Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Nora

The vote is the most powerful instrument ever devised by man for breaking down injustice.

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON,

AUGUST 6, 1965

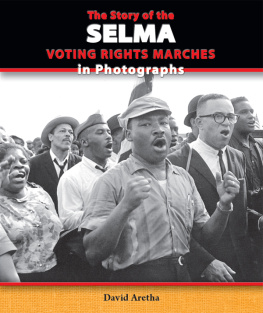

Fifty years after he nearly died in the most important march in American civil rights history, Congressman John Lewis returned to Selma, Alabama, on March 7, 2015.

Hail to the Chief played as Lewis followed President Barack Obama and former president George W. Bush across Water Avenue in downtown Selma to a podium at the foot of the Edmund Pettus Bridge, named after a former Grand Dragon of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan. One hundred members of Congress, who accompanied Lewis on this civil rights pilgrimage, sat nearby on the blindingly sunny afternoon. A few Democratic senators, including Elizabeth Warren from Massachusetts, held signs that read, VOTING RIGHTS ARE CIVIL RIGHTS .

Luci Baines Johnson, the daughter of the former president Lyndon Johnson, sat a few feet away from Peggy Wallace Kennedy, the daughter of the former Alabama governor George Wallace. Their fathers had fought on opposite sides of the battle for civil rights.

Behind the dignitaries, sixty thousand people, some from as far away as South Africa, had converged on Selma to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the Bloody Sunday march. It was the largest crowd the small city of twenty thousand had ever seen.

This city, on the banks of the Alabama River, gave birth to a movement that changed America forever, Lewis said. Our country will never, ever be the same because of what happened on this bridge. He looked at President Obama. If someone had told me, when we were crossing this bridge, that one day I would be back here introducing the first African-American president, I would have said you were crazy. The president rose and tightly embraced Lewis. He called the seventy-five-year-old congressman from Georgia one of my heroes. Then he paid tribute to the Selma marchers.

There are places and moments in America where this nations destiny has been decided, the president said. Selma is such a place. In one afternoon fifty years ago, so much of our turbulent historythe stain of slavery and anguish of civil war, the yoke of segregation and tyranny of Jim Crow, the death of four little girls in Birmingham, and the dream of a Baptist preacherall that history met on this bridge.

After his speech, the president walked across the Edmund Pettus Bridge hand in hand with Lewis and Amelia Boynton, a one-hundred-three-year-old voting rights activist from Selma who had been beaten unconscious fifty years earlier. The children of Martin Luther King, Jr., marched behind them. The group sang, Woke up this morning with my mind / Stayed on freedom, as they climbed the bridge. At the top, high above the Alabama River, Lewis grabbed a bullhorn and retold the story of Bloody Sunday.

* * *

In 1965, Lewis had walked this same route under far more treacherous conditions. King had called for a march from Selma to Montgomery, the state capital, to protest the death of twenty-six-year-old Jimmie Lee Jackson, who was shot by the police while trying to protect his mother after Alabama state troopers attacked a nighttime civil rights demonstration in Marion, Alabama. Jackson made six dollars a day as a woodcutter and was the youngest deacon in his church. Hed tried unsuccessfully to register to vote five times in Perry County, where only 265 of 5,202 eligible black voters were on the voting rolls. Jimmie Jackson just wanted to vote, King said at his funeral. Now we must see that Jimmie Jackson didnt die in vain.

Perry County adjoins Selma, the central front in the civil rights movements campaign to win the right to vote across the segregated South. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had been trying to register voters there since 1963. It hadnt gotten very far. When SNCC arrived in Selma, only 156 of the countys 15,000 eligible black citizens were registered to vote. After two years of work, that number had inched up to a mere 335.

On the afternoon of March 7, 1965, Lewis, the twenty-five-year-old chairman of SNCC, threw an orange, an apple, a toothbrush, toothpaste, and two books (Richard Hofstadters The American Political Tradition and the Men Who Made It and New Seeds of Contemplation , by the theologian Thomas Merton) into his green army backpack and headed over to Brown Chapel, the redbrick headquarters of Selmas civil rights movement. Were marching today to dramatize to the nation and to the world, he told reporters outside the church, that hundreds and thousands of Negro citizens of Alabama, particularly here in the Black Belt area, are denied the right to vote.

Lewis and six hundred marchers came face-to-face with an army of blue-helmeted Alabama state troopers when they reached the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Maj. John Cloud told them to advance no farther. He said they had two minutes to return to their church. Lewis and the others knelt to pray. After one minute and five seconds, the officers put on their gas masks, and, charging into the crowd, brutally clubbed the marchers. Lewis was hit first. When he curled up in the prayer for protection position, raising his left hand to shield himself, Lewis was clubbed again by the same state trooper across the left side of his head. He blacked out. I lost all consciousness, he later said. I saw death. I really thought I was going to die. I thought it was the last protest.

That evening ABC interrupted its prime-time premiere of Judgment at Nuremberg to show fifteen minutes of the horrific footage from Selma to forty-eight million Americans. Many confused viewers thought they were seeing images of Nazi Germany. There had been ample public outrage over atrocities committed against the civil rights movementwhen four young girls were killed by a bombing at the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham in 1963 or when three young men were murdered by the Klan in Mississippi during Freedom Summer in 1964but nothing before had the impact of Bloody Sunday.

Eight days later President Johnson introduced the Voting Rights Act (VRA) before a joint session of Congress. It is wrongdeadly wrongto deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country, the president said in his slow Texan drawl.

One hundred years after the end of the Civil War, the VRA guaranteed the franchise for black Americans and other minority groups and fulfilled the long-overdue promise of the Fifteenth Amendment of 1870, which states that the right to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude. The VRA quickly became known as the most important piece of civil rights legislation in the twentieth century and one of the most transformational laws ever passed by Congress.

It suspended literacy tests across the South, authorized the U.S. attorney general to file lawsuits challenging the poll tax, replaced recalcitrant registrars with federal examiners, dispatched federal observers to monitor elections, forced states with the worst histories of voting discrimination to clear electoral changes with the federal government to prevent future discrimination, and laid the foundation for generations of minority elected officials.