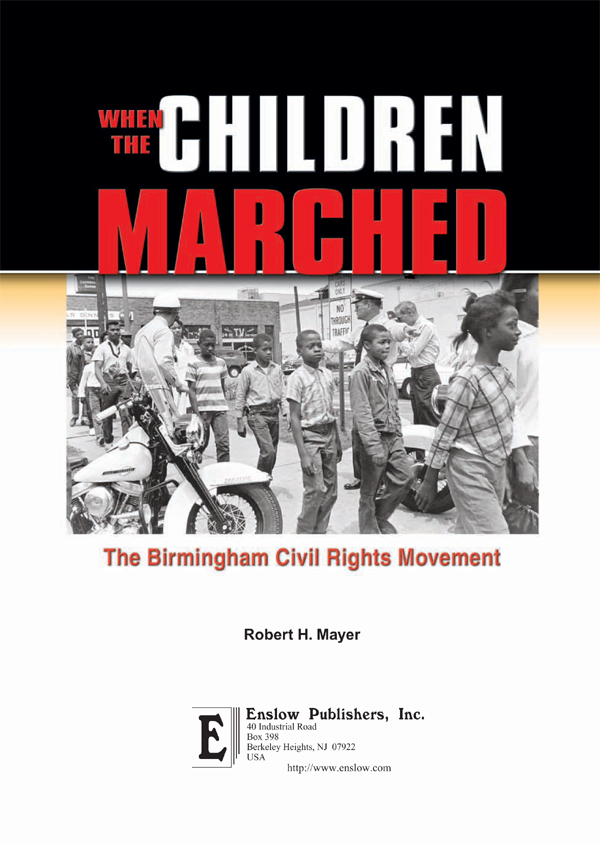

They were sprayed by fire hoses, attacked by dogs, thrown in jailand they were only kids.

Referred to as the most segregated city in America, Birmingham, Alabama, became a hotbed for civil rights activity in the early 1960s. Great African-American leaders, including Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, helped lead the civil rights movement in the city. In Birmingham, African-American youth marched, sang, and spoke out against segregation. Although they faced police dogs and fire hoses, they offered non-violent resistance and did not back down.

a well-researched, well-written, balanced account of the role young people played in the adult struggle for social justice in the Deep South.

Dr. Russell L. Adams, Professor Emeritus of Afro-American Studies at Howard University

About the Author

Robert H. Mayer is professor of education and chair of the Education Department at Moravian College. Previous to that, he served as a high school social studies teacher. Dr. Mayer is editor of The Civil Rights Act of 1964, for which he received the 2005 Carter G. Woodson Book Award.

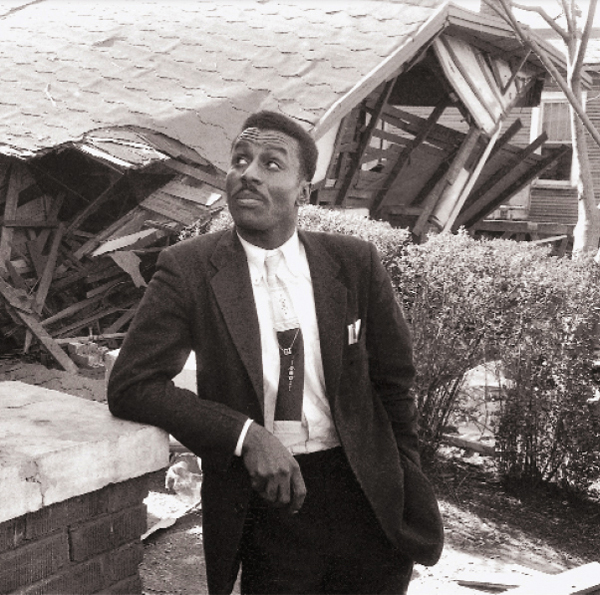

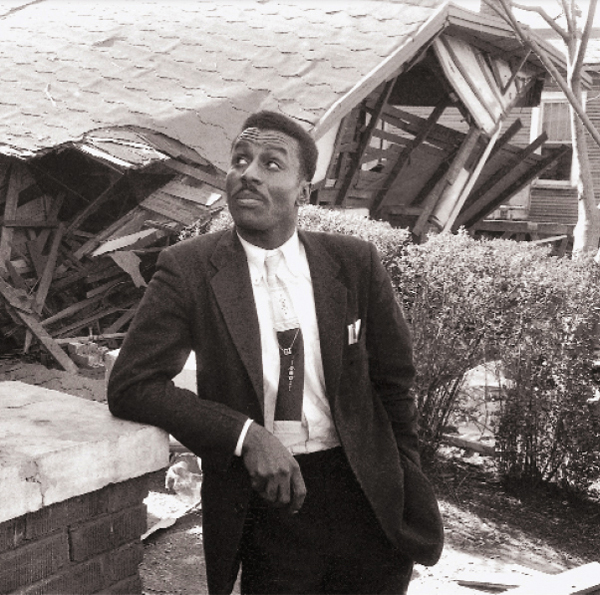

I knew in a second, [a] split second, that the only reason God saved me was to lead the fight.

The Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth

The blast echoed throughout the neighborhood. They had bombed the reverends home on Christmas night. James Roberson, a young parishioner who lived across the street, felt the shock in his own bedroom: I was home in bed. The explosion was so powerful, I thought the world was coming to an end. When Roberson gaped at the house, he saw a terrifying sight. A pillar had been torn from under the roof and the dwelling leaned to the left. Roberson feared for the people inside. From the street below he heard screaming.

Until the bomb exploded, it had been a normal, relaxing evening for the family of the Reverend Fred L. Shuttlesworth. The reverend sat in his bed talking to a visitor. His wife Ruby watched television with their daughters, Ricky and Carolyn, and a friend. Fred Junior was in the dining room admiring the new red football jersey he had gotten that morning for Christmas. He was later to recall, When I saw all that dust and stuff in the air, I knew that somebody had actually tried to kill us.

Image Credit: Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

The Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth stands outside the wreckage of his house following an assassination attempt involving sixteen sticks of dynamite in 1956.

Neighbors and church members rushed to the defense of the Shuttlesworth family. Some brought pistols; others even brought shotguns. They were enraged. But the reverend believed deeply in nonviolence. When he spoke to the crowd that night he told them, Put those guns up. Thats not what we are about. We are going to love our enemies. And Shuttlesworth had a lot of enemies.

It was Birmingham, Alabama, in 1956. Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, an African-American minister and civil rights leader, had upset many in the white community by pushing to integrate the public buses in Birmingham as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., had recently done in Montgomery, Alabama. Shuttlesworth had been threatening to bring Kings successful campaign to town. In the days after Christmas, members of the black community had planned to sit in the whites-only sections of Birmingham buses. They wanted to challenge the city laws that reserved the front seating area for whites and the back of the bus for blacks.

It was not just the buses that were segregated in the city. As one reporter who visited Birmingham said, Whites and blacks still walk the same streets. But the streets, the water supply and the sewer system are about the only public facilities they share. Ball parks and taxicabs are segregated. So are libraries.

The Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth discussed an incident that occurred right after the bombing of his home:

When I got out there was a terrific crowd all around, and one little ruddy-faced policeman was cursing out a Negro and I saw the Negro had a switchblade knife in his hand and the blade was sticking out. He had the advantage on the policeman at that time. The policeman had been rough with him, trying to make him move and everybody was mad seeing that thing that had happened. The Negro said, If you put your hand on me again, Ill cut your throat to death. You are the cause of this thing; you policemen call yourself God and are the ones who are the cause of it. You all are the Klan.

The policeman was red and I just came up and patted the young fellow [the man with the switchblade] on the back and said, What are you so mad about? I came out of this; God spared me and Im not mad at all. I want you to shut your knife up and there wont be any trouble. and the Negro shut up his knife and went on.

King called Birmingham the most segregated city in America. The Birmingham brand of Jim Crow laws, the name used for the American system of segregation that separated blacks and whites, was particularly ugly. Separate black and white facilities existed for everything including hospitals, schools, playgrounds, and cemeteries. From birth to death, life in Birmingham was segregated.

The people of Birmingham experienced segregation as a regular aspect of their daily activities. Ed Gardner, a long-time Birmingham resident and activist, described his life in this manner:

You could go downtown there in one department [of a store] and spend a thousand dollars and go to the lunch counter and be put in jail. Or you could go uptown and get on the elevator that was marked White Only, and get put in jail. And then the eating places had two doors. They had to have a sign on there, Colored and White, and then the owner had to have a wall inside there seven feet high so the black and white couldnt see each other.

Then there were the buses. James Roberson recalled a sign posted on buses that read: Colored, do not sit beyond this board. Blacks had to sit behind the sign. When more and more whites got on, blacks had to give up their seats toward the front as the sign was moved farther back.

The situation in town provoked curiosity in some. Larry Russell remembered that as a child he wondered about the taste of white water from a white drinking fountain. Was it different from colored water? One day he and a friend stayed in J. J. Newberrys, a local department store, until closing. They snuck a drink from the white fountain and discovered there was no difference between the two. He did observe the generous spray of the white fountain compared to the slow drip of the fountain he normally used. Defenders of segregation often claimed that it provided separate but equal services for blacks and whites. But in the Jim Crow South, the separate facilities for blacks and whites were never equal.

The name Jim Crow was probably first used in the 1830s when a white performer applied black cork to his face and played an insulting character he called Jim Crow. The label, soon applied to blacks in general, became one more term used throughout the country to stereotype and slur African Americans. Jim Crow went on to refer to the web of laws and customs that kept African Americans in a separated and unequal position.