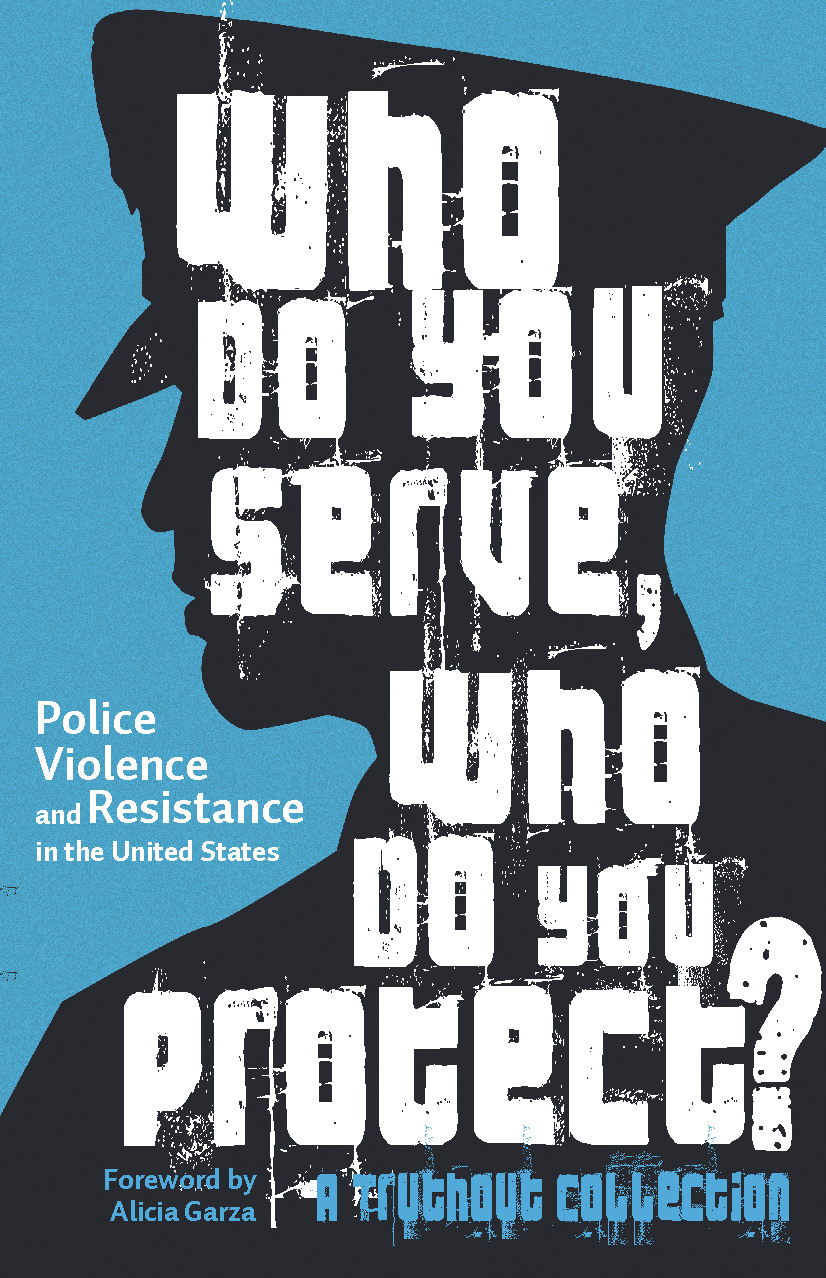

Praise for Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect?

This brilliant collection of essays, written by activists, journalists, community organizers and survivors of state violence, urgently confronts the criminalization, police violence and anti-Black racism that is plaguing urban communities. It is one of the most important books to emerge about these critical issues: passionately written, with a keen eye toward building a world free of the cruelty and violence of the carceral state.

Beth Richie, author of Arrested Justice: Black Women, Violence, and Americas Prison Nation

Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect? is a powerful collection of essays by organizers, legal activists and progressive journalists that takes us beyond the few bad apples theory of police violence, insisting that we interrogate the essential role and purpose of police and policing in our society. These writers have highlighted some of the critical questions that the anti-state-violence movement is wrestling with.

Barbara Ransby, author of Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision

This timely and essential set of essays written by activists, organizers and journalists offers a window into our particular historical moment centered on an ongoing struggle against state violence. As a long-time organizer immersed in the current Movement for Black Lives, I read the contributions hoping to learn and to be inspired. I found the essays to be informative, illuminating and challenging. The book covers topics ranging from police torture and the fight for accountability to how we might best engage in transformative organizing that could lead to a world without police. I cannot recommend this anthology any more highly. It's an indispensable primer for anyone who wants to understand the current rebellions and uprisings against police impunity.

Mariame Kaba, founder and director of Project NIA

Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect? is an extraordinary collection of writings by activists living and working at the epicenter of police violence and the anti-Blackness and structural racism so foundational to US systems of policing. Simultaneously enraging, invigorating, radically imaginative, practical and inspiring, this essential book relocates justice in accountable social, economic and cultural relationships, pointing the way toward foundational transformation rather than cosmetic reform.

Kay Whitlock, co-author of Considering Hate and Queer (In)Justice

America is at war, and the violence that propels that war is largely directed at people of color, especially Black youth. One instance of such a war is evident in the violence by the police against Black communities, the criminalization of everyday behavior, the assaults on Black bodies, and the ever-growing incarceration state. Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect? addresses this violence in a way no other book has done in the last forty years. It reveals the underlying causes, economic and ideological, that drive such violence so as to provide a comprehensive understanding of its roots, its multiple layers, history, and different forms, while at the same time it offers a discourse of critical engagement and transformation in order to address it. Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect? is an invaluable resource for asking questions about the emergence of racist violence and state terrorism as a defining principle of everyday life and how they can be addressed. Everyone who cares about justice and democracy and a future in which they mutually inform each other should read this book.

Henry Giroux, author of Disposable Futures: The Seduction of Violence in the Age of Spectacle

We know the names: Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, Freddie Gray, Eric Garner, Sandra Bland, Tamir Rice, Rekia Boyd, Laquan McDonald. And weve seen the uprisings: L.A., Ferguson, Baltimore, Chicago. Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect? goes behind the headlines to ask the deeper questions: Do the police make communities (particularly, communities where Black and Brown people live) safer? Who do community residents fear? Are there ways to address those fears without the police and carceral state? What would we have to create in order to do this? What steps must we take to get there? Each of the essays examines these interrelated questions in depth. Read together, they provide an extremely thorough, and timely, examination of the issues underlying these recent events, forcing us to rethink the very idea of justice in this country.

Alan Mills, Uptown People's Law Center

Resisting state-sanctioned violence, especially by police, has become a paramount issue as a result of grassroots activists mobilizing throughout the country. Who Do You Serve, Who Do You Protect? gives journalists, writers, and activists at the forefront of activism and reporting on state-sanctioned violence in the United States a welcome platform to present their ideas for growing a movement against this violence so activists may have a lasting impact, which empowers and lifts up communities of color.

Kevin Gosztola, managing editor of Shadowproof.com

Killing the Future: The Theft of Black Life

Nicholas Powers

Tell me of the night your son was killed by the police, I asked. She sat up, and a deep sorrow moved in her eyes. I had a habit of looking out the window to see my son, Danette Chavis said. But that night, I said to myself, Oh, leave the boy alone, and took a nap. The phone woke me up, and my daughter was rushing out of the door. I followed her and saw police tape, cops standing around a body. I yelled to see if it was him. But they wouldnt let me close. Later, I went to the morgue and identified my son.

We sat in the caf; a few seconds passed in silence. She looked away as if seeing him dead for the first time, and I regretted asking the question. Around us, people typed on laptops or chatted over coffee. They were so carefree. How do we reach a city that mostly looks at people of color in contempt or pity rather than solidarity? How do we get them to listen?

I looked up from my notebook. Ms. Chavis, I asked. What do you miss most about your son?

Making Wounds Speak

Imagine hearing that someone you love has died. Your heart would jump in your chest. Your body would clench like a fist around their memory. How angry would you be? How loud would you yell at the sky, at God, at anyone you could blame? Afterward, youd float in a limbo of grief until you got answers, made sense of it and then slowly said goodbye. Gathering together with others at the funeral, you could complete the storyline of loss.

The stages of grief depend on narrative closure, the shoveling of dirt on the casket, the eulogizing of the dead. But for African-American parents whose children were slain by law enforcement, the stages of grief grind to a halt. The dead cannot be laid to rest because the cop who murdered them is not held accountable, and the violence is condoned. To eclipse the officers guilt, the victims are niggerized in public. Have a criminal record? It will be paraded in public. Ever took silly gangsta photos? They will be proof of a thug life. The parents see their childs image warped as they learn of more Black and Latino youth killed by cops. In a solidarity of despair, they embrace everyones lost children, as if they can hear the dead repeating their final words, asking for their lives back.

In December 2014, 10 mothers whose children were killed by police held a rally in front of the US Department of Justice. Chavis was there and said into the megaphone, None of us are safe. Law enforcement around the United States is brutalizing, arresting and murdering. A large group surrounded her with signs and candles. One by one the mothers spoke. Some had fought for years, like Chavis, who started a petitionnow 35,000 signatures strongto send to former Attorney General Eric Holder, or like Valerie Bell, whose son Sean was shot dead by New York City Police Department (NYPD) officers in 2006. Other grieving parents were more recently bereaved, like Jeralynn Blueford, whose son Alan was gunned down by Oakland police in 2012. She stood in front of the rally, choking on tears, saying, Alans last words were, Why did you shoot me?