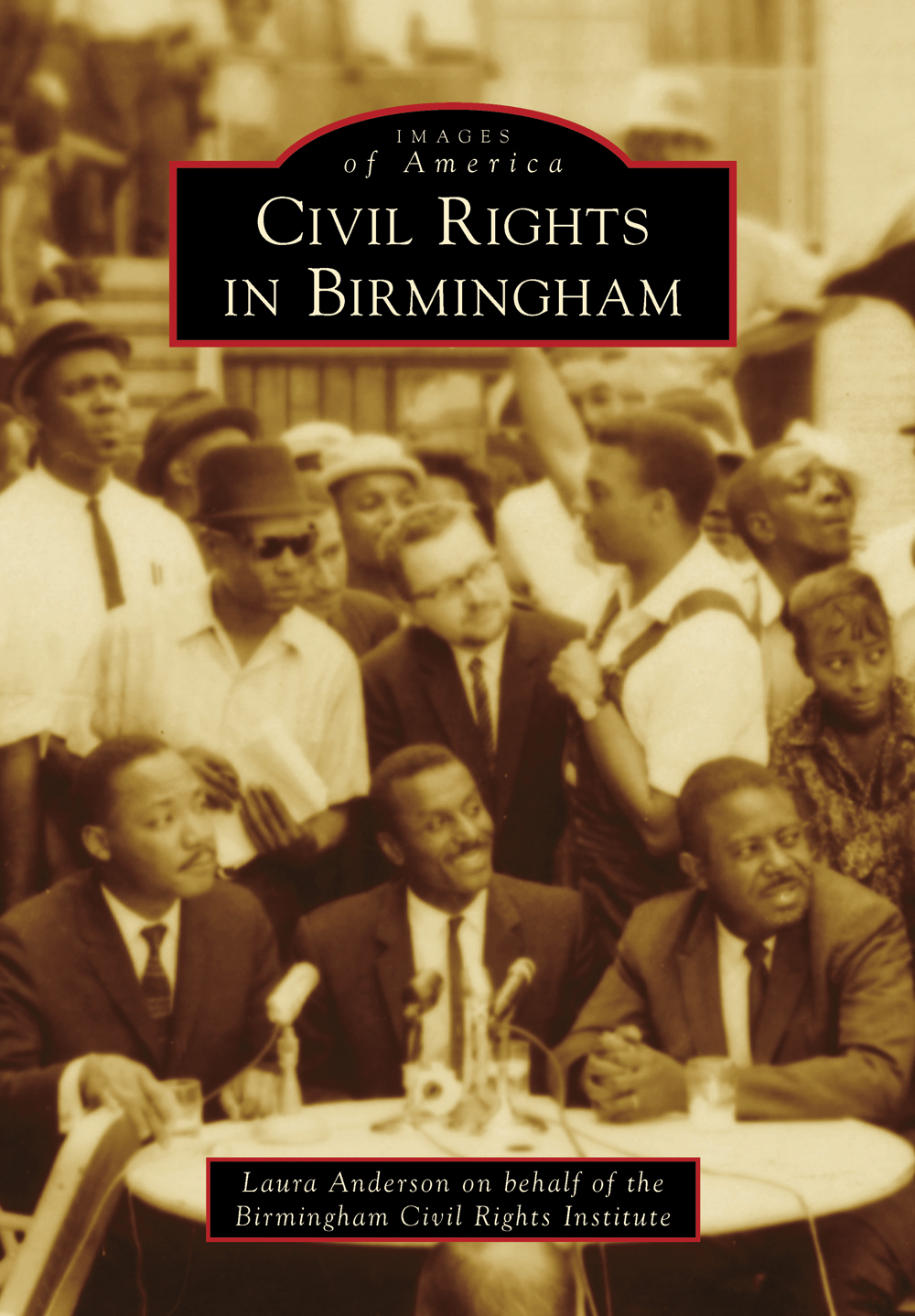

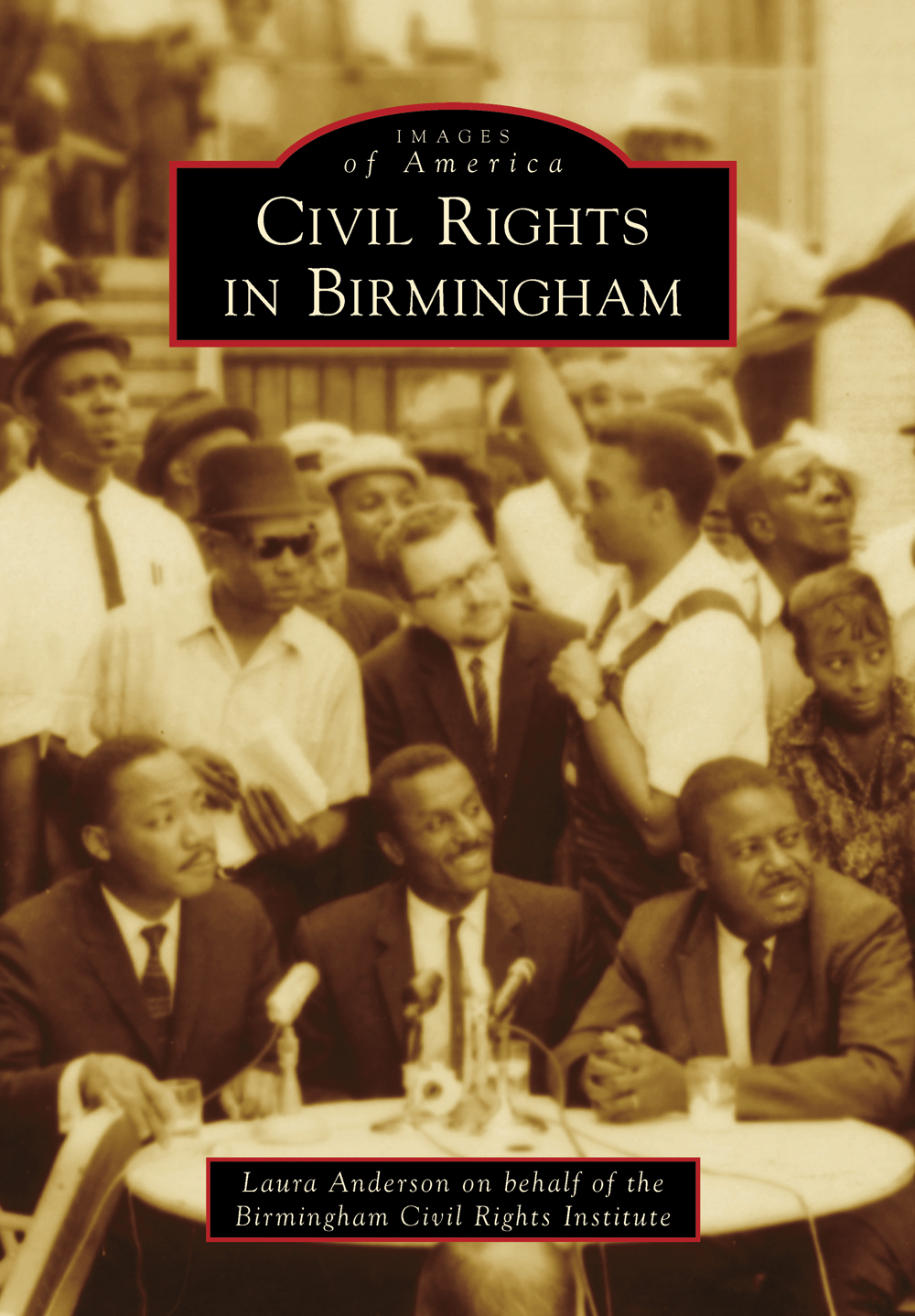

IMAGES

of America

CIVIL RIGHTS

IN BIRMINGHAM

ON THE COVER: Seated at a table in the Gaston Motel courtyard on May 10, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (left), Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth (center), and Rev. Ralph D. Abernathy publicly announce an agreement reached between the movement and white civic and business leaders of Birmingham. (Courtesy Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.)

IMAGES

of America

CIVIL RIGHTS

IN BIRMINGHAM

Laura Anderson on behalf of the

Birmingham Civil Rights Institute

Copyright 2013 by Laura Anderson on behalf of the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute

ISBN 978-1-4671-1067-9

Ebook ISBN 9781439644263

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013934881

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To countless participants in the long and ongoing movement for civil and human rights in Birmingham and around the world, especially those of whom we have no photographs.

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to my coworkers at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (BCRI), especially President and CEO Dr. Lawrence J. Pijeaux Jr., for making it such an exciting, forgiving, and high-functioning work environment. We learn every daytogetherfrom one another, from our visitors, and, above all, from the veterans of the civil rights movement, whose courage in the past inspires us daily in the fulfillment of our guiding mission: to promote civil and human rights worldwide through education. Special thanks to Ms. Odessa Woolfolk, BCRI board chair emerita and the visionary woman who cajoled donors in order that collections central to the telling of the Birmingham movement story found good homes in the BCRI Archives. Among such collections are photographs and documents from A.G. Gaston and E.O. Jackson, featured in this book.

Special thanks goes to colleagues Jim Baggett and Don Veasey at the Birmingham Public Library, Department of Archives and Manuscripts. We can always depend on their collaboration to ensure that those who seek information about, and images of, the Birmingham movement locate them. The nationally known and celebrated work of photographer Carol M. Highsmith, donated to the Library of Congress and therefore to the American people, served as a valuable resource for the final chapter of this volume. Local photographer Larry O. Gay also contributed much, which will surprise no one familiar with Larrys generosity, talent, and keen knack for always being there when events are happeningat BCRI and around the city of Birmingham.

Unless noted otherwise, images are from the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute collection. Most special words of thanks go, therefore, to donors. Many individuals, families, and grassroots organizations over the years have donated materials to the BCRI Archives. These photographs, documents, and other bits of evidence of the civil rights movement make a research experience possible for BCRI patrons and staff alike. The attempt to publish even a small book like this one underscores for us two things at once: the importance of each bit of material that we possess, and the necessity that we prevail upon more local citizens to consider what photographs or documents they may have that could find safekeeping and usefulness in the archives.

This book tells the story from photographs currently available in the BCRI Archives. We hope the photographic resources at BCRI will grow over time to more fully reflect the many individuals, grassroots organizations, churches, events, and measures of progress that characterize the ongoing movement for civil rights and human rights in our community.

INTRODUCTION

Since the citys founding in 1871, African American citizens of Birmingham, Alabama, have organized in various ways for equal access to justice, commerce, and public accommodations. However, when thousands of young people took to the streets of downtown in the spring of 1963, their protest finally broke the back of segregation, bringing local business and government leadership to its knees. While their parents could perhaps not risk loss of jobs or life, local youth agreed to bear the brunt of resistancefrom both law enforcement and vigilantesto their carefully planned acts of civil disobedience. Teenagers schooled in nonviolent tactics by staffers of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) dressed well in anticipation of going to jail. With toothbrushes in their pockets, they spilled out of the windows of their schools while teachers turned their backs at the chalkboards. They walkedin some cases several milesto Project C headquarters, at Sixteenth Street Baptist Church.

Project C (for confrontation) was the name given to the Birmingham campaign launched by multiple organizations and individuals, including the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights (ACMHR) and SCLC. Sixteenth Street Baptist Church became the setting of key mass meetings due to its relatively large size and strategic downtown location. Young demonstrators were loaded into paddy wagons and taken to jails and other detention centers, including open yards surrounded by high fencing. Some were bitten by dogs trained to attack upon command, while others were knocked over and propelled down sidewalks by the pressure of water from fire hoses. By fall, youth who did not even participate in the Childrens Movement gave all for the struggle when a bomb placed in the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church exploded and killed four girls. Before that September day was over, two boys were also murdered, victims of police brutality and tragic encounters fueled by the dehumanizing hate that characterized the learned feelings of many, though not all, whites toward blacks at that time.

Events in Birmingham, Alabama, in 1963 focused the eyes of the world on the city like never before. However, two years earlier, in the spring of 1961, CBS News aired a one-hour documentary, Who Speaks for Birmingham?, in which one young African American female resident, looking directly into the camera lens, appealed to viewers nationwide: Whether youre black, brown, red, green or yellow, dont live in Birmingham. Here, life is not worth living. During the same program, aired in prime time but not broadcast locally, leaders of the Birmingham movement made their first appearances on national television. Reverends Fred L. Shuttlesworth, C. Herbert Oliver, and Calvin Woods, among others, spoke out about encounters with law enforcement operating under the direction of Birminghams notorious commissioner, Eugene Bull Connor. His division of public safety was emblematic of a system of state-sanctioned oppression they and others vowed to defeat, or, in the words of Fred Shuttlesworth, be killed trying.

That same year, Birmingham educator Geraldine Moore published Behind the Ebony Mask, a compendium of facts, figures, and biographical profiles of persons Moore identified as prominent in the African American community and its struggle for equality. The book is the authors interpretation for a general audience of What Negroes are Doing, which was also the name of Moores column that ran in the 1950s and 1960s in Alabamas largest newspaper, the Birmingham News. Sharing her personal story of growing up in Birmingham, Moore stated in her introduction to the book, The remark has been made many times that Birmingham is one of the worst places in the world for Negroes to live. She continued, I do not hesitate to say that from the standpoint of race relations in Birmingham, some things have happened and some are still happening which I do not think are right or fair. But... since I make Birmingham my home as a result of my own choice, I do what I think is the only logical thing to dotry to make the most of my opportunities, however limited they may be.

Next page