to my parents, and my children, and to Joseph

When the thought of New England is regarded not from a New England or even from an American point of view, but is seen as what in truth it was, a part, and an important part, of the whole thought of the seventeenth century, exemplifying the essential characteristics and struggling with the most importunate problems of the epoch, then and only then can both the provincial and European scene be illuminated.

Perry Miller, The New England Mind: The Seventeenth Century

CONTENTS

New England Bound is based on seventeenth-century sources. In order not to lose the sense of a world that had irregular spelling, grammar, and punctuation, quotations remain as they appear in the original text, except that superscript letters have been lowered, and abbreviations that would not be intelligible to the modern reader have been expanded or spelled out. Readers may find that passages that seem opaque become clearer if they are read out loud, as was indeed the practice of many early modern readers. All dates have been aligned with the modern calendar, with the year beginning on January 1.

Biblical passages cited in the following pages are from the King James Bible (KJV). While the Geneva Bible could be found throughout the colonies, English Puritans in New England largely preferred the KJV, or Authorized version.

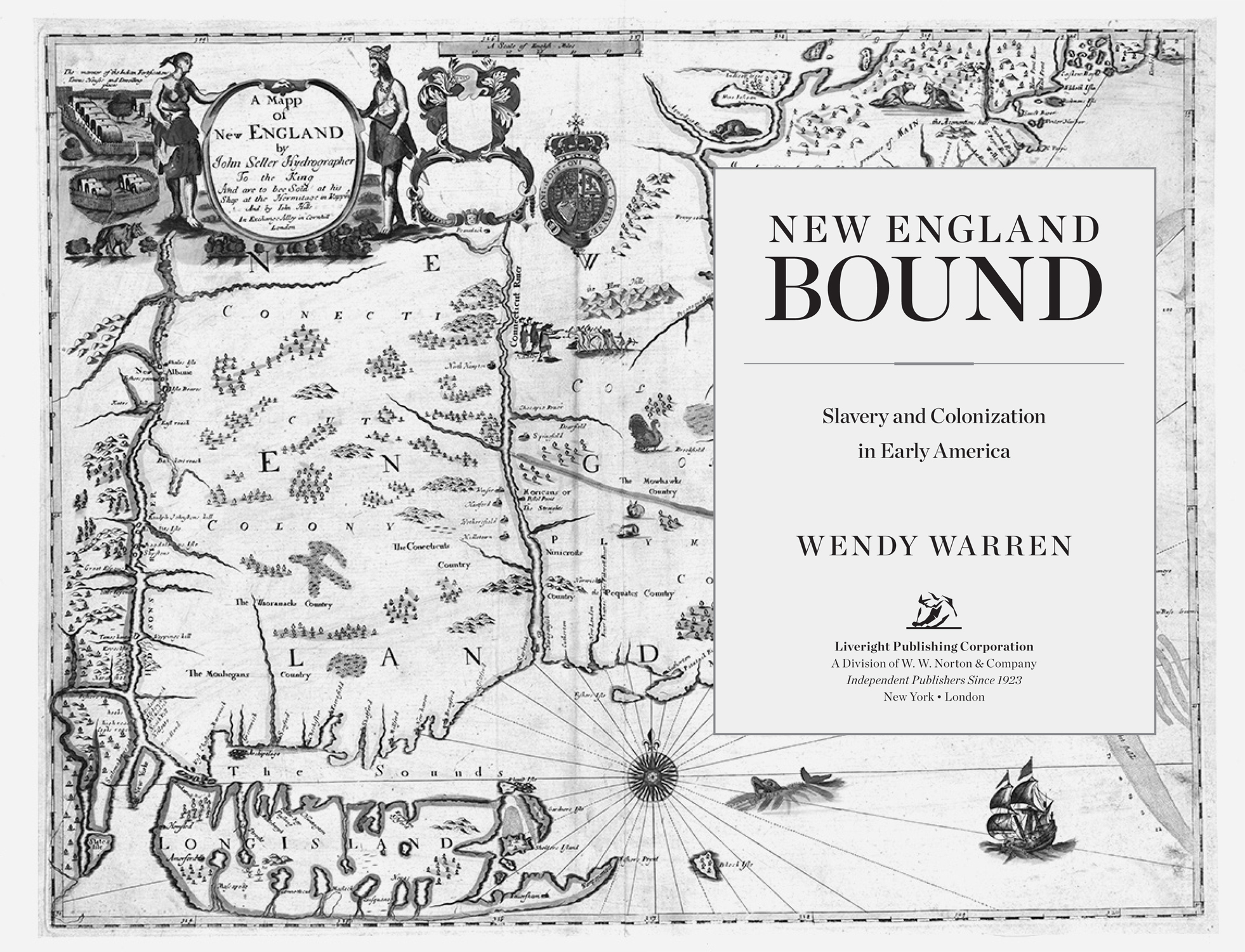

NEW ENGLAND

BOUND

The Cause of Her Grief

For there is not a just man upon earth, that doeth good, and sinneth not.

Ecclesiastes 7:20

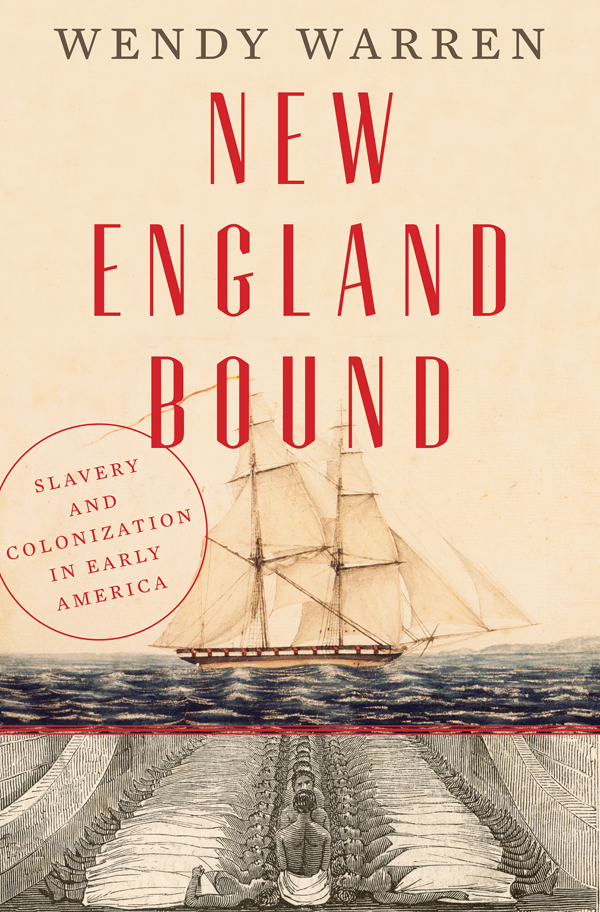

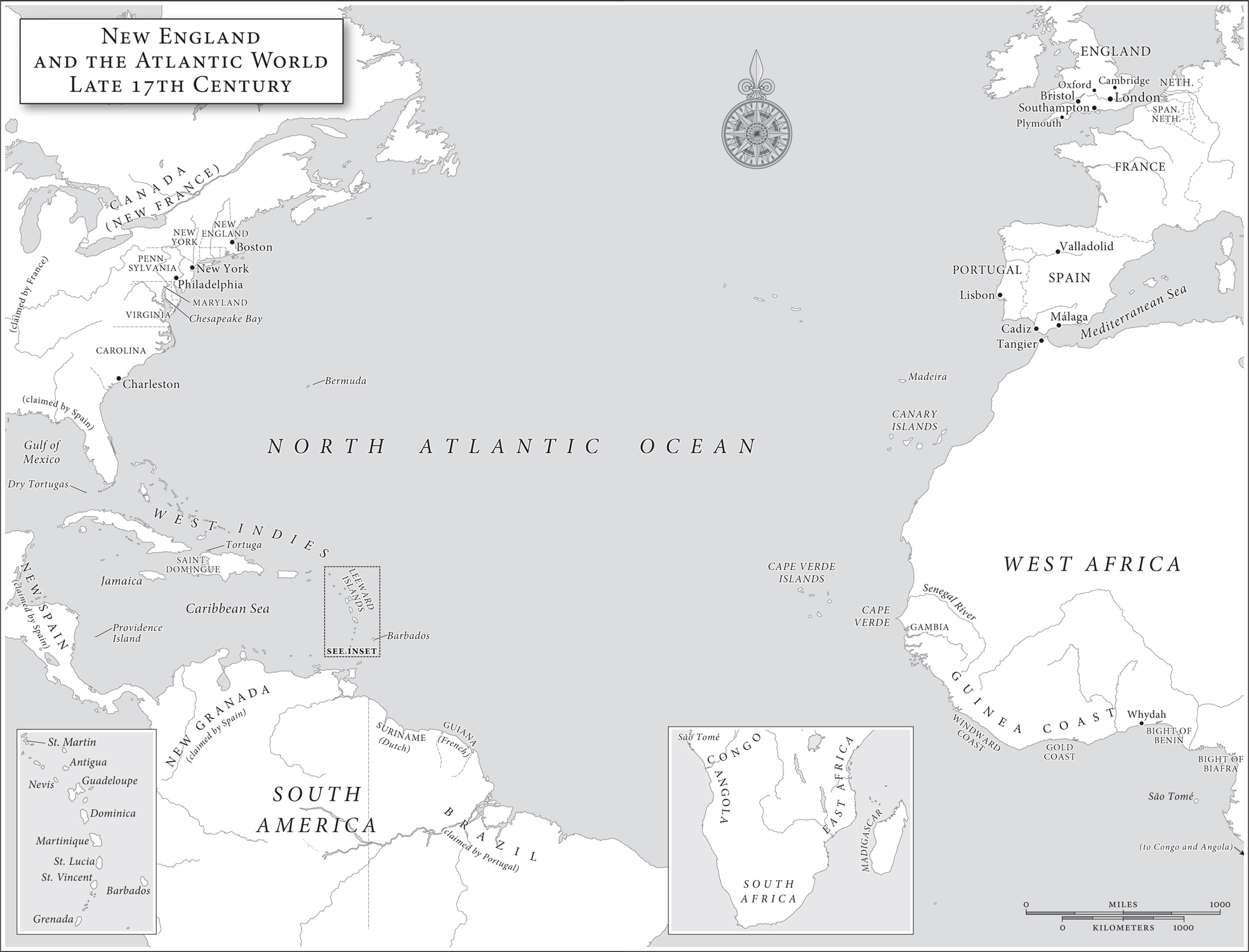

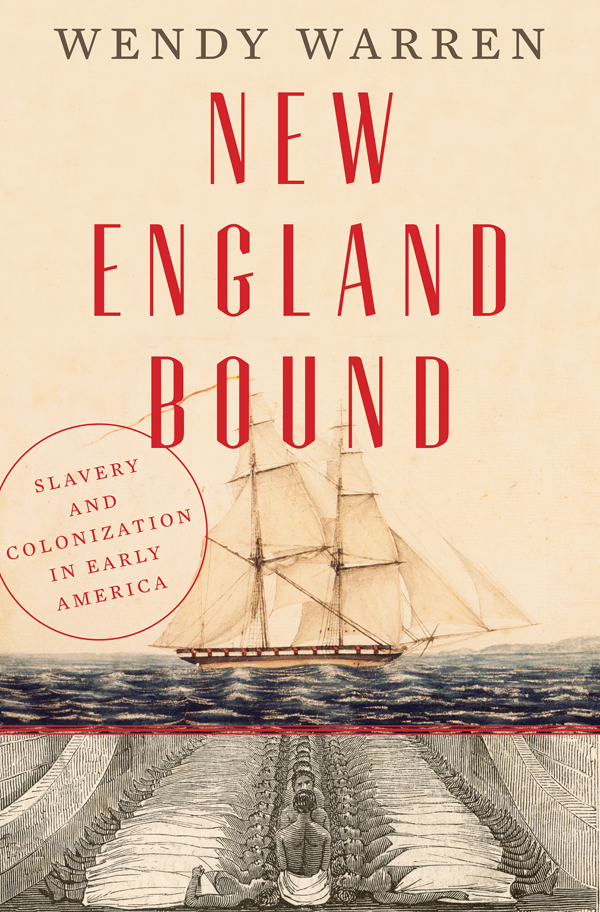

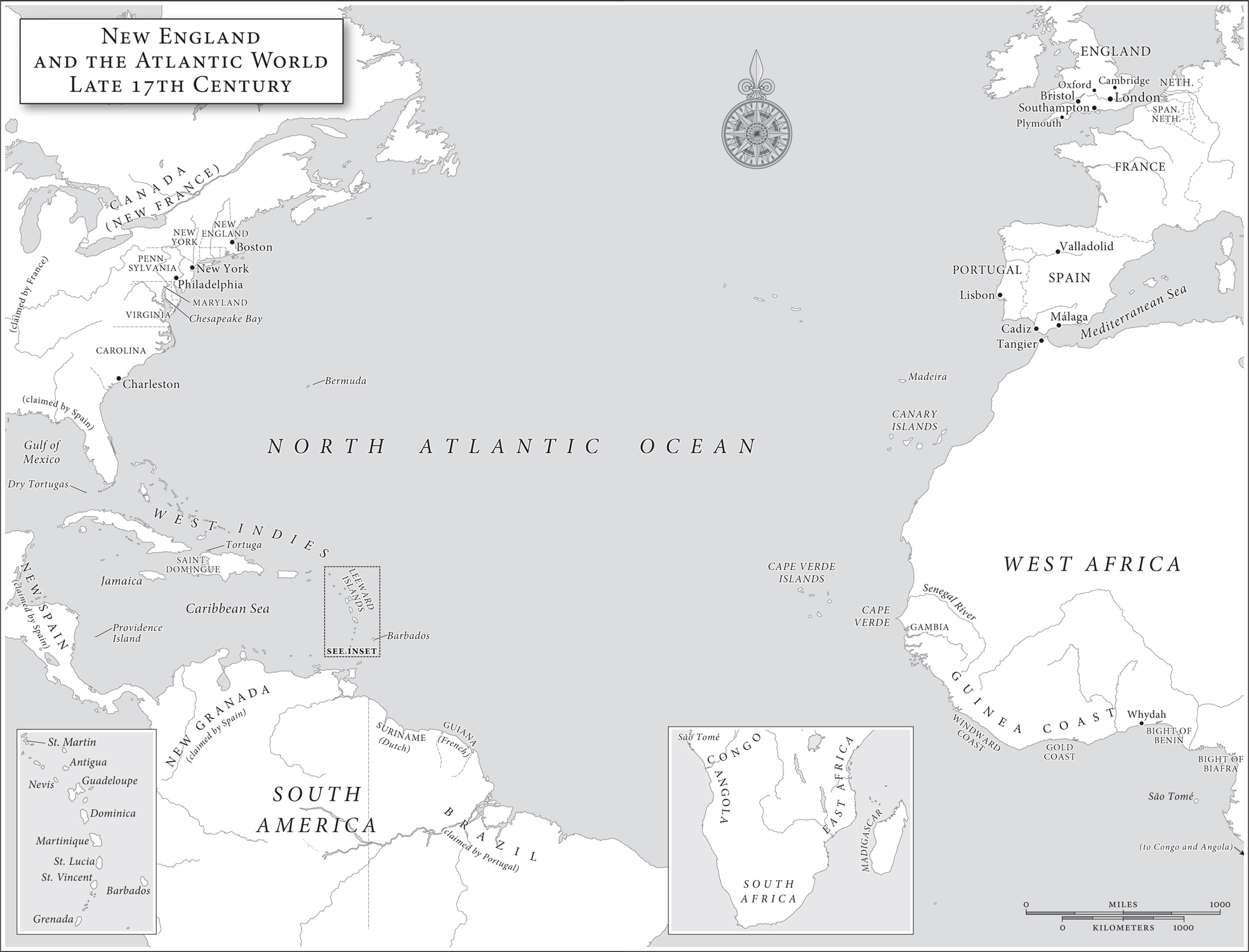

T his is a book about two of historys most violent enterprises: slavery and colonization. Both of these problems of course continue to afflict the world, but in the centuries following the Columbian discovery, they were among its most prevalent features. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, a period that roughly coincides with the colonial periods of North and South America, nearly thirteen million Africans were enslaved and shipped west across the Atlantic, while two to four million Native Americans were enslaved and traded by European colonists in the Americas. In fact, though, this pairing was no coincidence. Slavery and colonization went hand in hand. Without colonies to grow staple crops like sugar, rice, and tobacco, and to proffer wealth in the form of valuable minerals, there would have been much less need for slaves. Without Indian and African slaves, there would have been no labor to grow the crops or to extract those mineralsat least not labor cost-efficient enough to create the profits that made the whole system viable. It was a deadly symbiosis.

That symbiosis fostered the European colonization of all the Americas, including a small region known as New England, a cluster of colonies perched on the edge of Englands fledgling North American empire. Colonized in the early seventeenth century by stern people wearing black hats and somber clothes, the popular story goes, New England became an exceptional land of hard work and bountiful crops and thrift and curtness and fervent religiosity. Puritans, we call these fabled people, a sort of shorthand used to describe a motley array of Protestants interested in reforming a Church of England they considered too encumbered by vestiges of Roman Catholicism.

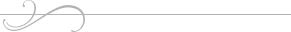

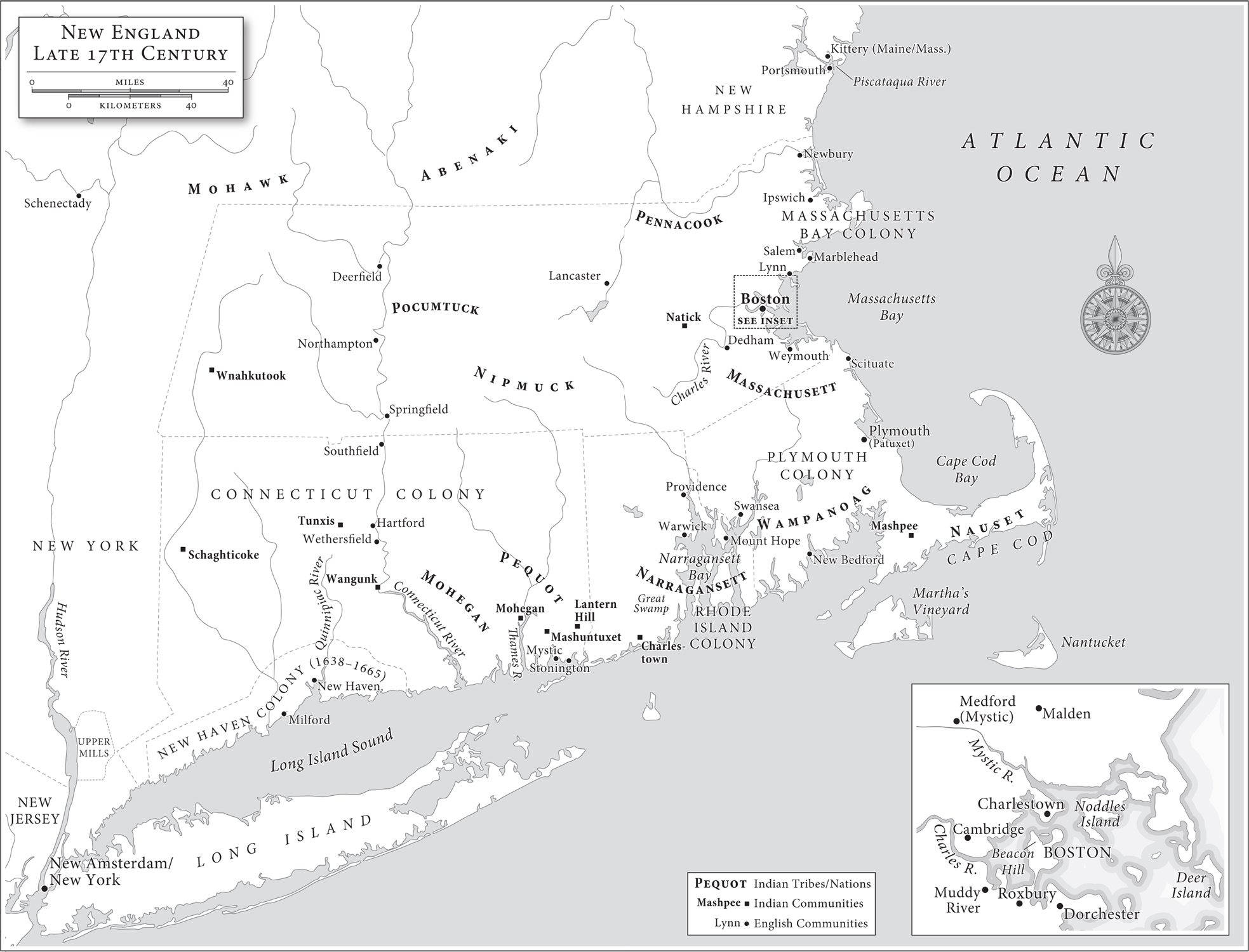

Between the years 1620 and 1640 alone, more than twenty thousand English colonists emigrated to the northeastern coast of North America, where they founded in quick succession the colonies that would become jointly known as New England: in 1620, Plymouth (a colony that later joined with Massachusetts); in 1630, the Massachusetts Bay Colony; in 1636, the colonies of Connecticut and of Rhode Island; in 1637, the New Haven Colony (eventually joined to Connecticut). Some of these colonists were Separatists (that is to say, they sought to separate totally from the Church of England), while some were considerably less radical, but most shared a dissatisfaction with the current state of affairs in English society. In New England they famously, even infamously, sought to live in ways that more closely hewed to a notion of spiritual purity than seemed possible to them in Englandthey established more than forty meetinghouses in the first two decades alone. By the end of the century, the New England colonies were established, even thriving.

But more than the spirit moved English colonists who went to New England. In fact, historians in recent decades have told a more complicated story, one that highlights how the famed devotion of these colonists coexisted with their very real pecuniary desires, how piety and profit worked hand in hand in the region. And scholars have also long pointed out that English colonists were not all Puritan, and that the English were not the only characters in the story. More recent narratives have emphasized that native people in the region played an equal and crucial role in the colonial encounter, trading commercial goods, religious visions, and agricultural practices with the English, and also warring with them, all groups vying for control of the regions plentiful land and propitious waters. In these ways, the colonization of New England has come to seem more like the colonization of the rest of the Americas.

And yet, even as our understanding of the colonial process in the region has grown more complicated, there has remained something exceptional in both the popular and the scholarly understanding of early colonial New England, an exceptional absence. Put plainly, it is this: the tragedy of chattel slaveryinheritable, permanent, and commodified bondagethe problem that dominates the narrative of so many other early English attempts at colonization in North America and the Caribbean, hardly appears in the story of earliest New England. The following pages demonstrate why it should.

Next page