ALTHOUGH WRITING HISTORY IS A SOLITARY ACT, I HAVE, TO PARAPHRASE Tennessee Williams, relied greatly on the kindness of strangers. First there are the many writers whose books and articles on the struggle for black equality inspired me and informed this work. They are, in alphabetical order, Taylor Branch, Charles Fager, Adam Fairclough, Frye Gaillard, David J. Garrow, Steven F. Lawson, Stephen Oates, Harvard Sitkoff, J. Mills Thornton, III, and, especially, Professor Richard M. Valelly of Swarthmore College, who generously took time from his busy schedule to review chapter 8 and alerted me to inadvertent factual errors. Any that remain are solely my own.

There are also several journalists who covered the events depicted in this book, giving me what Alan Barth called the first rough draft of history: Renata Adler, Alvin Benn, the late Marshall Frady, John Herbers, the late Jack Nelson, Roy Reed, and Frank Sikora. I would especially like to thank John Fleming of the Anniston Star, who loaned me the FBI records on the murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson that he collected while researching this case. They enabled me to write with more authority about that tragedy. Thanks, too, to Frye Gaillard, who allowed me to examine the interviews he conducted while writing Cradle of Freedom, and Professor John H. Roper, who shared his interviews with Congressman Don Edwards with me.

The historians unsung heroes are the many archivists whose labors provide us with the records that are essential to our work. Those who helped me are John F. Fox Jr., the FBIs resident historian; Maureen Hill at the Atlanta branch of the National Archives; Allen Fisher and Regina Greenwald at the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library; John Fletcher and Jonathan Roscoe at the Richard Nixon Presidential Library; and Tim Holtz at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library.

John W. Wright, my agent, brought me together again with Lara Heimert, who edited my third book while she was at Yale University Press and is now the publisher at Basic Books. Lara and her brilliant staff turned a long, unwieldy manuscript into a better book. Special thanks go to my editor, Alex Littlefield, whose hard work is evident on every page; the wonderful Melissa Veronesi, the books project editor, who oversaw its progress through the various stages of production; Josephine Mariea, a brilliant copy editor; the gifted Nicole Caputo and Andrea Cardenas, who are responsible for the evocative cover design; and Editorial Assistant Katy ODonnell, the Jacqueline of all trades.

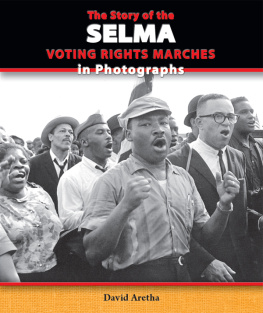

George Watson, dean of the University of Delawares College of Arts and Sciences, granted me sabbatical time that enabled me to complete this work. Associate Dean Ann Ardis was especially kind during a difficult period, and the department of historys Faculty Support Fund helped me acquire the photographs that illustrate the chapters. Others who helped me obtain photos were Elizabeth Partridge, author of Marching for Freedom, who recommended several excellent sources; Casey Anderson and Dana Caragiulo of Corbis; Tracy Martin, daughter and custodian of Spider Martins superb collection; Matt Herron, a distinguished recorder of many of these events, and Lorraine Goonan of the Image Works, who made Mr. Herrons photos available to me; Michael Schulman of Magnum Photos; the LBJ Librarys Christopher Banks; and Nancy Mirshah at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library.

Those closest to me are always the hardest to thank and deserve it the most. My daughter, Joanna, and son, Jeff, have been constant sources of pride and encouragement. And then there is Gail, who has shared my life for forty years and claims not to have regretted a single moment. I like to believe thats true, but I regret the too-many times she spent alone while I was writing; I marvel at how she managed to maintain her optimism when mine flagged. Thats why this book belongs to her. Finally, although theyll never know it, two others have greatly enriched my life: Darcy, who left me in 2011, and Izzy, who arrived four months later to take her place. Only dog lovers will appreciate why these sentences, maudlin though they may be, are true.

GM

Newark, Delaware

September 29, 2012

BY 1962 THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT HAD ALL BUT GIVEN UP ON SELMA, Alabama. Bernard Lafayette, a twenty-one-year-old member of the recently created Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), learned as much that summer when he visited the organizations headquarters in Atlanta. A city of some thirty thousand people, 57 percent of whom were black residents, Selma was the seat of Dallas County, an area encompassing roughly a thousand square miles in central Alabama. The racial inequality of this area was legendary; it was so entrenched and institutionalized that SNCC had practically no luck in its attempts to organize the citys black population so as to fight for their civil rights. The economic plight of blacks was even more serious: more than two-thirds lived below the poverty line, barely subsisting on what they earned by working the land as sharecroppers and farm hands or as the citys laborers, janitors, and maids. For SNCC Selma seemed like a hopeless case. But for Lafayette it represented a golden opportunity.

A student at Nashvilles Fisk University, Lafayette had just finished his final exams and longed to return to his more exciting life as a committed civil rights activist. He was a veteran of Nashvilles sit-in movement and had spent the last several years honing his skills as a nonviolent protestor in some of the civil rights movements most dangerous battlegrounds. Now, in the summer of 1962, he was again looking for a project he could call his ownand he was

Born in Tampa, Florida, and reared in the local chapter of the Baptist Church that his grandmother founded, Lafayettes ancestry was an unusual mix of African, Cuban, Bahamian, and French. Sophisticated and smart, he was naturally drawn to religion, and after receiving his ministers license in 1958, he sought further instruction at Nashvilles American Baptist Theological (ABT) Seminary, where he roomed with John Lewis, a shy, earnest young man from Alabama. Both were attracted first to the Reverend Kelly Miller Smith who, in 1957, joined Martin Luther King Jr. in organizing the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and later became head of its Nashville branch. Fusing Christianity with social activism, Smith risked his six-year-old daughters life in the violent struggle to integrate the citys schools. For Lafayette and Lewis, the hefty, handsome preacher was a model of inspiration and emulation.

It was Smith who introduced Lafayette and Lewis to an even more influential figure, Reverend James Lawson Jr. Born into a family of Ohio Methodist ministers, Lawson received his own preachers license when he graduated from high school in 1957. But he followed his faith in a different direction. Joining the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), he became a committed Christian pacifist. It cost him his freedom when he was imprisoned for thirteen months in 1951 for refusing to fight in the Korean War. His interest in Gandhis principles took him to the city of Nagpur in central India, where he was a teacher and campus minister at Hislop College from 1952 to 1955. He came to Nashville in 1957, studying at Vanderbilts Divinity School and holding Tuesday night workshops, at which he taught his brand of nonviolent civil disobedience that was rooted in Christianity.

Lafayette and Lewis attended Lawsons Nashville workshops and were struck by the spiritual power of his appeal for nonviolence. When you are a child of God... you try thereby to imitate Jesus, in the midst of evil, Lawson told his students. If someone slaps you on the one cheek, you turn the other cheek, which is an act of resistance. It means that you... recognize that even the enemy has a spark of God in them... and therefore needs to be treated as you, yourself, want to be treated. Lafayette and Lewisalong with figures like James Bevel, Diane Nash, and C. T. Vivianlater became prominent