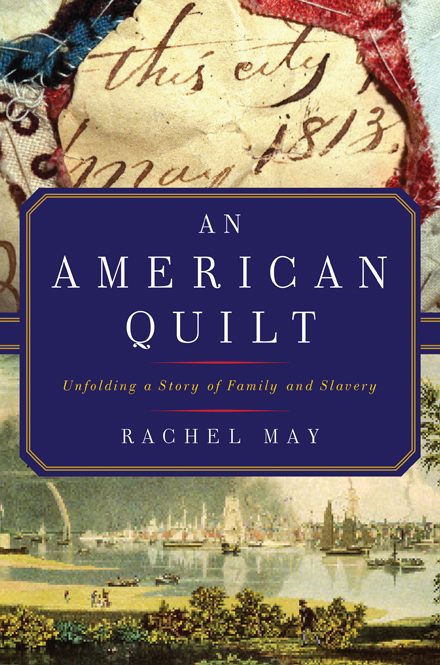

AN AMERICAN QUILT

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2018 by Rachel May

First Pegasus Books cloth edition May 2018

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Images in the book are used with permission. Reproduction is prohibited without permission from the image rights holders.

Any unattributed photos are copyright of the author and cannot be reproduced without permission.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-68177-417-6

ISBN: 978-1-68177-478-7 (e-book)

Distributed by W. W. Norton & Company

www.pegasusbooks.us

T here is the sound of a baby in the house, a delight. He is a fat baby, a happy baby, full of laughter and mischief, Susan writes. The light falls through the window of their house on Cumberland Street each morning, when the baby wakes her early, and she gazes at him and makes him smile. Touches his sweet, soft skin. Leans toward him to kiss him and linger at his cotton-soft tendrils of hair. He is always getting into things; she cant turn away from him for a moment. He kicks his father in bed at night, and in the morning, they laugh about it togetherhis kicks are no joke! But he is so easy at bedtime, going off to sleep contented. Susan is a mother for the first time at twenty-three. Come for a visit, she tells her sisters in letter after letter. Come and see my baby. Hes such a good baby, she tells them, hes so easy.

She is proud. She has gone to housekeeping with her new young husbandnow a doctor, no less. Their life is a delight.

She is an expert sewer, and when the baby goes to bed each night, she bends over her hexagons, basting them one after the other with swift, quiet stitchesand her husband sits and thinks to the sound of thread running through cloth and paper. He thinks about the patients he saw that day, some of their cases simplerheumatism, a coldwhile others were intricate puzzleschronic stomach pain, headaches, an inexplicable bulge in ones side. Susan hands him a hexagon, and he sews. Hes designed the pattern, and together, they make the quilt that Id come to know almost two hundred years later.

In 1833, when Susan was twenty, there were pelerine collars on dresseswhat wed call boat neck collar today, straight across the breastline with the collarbones exposed. There were leg o mutton sleeves, poofed at the top, slender at the wrist. There were bonnets with bows and feathers. When the head was bare, a womans do was two puffs at each side of her face, and a single high twisted bun at the top. It reminds me of a primped samurai. Susan must have worn this look in her early twenties.

But first. Imagine: In 1820, Susan is seven. Her mother will cut the vegetables brought in by Susans brothers from the kitchen garden, stoke the fire in the iron stove, dice the beef. Unlike her wealthier neighbors, she doesnt have a girl to help. She has boarders to feeda family staying the night between Boston and Newport and two Brown University students. Sometimes, she has more than twenty boarders. Shell come to Susan to look at the sampler, examine her stitches to see if theyre fine enough. How is the arch of the lowercase a? How straight is the line of the y? Susan has made three alphabets this week, and then shell start the phrase her mother dictated to her this morning: Behold the child of innocence how beautiful is the mildness of its countenance and the diffidence of its looks. Maybe Sarah Rose, her mother, stitched the same when she was a child. Its Sarah Roses jobas it will be Susansto make the coverlets, the quilts, the dresses, the petticoats, the corsets, the pantaloons, the trousers, and the jackets. Sarah Roses family depends upon her skill to keep them clothed, warm, respectable, and in fashion. Their clothes, the stitched objects in their home, signify their class and status in this world, and influence every element of their lives, from love to business. Susan has been sewing since she was three.

Next, she cross-stitches the phrase Be good and be happy. She makes the red stitches in xs across the linen, carefully pressing the needle in and out, piercing the white cloth at the top and bottom of each x until shes built a B out of what feels like a hundred small xs. And then the e, and so on. Her mother is satisfied with her stitches. She does not ask Susan to tear them out. They remain.

One hundred years later, Susans grandnephew Franklin would find this sampler, along with three quilt tops, in a trunk that traveled from Charleston back to Providence and remained sealed shut after Susans heartbreak. Franklin would be the first to examine its contents in almost a hundred years, and I would be the first to fall in love with the quilt and its story after he passed away, another near-century later.

On the first day, before I even saw the quilt tops, I was captured by their mystery, my sense of the secrets they must hold and the knowledge that Id get to touch the cloth and study hundreds of paper templates made from ephemera. As a quilter and writer seduced by the tactile and drawn to a good story, I approached them with wonder and delight. I was finishing a book on modern quilting and lived in a Rhode Island house built in 1738; it was rumored that George Washington stayed at this house in Little Rest on his way down to Delaware in the 1781. Id walk across the original wide pine floorboards in my apartment, the sound of squirrels chuckling in the walls throughout the winter, trying to imagine who else had walked these floors, if I might be walking in Washingtons ghostly trace.

When Prof W. mentioned these quilt tops I might study as part of a material culture theory course, I was intrigued. We knew only that they were made by a newlywed couple in Charleston, South Carolinahe was a doctor who worked on the quilts with his wife when he had a difficult caseand donated in 1952 by a colonial revivalist from Providence. It was a snowy winter day when Prof W. led me down the overheated hall of the Textiles, Fashion Merchandising and Design department at the University of Rhode Island. With a jingling set of keys, she unlocked the old wooden door of the flat-storage room, and once inside, slid open the metal drawer of what looked like a map case. As it opened, I saw the first quilt top, its sky-blue, red plaid, white floral, green zigzag hexagons slowly revealed. My intrigue became entrancement. I couldnt wait to touch it.

Prof W. slid both arms underneath it, gently, as if it were a sickly lamb. The only sound was the crinkle of the tissue paper that had been set between its layers to keep it from pressing against itself in storage. She set it down on top of the case and slid her arms out from underneath.

The papers are fragile in the back, she said. Every time you move them, a few crumbs fall away.

We looked over the front of the quilt, unfolded it once and found a central star of colorful calico hexagons with a white center. And around the star, flowers of hexagons... separated by rows of white hexagons, some of which were yellow and brown with age. The checks, stripes, indigos, chintzes, calicos, drabs, and rainbow prints dazzled me. There were white parrots heads framed in repeating hexagons around a central patch of red, sweet red ginghams and plaids, a pink floral print on a white background.

Next page