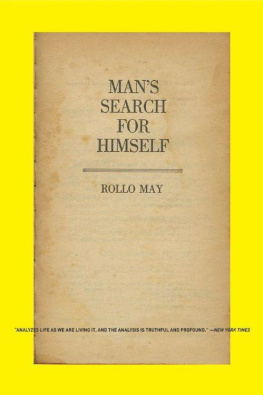

MANS SEARCH

FOR HIMSELF

Rollo May, Ph.D.

To venture causes anxiety, but not to venture is to lose ones self.... And to venture in the highest sense is precisely to become conscious of ones self.

Kierkegaard

The one goeth to his neighbor because he seeketh himself, and the other because he would fain lose himself. Your bad love to yourselves maketh solitude a prison to you.

Nietzsche

Contents

O NE of the few blessings of living in an age of anxiety is that we are forced to become aware of ourselves. When our society, in its time of upheaval in standards and values, can give us no clear picture of what we are and what we ought to be, as Matthew Arnold puts it, we are thrown back on the search for ourselves. The painful insecurity on all sides gives us new incentive to ask, Is there perhaps some important source of guidance and strength we have overlooked?

I realize, of course, that this is not generally called a blessing. People ask, rather, How can anyone attain inner integration in such a disintegrated world? Or they question, How can anyone undertake the long development toward self-realization in a time when practically nothing is certain, either in the present or the future?

Most thoughtful people have pondered these questions. The psychotherapist has no magic answers. To be sure, the new light which depth-psychology throws on the buried motives which make us think and feel and act the way we do should be of crucial help in ones search for ones self. But there is something in addition to his technical training and his own self-understanding which gives an author the courage to rush in where angels fear to tread and offer his ideas and experience on the difficult questions which we shall confront in this book.

This something is the wisdom the psychotherapist gains in working with people who are striving to overcome their problems. He has the extraordinary, if often taxing, privilege of accompanying persons through their intimate and profound struggles to gain new integration. And dull indeed would be the therapist who did not get glimpses into what blinds people in our day from themselves, and what blocks them in finding values and goals they can affirm.

Alfred Adler once said, referring to the childrens school he had founded in Vienna, The pupils teach the teachers. It is always thus in psychotherapy. And I do not see how the therapist can be anything but deeply grateful for what he is daily taught about the issues and dignity of life by those who are called his patients.

I am also grateful to my colleagues for the many things I have learned from them on these points; and to the students and faculty of Mills College in California for their rich and stimulating reactions when I discussed some of these ideas with them in my Centennial lectures there on Personal Integrity in an Age of Anxiety.

This book is not a substitute for psychotherapy. Nor is it a self-help book in the sense that it promises cheap and easy cures overnight. But in another worthy and profound sense every good book is a self-help bookit helps the reader, through seeing himself and his own experiences reflected in the book, to gain new light on his own problems of personal integration. I hope this is that kind of book.

In these chapters we shall look not only to the new insights of psychology on the hidden levels of the self, but also to the wisdom of those who through the ages, in the fields of literature, philosophy, and ethics, have sought to understand how man can best meet his insecurity and personal crises, and turn them to constructive uses. Our aim is to discover ways in which we can stand against the insecurity of our time, to find a center of strength within ourselves, and as far as we can, to point the way toward achieving values and goals which can be depended upon in a day when very little is secure.

R OLLO M AY

N EW Y ORK C ITY

W HAT are the major, inner problems of people in our day? When we look beneath the outward occasions for peoples disturbances, such as the threat of war, the draft, and economic uncertainty, what do we find are the underlying conflicts? To be sure, the symptoms of disturbance which people describe, in our age as in any other, are unhappiness, inability to decide about marriage or vocations, general despair and meaninglessness in their lives, and so on. But what underlies these symptoms?

At the beginning of the twentieth century, the most common cause of such problems was what Sigmund Freud so well describedthe persons difficulty in accepting the instinctual, sexual side of life and the resulting conflict between sexual impulses and social taboos. Then in the 1920s Otto Rank wrote that the underlying roots of peoples psychological problems at that time were feelings of inferiority, inadequacy and guilt. In the 1930s the focus of psychological conflict shifted again: the common denominator then, as Karen Horney pointed out, was hostility between individuals and groups, often connected with the competitive feelings of who gets ahead of whom. What are the root problems in our middle of the twentieth century?

It may sound surprising when I say, on the basis of my own clinical practice as well as that of my psychological and psychiatric colleagues, that the chief problem of people in the middle decade of the twentieth century is emptiness . By that I mean not only that many people do not know what they want; they often do not have any clear idea of what they feel. When they talk about lack of autonomy, or lament their inability to make decisionsdifficulties which are present in all decadesit soon becomes evident that their underlying problem is that they have no definite experience of their own desires or wants. Thus they feel swayed this way and that, with painful feelings of powerlessness, because they feel vacuous, empty. The complaint which leads them to come for help may be, for example, that their love relationships always break up or that they cannot go through with marriage plans or are dissatisfied with the marriage partner. But they do not talk long before they make it clear that they expect the marriage partner, real or hoped-for, to fill some lack, some vacancy within themselves; and they are anxious and angry because he or she doesnt.

They generally can talk fluently about what they should wantto complete their college degrees successfully, to get a job, to fall in love and marry and raise a familybut it is soon evident, even to them, that they are describing what others, parents, professors, employers, expect of them rather than what they themselves want. Two decades ago such external goals could be taken seriously; but now the person realizes, even as he talks, that actually his parents and society do not make all these requirements of him. In theory at least, his parents have told him time and again that they give him freedom to make decisions for himself. And furthermore the person realizes himself that it will not help him to pursue such external goals. But that only makes his problem the more difficult, since he has so little conviction or sense of the reality of his own goals. As one person put it, Im just a collection of mirrors, reflecting what everyone else expects of me.

Next page