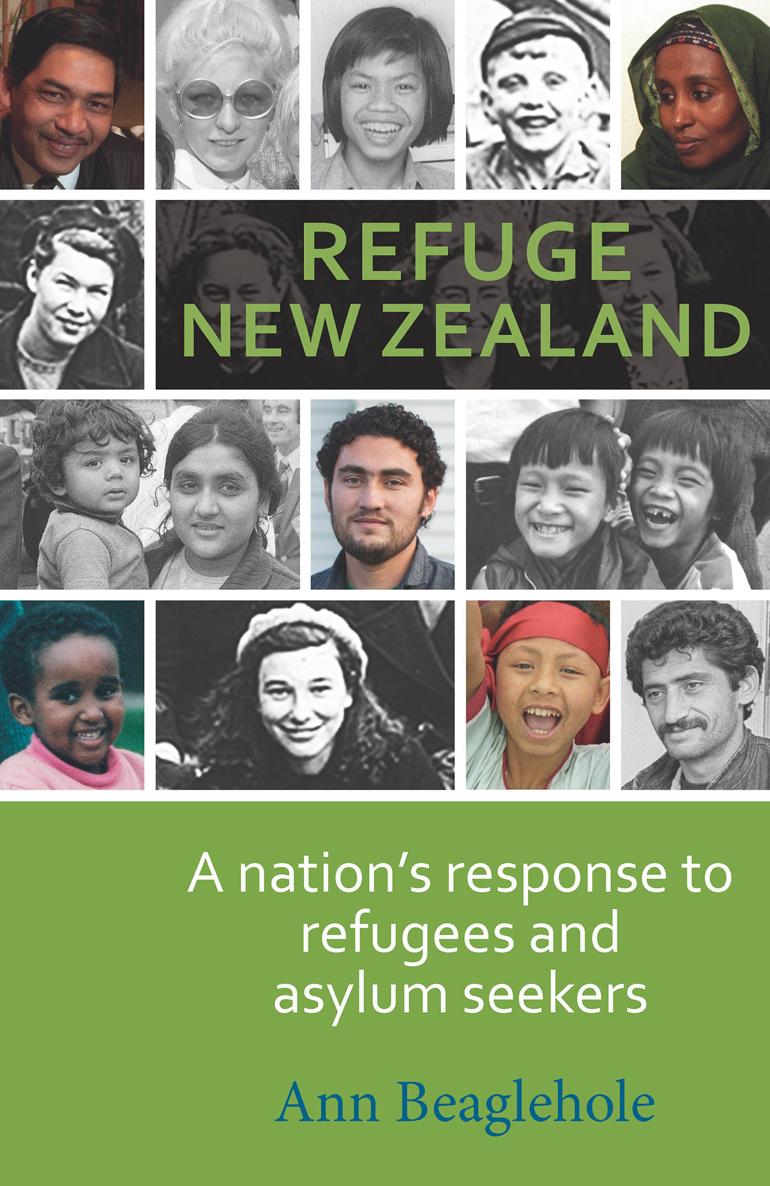

First published 2013

Text copyright Ann Beaglehole

Volume copyright Otago University Press

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

ISBN 978-1-877578-50-2 (print)

ISBN 978-1-927322-79-6 (Kindle)

ISBN 978-1-927322-80-2 (ePub)

ISBN 978-1-927322-81-9 (ePDF)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand. This book is copyright. Except for the purpose of fair review, no part may be stored or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including recording or storage in any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. No reproduction may be made, whether by photocopying or by any other means, unless a licence has been obtained from the publisher.

Publisher: Rachel Scott

Editor: Anna Rogers

Design/layout: Fiona Moffat

Index: Diane Lowther

Ebook conversion 2016 by meBooks

Contents

Acknowledgements

Many people have helped with the researching and writing of this book. I am grateful to the Waitangi Tribunal Unit, particularly to Richard Moorsom, who played a crucial part in arranging the leave that enabled me to write the first draft. My greatest debt is to Klaus Neumann, of Swinburne University of Technology, who instigated the project, obtained funding for it from the Australian Research Council and made useful comments on my early drafts. Without his collaboration the book could never have been written. I am most grateful to the Australian Research Council for their support. I am grateful too for the support of Swinburnes Institute for Social Research (now called The Swinburne Institute). Without the support of both the Institute for Social Research and Swinburne University the project would not have gone ahead. Thanks also to Tony Haas, who made helpful suggestions on an early draft, and to Anthony Hubbard for his comments. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade and the Department of Labour gave me permission to use their records. Thanks to Neil Robertson and Wendy Searle for their timely responses to my requests. I am also indebted to Lillian Loftus at the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of Victoria University of Wellington for administration support and Lydia Wevers at the Stout Research Centre for a space in which to work.

A number of people gave useful information. I would especially like to thank Mary Boyce, Peter Cotton, Lianne Dalziel, Roya Jazbani, Rachel Kidd, Don McKinnon, Aussie Malcolm, Dr Nagalingam Rasalingam, Theresa Sawicka-Brockie, Keith Taylor, Kevin Third and Conrad Wright. Colleagues at the Waitangi Tribunal Unit gave valuable feedback on the section of the book about Maori as refugees. The Asia 2000 Foundation pointed me on the right path regarding files associated with the project. Heartfelt thanks to Catherine Falconer-Gray who helped with the checking and the cutting of the manuscript. I would especially like to thank Joe Beaglehole, Malcolm McKinnon (as so often before), Steven Price and Teresa Shreves most sincerely for crucial advice and support. Thanks are also owed to staff at the Alexander Turnbull Library for their help with sourcing and ordering images and to the New Zealand Red Cross for permission to use their images. I am most grateful to Keith Taylor for the images he made available for the book from his archives.

A big thank you to Wendy Harrex of Otago University Press for helping to launch the book in a new direction, and to publisher Rachel Scott and editor Anna Rogers for their help in bringing the book to completion. Finally, I am grateful to David Beaglehole, who a few years ago said, Dont delay. Get on with your writing.

Ann Beaglehole

Introduction

Refugee and asylum seeker policies are controversial in many parts of the world, and New Zealand is no exception. Refuge New Zealand looks at the history of this countrys response to refugees and asylum seekers in order to shed light on its present refugee policy. It explores New Zealands unique approach to refugees and asylum seekers and tells the story of the involvement of the state and ordinary people in helping the victims of wars and conflicts by offering them a chance to start a new life.

Since 1944, when refugees were first distinguished from other migrants in official statistics, New Zealand has accepted more than 30,000 refugees.Which groups and categories have been chosen and why? Who has been kept out and why? How has public policy governing refugees and asylum seekers changed over time?

Unlike migrants who choose to migrate in search of new opportunities, refugees are forced to leave their homeland, typically to escape persecution because of their ethnicity, their religion or their political beliefs, or because they have been displaced by wars and other conflicts. Asylum seekers are people without United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR)-mandated refugee status; they seek to establish this after they have reached a country of asylum. Their claims are assessed under the 1951 United Nations Convention, the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees and other conventions relating to torture and civil and political rights.

These international agreements came about because, soon after the end of World War II, there was need for a general definition, replacing previous ad hoc agreements, of who was to be considered a refugee. The United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees was adopted on 28 July 1951. Signatories could stipulate that their commitment related only to people who had become refugees as a result of events taking place in Europe before 1951. The 1967 protocol made the 1951 provisions applicable to refugee situations after 1951 and worldwide. New Zealand is a signatory to both the convention and the protocol.

The 1951 convention defines a refugee as any person who:

owing to well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable, or owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country; or who, not having a nationality and being outside the country of his former habitual residence as a result of such events, is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to return to it

The distinction between migrants and refugees and between refugees and asylum seekers may become blurred at times. Members of the New Zealand public, especially those opposed to the arrival of dark-skinned strangers or people who chatter loudly in foreign languages, have not always differentiated between immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers. For the refugees themselves,

More than 60 years later, in New Zealand, Somali refugee Hassan Adam, a Muslim, expressed similar feelings. I never planned to be a refugee. It is a stigma, a title that goes with you for the rest of your life. Adam and his wife Fowzia Mohamed fled the war lords in Somalia, finding temporary refuge in Malaysia before coming to New Zealand. For seven years Adam was unable to find work in New Zealand that matched his skills. The label of refugee was a curse. For asylum seekers, however, refugee status is the sought-after passport to a new life, bringing the hope of permanent settlement in the country that has given them temporary asylum.