University of California Press

Oakland, California

2020 by Jana K. Lipman

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lipman, Jana K., author.

Title: In camps : Vietnamese refugees, asylum seekers, and repatriates / Jana K. Lipman.

Other titles: Critical refugee studies ; 1.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2020] | Series: Critical refugee studies ; 1 | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019052137 (print) | LCCN 2019052138 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520343658 (cloth) | ISBN 9780520343665 (paperback) | ISBN 9780520975064 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH : RefugeesVietnam20th century. | Refugee campsPolitical aspects20th century.

Classification: LCC HV 640.5. V 5 L 56 2020 (print) | LCC HV 640.5. V 5 (ebook) | DDC 362.87089/95922dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052137

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019052138

29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 21 20

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Introduction

IN SEPTEMBER 1975, A GROUP OF DETERMINED Vietnamese men participated in an elaborate and highly choreographed political demonstration in a U.S. refugee camp on Guam, a U.S. island territory in the Pacific. Four men volunteered to have their heads shaved in a public performance of dissent. A makeshift platform served as a stage. Two men sheared the hair off each protester. The men bowed their heads as their hair fell to the ground. Dozens of supporters surrounded the men and witnessed the scene. These activists wanted a ship so they could return to Vietnam under their own command. In the background, a banner proclaimed boldly in English, 36 Hours Hunger Sit-In. Quiet & Hair-Shaving Off to Pray for a Soon Repatriation.

With the collapse of South Vietnam in April 1975, more than 125,000 Vietnamese fled the country. The U.S. government directed them to Guam for initial processing, and the vast majority soon gained resettlement in the United States. However, these protesters were different. They had also evacuated South Vietnam in its chaotic last weeks, but once on Guam, approximately 2,000 of them realized they did not want to resettle in the United States. Some had spouses and children who had been left behind, others were elderly and feared an unknown future, and still more were young men in the South Vietnamese Navy who had been at sea when Saigon fell and whose ships simply never returned to port. Their protests unnerved U.S. officials, who had not anticipated that any Vietnamese would want to return to communist-controlled Vietnam. There was no plan for them. The would-be repatriates directed their message to the American, Guamanian, Vietnamese, and United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) officials who controlled their future, and they used every tool they could muster: letter writing, elected delegations, hunger strikes, sit-ins, marches, and even threats of violence. These men and women held their ground on Guam and insisted in no uncertain terms that they wanted to be repatriated. In a matter of months, they would succeed in forcing the hand of the United States, and most would choose to return to Vietnam.

FIGURE 1. Would-be repatriates have their heads shaved in an act of protest on Guam, 1975. Courtesy of the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, Record Group 319, Box 19, declassification number 984082.

Fast forward twenty years and turn to Palawan, an island within the Philippine archipelago with its own American colonial legacy. It too hosted a camp for Vietnamese men and women, from 1980 through 1996. During these years, approximately 40,000 Vietnamese transited through this camp, and most resettled in the United States. But not all. After 1989, not everyone gained de facto refugee status, and by 1996, approximately 2,000 Vietnamese who had been screened out remained in the camp. Most had been waiting there for more than five years, insisting that they were refugees and deserved resettlement in a country like the United States or Canada. The Philippines and the UNHCR disagreed. They had determined that these Vietnamese men and women had not produced evidence of political persecution, and therefore they were not refugees entitled to resettlement. By 1996, all screened out Vietnamese were slated for repatriation.

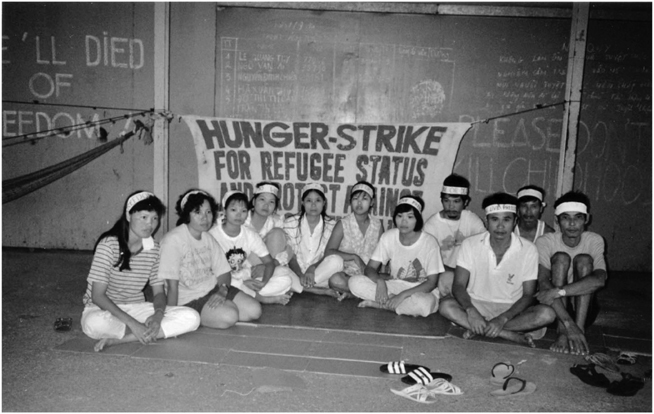

Like those on Guam before them, this group of Vietnamese took militant action. Over the course of the 1990s, the Vietnamese in Palawan engaged in hunger strikes, mass demonstrations, and acts of self-mutilation. There is an extensive documentary account of Vietnamese protesting within the camp with techniques that often looked remarkably like the earlier protests in 1975. In a striking 1993 photograph, a group of almost a dozen Vietnamese men and women solemnly protested inside the camp. They sat beneath a handmade sign: Hunger Strike for Refugee Status. Some of the hunger strikers looked directly at the camera, while others gazed away. The picture captured a melancholy moment, but the protest, including the decision to wear matching white headbands, was clearly organized and choreographed. However, in contrast to the repatriates on Guam, the Vietnamese in Palawan held the opposite goal: they rejected repatriation at all costs.

FIGURE 2. Vietnamese in Palawan protest the Comprehensive Plan of Action and plans for their repatriation, 1993. Courtesy of UC Irvine Libraries, Southeast Asian Archive, Project Ngoc Records.

When the Philippine government organized a forced repatriation flight in February 1996, the Vietnamese camp members physically attempted to block the runway where the plane was poised to take off. The camp abutted the provincial airport, and hundreds of Vietnamese men and women flooded the airfield. Individuals cried, prayed, and protested, with the goal of stopping the repatriations with their bodies. Armed Filipino soldiers responded to the protesters with water cannons and pushed hundreds of Vietnamese off the runway. They ensured the planes, with more than eighty Vietnamese on

These images remained with me long after I first encountered them. They were evidence of Vietnamese protest in the most unexpected of places, a refugee camp on Guam right after the collapse of Saigon and an island in the Philippines twenty years later, when most people were no longer thinking about refugees in Southeast Asia. The symmetry and disjunction between these stories have propelled my work on this book ever since.

After 1975, close to 800,000 individuals left Vietnam by boat, survived, and sought refuge in camps in Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Hong Kong. While interest in the Vietnamese escapes and camps waned in the United States, the politics of Vietnamese refugee status and resettlement remained front-page news in Malaysia, Hong Kong, and the Philippines throughout the 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and into the early twenty-first century.