For Beginners LLC

155 Main Street, Suite 211

Danbury, CT 06810 USA

www.forbeginnersbooks.com

Copyright 2016 by Paul Von Blum

Illustrations Copyright 2016 by Frank Reynoso

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher.

A For Beginners Documentary Comic Book

Copyright 2016

Cataloging-in-Publication information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN # 978-1-9394389-89-8 Trade

Manufactured in the United States of America

For Beginners and Beginners Documentary Comic Books are published by For Beginners LLC.

First Edition

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

www.redwheelweiser.com

www.redwheelweiser.com/newsletter

contents

FOREWORD

BY PENIEL E. JOSEPH

The Civil Right Movement represents the most important social and political freedom movement in American history. Its origins date back to the period of antebellum slavery, when enslaved African found themselves in a world that considered them more a species of property than flesh and blood human beings with full citizenship rights.

African American political activism during the period of racial slavery challenged the framework of American democracy culminating in a Civil War (18611865) that abolished slavery and ushered in a new era of constitutional citizenship and (male) voting rights. The era of Reconstruction (18651877) witnessed an unprecedented flowering of black political and social organizing. African Americans joined political and social clubs, set up schools and churches, and ran for political office on a scale that would have been unimagined only several years before.

The march toward racial equality was halted, then reversed, by the brutal politics of white supremacy which used violence, racist laws, and legislative tricks to inaugurate a system of racial segregation, or Jim Crow, that continues to persist, in some form, until the present day.

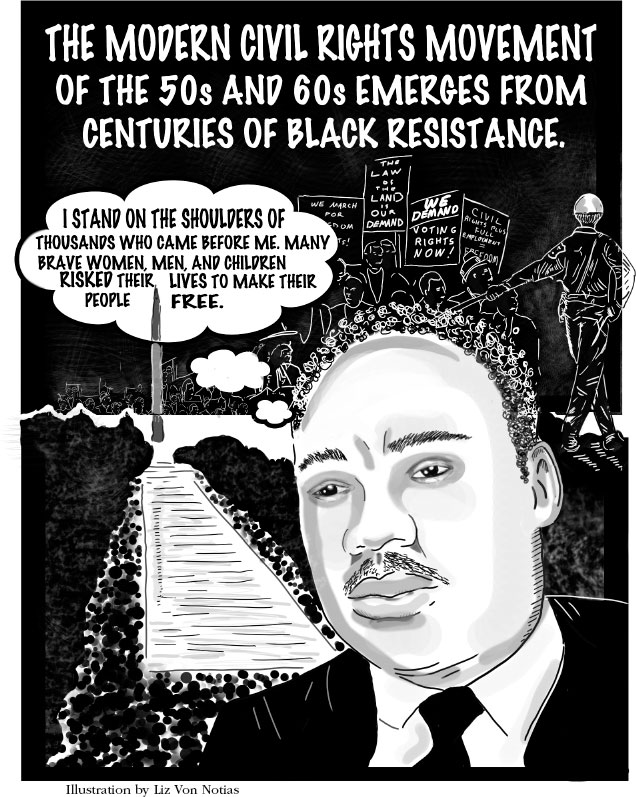

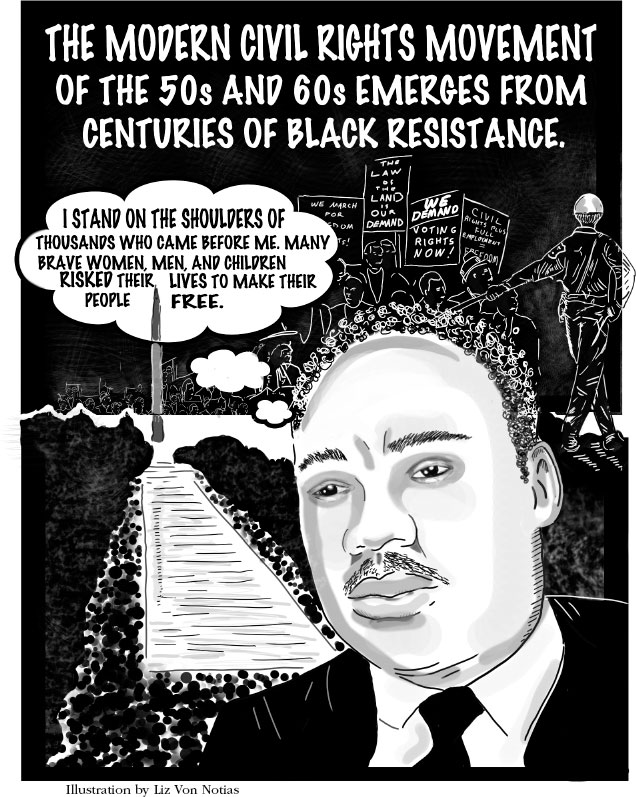

The modern civil rights movement, as this book illuminates, has its origins in resistance to slavery and white supremacy by African Americans. Blacks, by virtue of their status on the bottom of America's economic and racial rung, have always been at the cutting edge of radical movements for democracy and racial, economic, and gender justice.

Anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells innovated a style of black feminism and civil rights advocacy that made her one of the most important social justice figures of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, a Fisk University and Harvard University trained historian, sociologist, and intellectual omnivore, became the 20th century's racial justice avatar through civil rights activism that mixed prodigious scholarship with practical organizing skill that led to the founding of the NAACP in 1909.

The Great Migration of blacks from South to North and the onset of World War I in the early twentieth century helped to reshape the contours of civil rights activism. The landscape of black politics found itself reimagined by Caribbean radicals such as Hubert H. Harrison and the global ambition of the Jamaican Marcus Mosiah Garvey.

Black political activism operated, simultaneously, on several interrelated tracks. The NAACP challenged racial segregation in courts and through its literary publication, The Crisis, amassing a steady number of interracial allies in the process. Black nationalists and Pan-Africanists, personified by Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association, upheld self-determination as the key to black liberation and promptly started black businesses, political associations, and newspapers whose influence would spread across several continents. Migration transformed urban America, turning cities such as New York, St. Louis, and Chicago into cultural meccas for black artistic, musical, and literary production.

World War II provided space for black political radicals to link the black freedom struggle to the fight against fascism. The Double V campaign against the twin evils of Jim Crow and fascism drew figures such as Paul Robeson, A. Phillip Randolph, and Du Bois into robust political alliances. Scarred by the lessons of World War I, when returning black soldiers faced violence and segregation from an ungrateful nation, blacks turned the Second World War into a litmus test for the very concept of democracy and citizenship.

The March on Washington Movement, organized by Randolph and civil rights activists, successfully pushed President Franklin D. Roosevelt into signing an executive order desegregating the military and setting up fair employment practices at the federal level.

Yet despite some victories in labor activism and securing black access to New Deal programs, blacks found themselves largely shut out of postwar American prosperity. The Cold War, which attacked anti-racism as Communist propaganda, made the struggle for social justice more difficult in the 1950s.

The modern Black Power Movement emerged out of this complicated political space. While mainstream media lauded the 27-year-old Martin Luther King, Jr., who emerged as a spokesman for the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott in 1956, black New York stood enthralled by Malcolm X, the 31-year-old ex-convict and son of a Garveyite preacher.

Malcolm and Martin came for different branches of the same historical family tree. King, sensing the nation's antagonism to black equality on political grounds (even after the Supreme Court desegregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education) initially couched his pleas for justice on moral grounds. Malcolm confronted democracy's jagged edges more bluntly. He blasted white supremacy as a political ideology that had bankrupted the nation's ability to treat blacks as citizens. Malcolm identified American democracy as nothing more than hypocrisy.

The years between 1954 and 1965 represent the Civil Rights Movement's heroic period, an era in which legal and legislative victories (the Brown decision, 1964 Civil Rights Act, and 1965 Voting Rights Act); grassroots organizing (the 19551956 Montgomery Bus Boycott, 1960 sit-in movement, and 1961 Freedom Rides); massive political demonstrations (the 1963 March On Washington, the 1965 Selma-to-Montgomery demonstration); and political assassinations (Emmett Till in 1955, Medgar Evers and four black girls in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963, Schwerner, Chaney, and Goodman in 1964, and Malcolm X in 1965) combined watershed political changes with human drama that played out before a national and global audience.

But this period, and the era that followed, can rightfully be considered the time of radical black liberation in America and globally. Malcolm X helped turn the Nation of Islam (a descendant of Garvey's UNIA to which Malcolm's father Earl Little belonged) into a national organization that made inroads with black political radicals. Malcolm found inspiration in 1955's Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, and 1959's Cuban Revolution. Malcolm met with Fidel Castro in Harlem in 1960 and helped to inspire young SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee) activists and the Black Panthers.

Next page