By the same author

The Office of Management and Budget and the Presidency, 19211979

You are now getting some unjust criticism, but remember that the most criticized men in American history were those whose names shone brightest in historysuch as Lincoln, Wilson and Roosevelt. Also, remember they crucified Jesus within three years after He began His ministry. It is what God thinks about our actionsand what history will say a hundred years from nowthat really counts. Therefore, it is my prayer now that you will continue to face the somber realities of this hour with faith and courage. The Communists are moving fast toward their goal of world revolution. Perhaps God brought you to the Kingdom for such an hour as thisto stop them. In doing so, you could be the man that helped save Christian civilization.

Personal letter from the Rev. Billy Graham to President Johnson, July 11, 1965 (emphasis added)

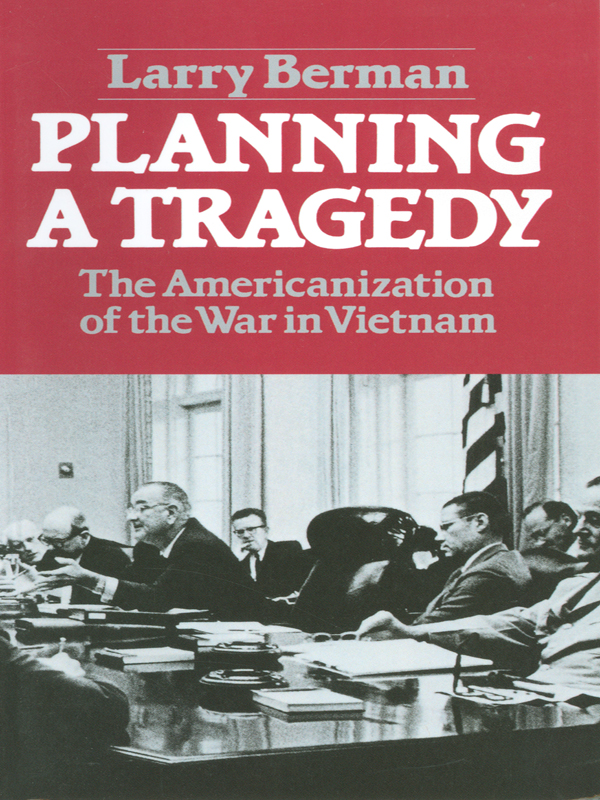

Planning a Tragedy

The Americanization of the War in Vietnam

LARRY BERMAN

W W NORTON & COMPANY NEW YORK LONDON

First Edition

Copyright 1982 by Larry Berman

All rights reserved.

Published simultaneously in Canada by George J. McLeod Limited, Toronto.

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Berman, Larry.

Planning a tragedy.

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Vietnamese Conflict, 19611975United States.

2. United StatesPolitics and government19631969.

3. Political scienceDecision making. I. Title.

DS558.B47 1982 950.7043 8122570 AACR2

ISBN 13: 978-0-393-95326-8

ISBN 13: 978-0-393-24257-7 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

W. W. Norton & Company, Ltd. 37 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3NU

For my mother and the memory of my father

Contents

President Johnson preferred to describe the period as the most productive and most historic legislative week in Washington during this century,1 but it will be remembered as the week Lyndon Johnson led America into war on the Asian mainland. The lead stories of late July 1965 in the New York Times and Washington Post focused neither on the final stages of Medicare nor on the historic Voting Rights Bill, but rather on the Vietnam policy review then underway within the White House. A war climate permeated the nations capital, fueled by such foreboding headlines as Johnson Probes Vietnam Crisis with Top AidesParley Viewed as Prelude to Troop Buildup and U.S. Moves Closer to Policy Decision on VietnamPresident Holds Talks With Joint Chiefs of Staff and Foreign Relations AidesReserves Are StudiedCommitting of Up to 200,000 Men Weighed in a Mood of Secrecy and Urgency.2

By July 1965 the political and military conditions within South Vietnam were in a state of such turmoil that the policy options confronting President Johnson were infinitely more complex than those which had faced his predecessors. No longer would increments in financial aid, verbal support, or military personnel be sufficient to constitute U.S. policy. No, the fundamental fact of international politics in July 1965 was South Vietnams impending fall to Communist control, unless the United States provided enough ground support to deny Hanoi its goal of unifying Vietnam under Communist leadership. Lyndon Johnsons time of reckoning had arrivedwould he bite the bullet and, in his favorite phrase, turn in his stack to meet the needs of a fledgling and free South Vietnam or would he lead a systematic reappraisal of U.S. interests and objectives which concluded that no matter how much the ante was raised, the United States could not achieve its goal of containing communism in the jungles of Vietnam? Moreover, could Lyndon Johnson have then led the country away from war in the summer of 1965?

On July 28 President Johnson announced that U.S. fighting strength in Vietnam would immediately be increased from 75,000 to 125,000 and that additional U.S. forces would be sent as they were requested by field commander Gen. William Westmoreland.3 This military obligation, taken in response to the rapidly deteriorating political and military situation in South Vietnam, would be achieved through substantial increases in monthly draft calls but, contrary to all previous indications from the White House, no Reserve or National Guard units would be called into service.

The presidents decision resulted from extensive deliberations among foreign policy advisors and between these advisors and the president. In his backgrounding of the press, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara emphasized that not since the Cuban missile crisis had such care been taken in making a decision. On the average of four hours per day has been spent with the President in discussing the problem. In addition, the President sought the advice of every responsible government official in coming to a decision.4 These White House deliberations reflected what is generally assumed to be one of the few times that the principal Vietnam advisors focused intensively on fundamental questions of policy and not solely on the technicalities of military strategy. For approximately one month the president and his chief foreign policy advisors faced crucial questions concerning Americas global objectives, vital interests, policy options, and their probable effects. All of those involved understood that to proceed as indicated above would mean a lengthy American military commitment to a land war in Vietnam.

The case selection was based on the significance of a decision which fully committed the United States to a land war in Vietnam as well as the availability of recently declassified primary source documents from the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library. These materials provide a detailed, dramatic, and often compelling perspective of how advisors worked in what can only be described as a decisionmaking microcosm. The documents graphically depict the human element, perhaps a human tragedy, of president and advisors searching for a way out of sending American troops to fight and die on the Asian mainland, yet each unwilling to accept the consequences of such logic. Readers of earlier drafts urged me to tell the story by letting the documents speak. This historical record illustrates how events can often shape the parameters of decision choice; how situations can deny flexibility in response; how individual world view influences the definition of a situation; how official institutional rank can place advisors in quite unequal advocacy positions; how advisor role definitions can influence advocacy strategy; and most important, how no one decision can be studied in isolation from what preceded it.

A descriptive narrative of the decision process constitutes the core of the text. I have no grand theory for explaining the failure of Vietnam decision-making, nor do I believe that one is necessary. One of the lost arts in the discipline of political science is analyzing the impact of political institutions, processes, and personalities during critical turning points in history. The Vietnam War was, at once, a human and a national tragedy. Yet the complete record of that episode is just now being made available through declassification of White House records. The background chronology in Chapter Two relies on previously published and secondary sources. In Chapters Three and Four I have tried to capture the dynamics of decision choice by utilizing the hitherto unavailable materials. From the complete written record I then draw conclusions for how and why such a tragic decision was made.

Retrospective evaluation of the Vietnam War should be approached with great care. The foreign policy failed, driving a president and the architects of that policy from office. I have tried always to recall McGeorge Bundys personal advice that the trick to bringing documents into history is not to neglect the rest of history. But the reader should know that this history is viewed primarily as a projection of how decision-makers themselves viewed the world and American politics in 1965. Wherever possible I have supplemented the written record with personal interviews and oral history transcripts. Manuscript drafts were circulated to each of the principal decision-makers identified in the text. I have also benefited from the recent declassification of the BDM Corporation study The Strategic Lessons Learned in Vietnam.5

Next page