Contents

Guide

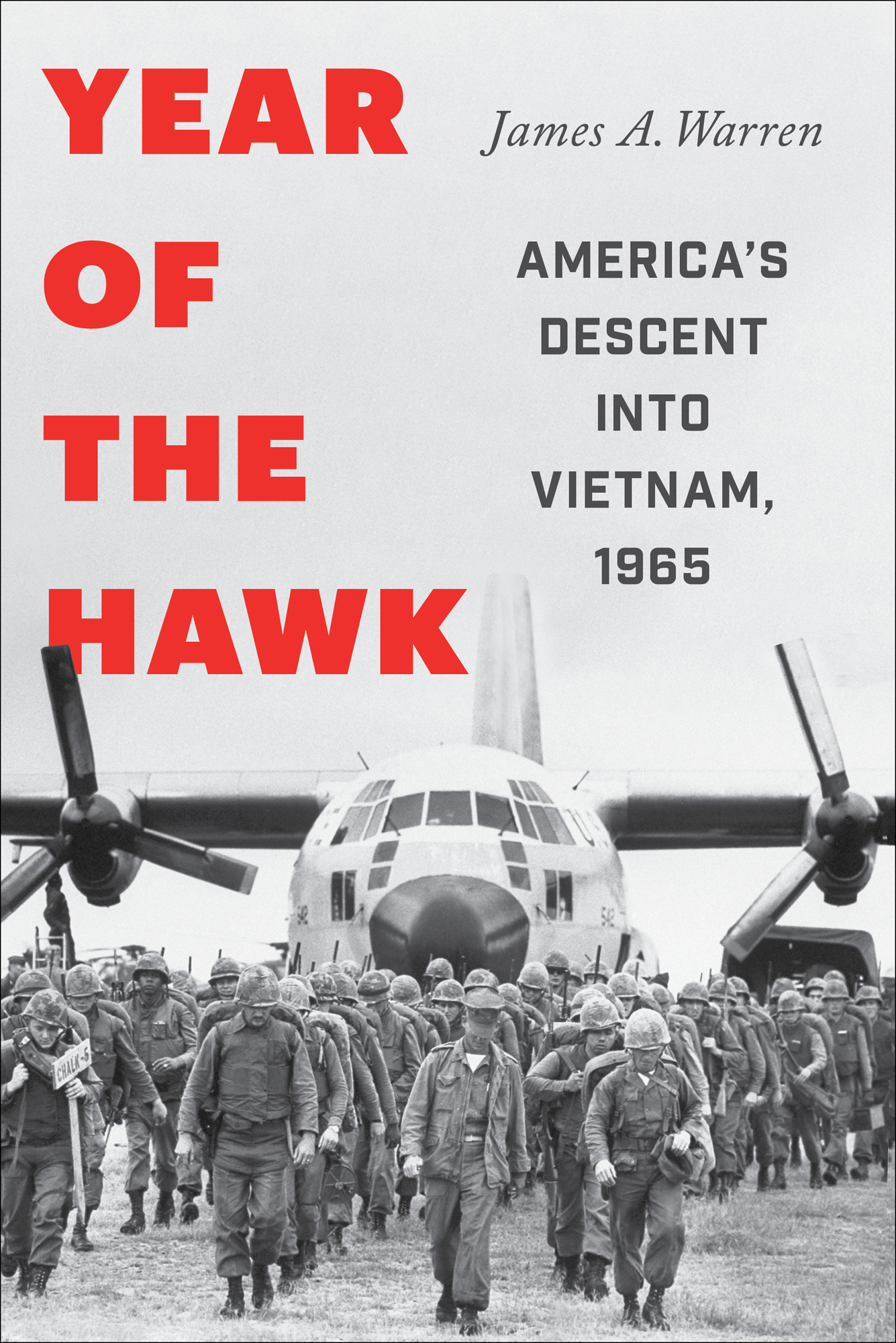

Year Of The Hawk

James A. Warren

Americas Descent into Vietnam, 1965

ALSO BY JAMES A. WARREN

God, War, and Providence: The Epic Struggle of Roger Williams and the Narragansett Indians Against the Puritans of New England

Giap: The General Who Defeated America in Vietnam

American Spartans: The U.S. Marines: A Combat History from Iwo Jima to Iraq

The Lions of Iwo Jima: The Story of Combat Team 28 and the Bloodiest Battle in Marine Corps History, coauthored with Major General Fred Haynes (USMC-RET)

Scribner

An Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

1230 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

www.SimonandSchuster.com

Copyright 2021 by James A. Warren

All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever. For information, address Scribner Subsidiary Rights Department, 1230 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10020.

First Scribner hardcover edition November 2021

SCRIBNER and design are registered trademarks of The Gale Group, Inc., used under license by Simon & Schuster, Inc., the publisher of this work.

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact Simon & Schuster Special Sales at 1-866-506-1949 or .

The Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau can bring authors to your live event. For more information or to book an event, contact the Simon & Schuster Speakers Bureau at 1-866-248-3049 or visit our website at www.simonspeakers.com.

Interior design by Wendy Blum

Jacket Design by Jason Arias

Jacket Photograph by Larry Burrows/Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

ISBN 978-1-9821-2294-2

ISBN 978-1-9821-2296-6 (ebook)

This book is for all the Americans and Vietnamese who fought in the Vietnam War.

INTRODUCTION: AMERICA IN 1965

In 1965, the United States of America was widely regarded as the most powerful and prosperous nation on earth. As the undisputed leader of the Free World, the country was in the forefront of expanding the boundaries of democracy and liberty abroad. Its military power was the major bulwark against communist expansionism in Europe and Asia. The US economy, along with Americans increasingly consumer-driven way of life, was the envy of much of the rest of the world. Indeed, the American economy that year set new records in terms of gross national product, total sales of goods, numbers of people employed, and total income. The inflation rate rose slightly to a very manageable 1.59 percent. A loaf of bread cost twenty-one cents, gasoline was thirty cents a gallon, and the average home cost $13,500only a bit more than twice the average yearly income of $6,400.

Millions of the nations World War II veterans and their families had already escaped the congested cities for the crabgrass frontier, the suburbs, where they lived lives of material abundance that would have astonished their parents. Millions more Americans planned to do the same, and soon. High school graduates in America were flooding into four-year colleges in unprecedented numbers, and a rising percentage of those students were women.

In 1965, there were 194 million Americans. The big movies of the year were The Sound of Music, a heartwarming story about a real-life childrens singing group and their governess in Austria just before World War II, and Thunderball, a spy movie about stolen atomic bombs starring Sean Connery as the suave British secret agent James Bond. Teenagers in America were nuts about two new arrivals on department store shelves: Super Balls and skateboards. Young men were beginning to wear their hair longer than their parents liked. The latest womens fashion craze was the miniskirt, a welcome development in the eyes of straight young men.

The American people, its fair to say, were by and large an optimistic and confident bunch. Their republic had been tested in the annealing fires of a civil war, two world wars, a devastating depression, and most recently by the assassination of a beloved president and war hero, John F. Kennedy. The country, in short, seemed by almost any measure to be at the forefront of history. There were challenges ahead, to be sure, but the future looked bright.

That wise and judicious Puritan, Governor John Winthrop of Massachusetts, where John Kennedy had grown up, had spoken of America as early as 1630 as a city upon a hill, a beacon of hope and light to the troubled souls of the Old World. The idea that America was somehow different, closer to Gods vision of what a human society should look like than any other nation, still held firm. The notion that America was special in the eyes of God, and the eyes of ordinary human beings as well, undergirded the efforts of President Lyndon Baines Johnsons ambitious program of legislation called the Great Society. The purpose of the program, to put it simply, was to close the gap between American ideals and the realities of American life as it was lived among the poor and disadvantaged by granting them access to better housing, jobs, health care, and schooling.

Yet beneath all the optimism and the prosperity, there were unmistakable signs of racial and social turbulence, and revolutionary change. The most important and obvious struggle grew out of Black Americans concerted effort to obtain voting rights, equal justice under law, and access to the American dream. The effort to strip away the legal basis of segregation in the South, and integrate Blacks into a largely white society was enthusiastically embraced by an increasingly influential bastion of liberal democratic reformersclergy, academics, students, and politicians. But millions of ordinary Americansin the North as well as the Southsaw such radical change as a threat to their own notions of propriety and good social order. They resisted change, often strenuously. Violence, often shockingly brutal violence inflicted by police as well as civilians against nonviolent protesters, was increasingly common at civil rights demonstrations. The understandable rage of the Black community in the face of this resistance manifested itself in many ways. The Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. continued to preach nonviolence to his legions of followers. Not everyone was so patient. In August, in the Black section of Los Angeles, Watts, violence and chaos reigned for five days of riots. After it was all over, thirty-four people had been killed and $40 million worth of property destroyed.

Amid all this racial tension, there were subtle signs of an emerging counterculture on college campuses and in urban areas, where mostly white, middle-class students were drawn to the work of antiestablishment writers like the beat poets and novelists Ken Kesey and Jack Kerouac. These artists expressed an interest in Eastern mysticism, spiritual spontaneity, and unconventional lifestyles. Young people were drawn as well to rock and roll musicians like Elvis Presley, the Beatles, and the Rolling Stones, and to experimenting with pot and other drugs. These young Americans were increasingly critical of the complacency and materialism of mainstream consumer culture. They wanted something different, something better, something more fulfilling, though they were not yet sure exactly what it was.