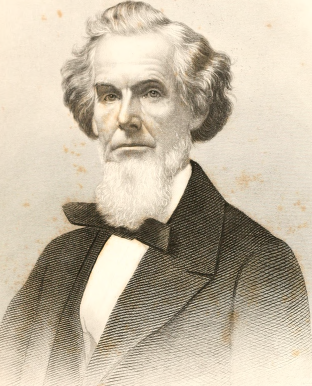

Cotton is king, and pro-slavery arguments: comprising the writings of Hammond, Harper, Christy, Stringfellow, Hodge, Bledsoe, and Cartwright, on this important subject

Elliott, E. N., ed

Christy, David, b. 1802

Bledsoe, Albert Taylor, 1809-1877

Stringfellow, Thornton

Harper, William, 1790-1847

Hammond, James Henry, 1807-1864

Cartwright, Samuel Adolphus, 1793-1863

Hodge, Charles, 1797-1878

This book was produced in EPUB format by the Internet Archive.

The book pages were scanned and converted to EPUB format automatically. This process relies on optical character recognition, and is somewhat susceptible to errors. The book may not offer the correct reading sequence, and there may be weird characters, non-words, and incorrect guesses at structure. Some page numbers and headers or footers may remain from the scanned page. The process which identifies images might have found stray marks on the page which are not actually images from the book. The hidden page numbering which may be available to your ereader corresponds to the numbered pages in the print edition, but is not an exact match; page numbers will increment at the same rate as the corresponding print edition, but we may have started numbering before the print book's visible page numbers. The Internet Archive is working to improve the scanning process and resulting books, but in the meantime, we hope that this book will be useful to you.

The Internet Archive was founded in 1996 to build an Internet library and to promote universal access to all knowledge. The Archive's purposes include offering permanent access for researchers, historians, scholars, people with disabilities, and the general public to historical collections that exist in digital format. The Internet Archive includes texts, audio, moving images, and software as well as archived web pages, and provides specialized services for information access for the blind and other persons with disabilities.

Created with abbyy2epub (v.1.7.2)

THE EISENHOWER LIBRARY

3 1151 02744 0837

MILTON S. EISENHOWER

LIBRARY

OF

THE JOHNS HOPKINS

UNIVERSITY

There is now but one great question dividing the American people, and that, to the great danger of the stability of our government, the concord and harmony of our citizens, and the perpetuation of our liberties, divides us by a geographical hne. Hence estrangement, alienation, enmity, have arisen between the North and the South, and those who, from " the times that tried men's souls," have stood shoulder to shoulder in asserting their rights against the world; who, as a band of brothers, had combined to build up this fair fabric of human liberty, are now almost in the act of turning their fratricidal arms against each other's bosoms. All other parties that have existed in our country, were segregated on questions of policy affecting the whole nation and each individual composing it ahke; they pervaded every section of the Union, and the acerbity of political strife was softened by the ties of blood, friendship, and neighborhood association. Moreover, these parties were constantly changing, on account of the influence mutually exerted by the members of each; the Federalist of yesterday becomes the Republican of to-day, and Whigs and Democrats change their party allegiance with every change of leaders. If the republicans mismanaged the government, they suffered the consequences alike with the federalists; if the democrats plunged our country into difficulties, they had to abide the penalty as well as the whigs. All parties ahke had to suffer the evils, or enjoy the advantages of bad or good government. But it has been reserved to our own times to witness the rise, growth, and prevalence of a party confined exclusively to one section of the

Union, whose fundamental principle is opposition to the rights

(iii)

IV

INTRODUCTION,

and interests of the other section; and this, too, when those rights are most sacredly guaranteed, and those interests protected, by that compact under which we became a united nation. In a free government hke ours, the eclecticism of partiesby which we mean the affinity by which the members of a party unite on questions of national policy, by which all sections of the country are aUke affectedhas always been considered as highly conducive to the purity and integrity of the government, and one of the causes most promotive of its perpetuity. Such has been the case, not only in our own country, but also in England, from whom we have mainly derived our ideas of civil {ind religious liberty, and even, to some extent, our form of government. But there, the case of oppressed and down-trodden Ireland, bears witness to the baneful effects of geographical partizan government and legislation.

In our own country this same spirit, which had its origin in the Missouri contest, is now beginning to produce its legitimate fruits: witness the growing distrust with which the people of the North and the South begin to regard each other; the diminution of Southern travel, either for business or pleasure, in the Northern States; the efforts of each section to develop its own resources, so as virtually to render it independent of the other; the enactment of " unfriendly legislation," in several of the States, towards other States of the Union, or their citizens; the contest for the exclusive possession of the territories, the common property of the States ; t^e anarchy and bloodshed in Kansas; the exasperation of parties throughout the Union; the attempt to nullify, by popular clamor, the decision of the supreme tribunal of our country; the existence of the "underground railroad," and of a party in the North organized for the express purpose of robbing the citizens of the Southern States of their property; the almost daily occurrence of fugitive slave mobs; the total insecurity of slave property in the border States;*

* Strange that we should be compelled to call those border States, which lie in the very midst of our Union.

the attempt to circulate incendiary documents among the slaves in the Southern States, and the flooding of the whole country with the most false and malicious misrepresentations of the state of society in the slave States; the attempt to produce division among us, and to array one portion of our citizens in deadly hostility to the other; and finally, the recent attempt to excite, at Harper's Ferry, and throughout the South, an insurrection, and a civil and servile war, with all its attendant horrors. All these facts go to prove that there is a great wrong somewhere, and that a part, or the whole, of the American people are demented, and hurrying down to swift destruction. To ascertain where this great wrong and evil lies, to point out the remedy, to disabuse the public mind of all erroneous impressions or prejudices, to combat all false doctrines on iJiis subject, and to establish the truth, shall be the aim of the following pages. In preparing them we have consulted the works of most of the writers on both sides of this question, as well as the statistics and history tending to throw Hght upon the subject. To this we would invite the candid and dispassionate attention of every patriot and philanthropist. To all such we would say, in the language of the Roman bard,

" Si quid novisti vectius istis, Candidus imperti; si non, His utere mecum."

In the following pages, tjie words slave and slavery are not used in the sense commonly understood by the abolitionists. With them these terms are contradistinguished from servants and servitude. According to their definitioD, a slave is merely a."chattel" in a human form; a thing to be bought and sold, and treated worse than a brute; a being without rights, privileges, or duties. Now, if this is a correct definition of the word, we totally object to the term, and deny that we have any such institution as slavery among us. We recognize among us no class, which, as the abolitionists falsely assert, that the Supreme Court decided " had no rights which a white man was

Next page