I owe special thanks to Clayborne and Susan Carson, who have been guiding lights and dear friends in the world of King and freedom-movement scholarship for many years. The Martin Luther King, Jr., Papers Project and the MLK Research and Education Institute at Stanford University, led by senior editor Clayborne Carson, associate director Tenisha Armstrong, and others associated with the Institute helped me to find documents and always provided friendship and solidarity in studying the life and legacy of Dr. King. This is a unique group and a special place.

Grateful thanks to Alane Salierno Mason, my editor at W. W. Norton, who read this manuscript several times and saw it through to completion, to Ashley Patrick and Kyle Radler at Norton, to Kenneth OReilly, and to Roz Foster, my agent at the Sandra Dijkstra Literary Agency, who provided marvelous support.

Special thanks to Nancy Bristow, who helped me to get this manuscript to the finish line, Will Jones, Keona Ervin, David Black, Martha Allen, Joseph Rosenbloom, and Roz Foster, friends and colleagues who read all or nearly all of the manuscript and offered much help in how to tell this story. Thanks to Erik Gellman, Aram Goudsouzian, Alan Draper, Anthony DCosta, Robert Korstad, Ray Glantz, Jill Twist, David Smith, Beth Stevens, and Patti Krueger, who read parts of it and offered comments at various stages, and to Charles McKinney. Special thanks as well to colleagues and friends Nelson Lichtenstein and Eileen Boris, David Roediger, Robin D. G. Kelley, Paul Ortiz, Ray Arsenault, Dennis Dickerson, James Gregory, Nancy MacLean, Alice Kessler-Harris, Martha Biondi, Eric Arnesen, Joseph McCartin, Joe Trotter, David Bacon, Lisa Brock, Thavolia Glymph, Kwame Hassan Jeffries, Ira Berlin, Barbara Fields, Marcus Rediker, David Chappel, Nell Irvin Painter, Jacqueline Dowd Hall, Tera Hunter, Keith Miller, Thomas Jackson, Kieran Taylor, and others who have helped me to think about this history. Friendships and discussions with freedom-movement veterans Jack ODell and James Lawson have deeply informed my study of King and nonviolence, as have Kent Wong and his colleagues at the UCLA Labor Center. Beloved mentors and colleagues David Montgomery, Otto Olsen, Henry Rosemont, Jr., Robert Zieger, James Green, Carl and Anne Braden, Lyle Mercer, and faculty and fellow students who taught me at Oakland University, Howard University, and Northern Illinois University history departments all set the stage.

Thanks to the National Civil Rights Museum for its marvelous way of carrying on the freedom-movement story and providing a continuing connection to the Memphis community. Thanks to colleagues and friends Mark Allen and Cheryl Cornish, Steve Lockwood and Mary Durham, David Ciscel, and Anthony Siracusa, who continue to make Memphis a second home; to Daphene McFerrin and Elena Delavega at the Ben Hooks Institute, Wanda Rushing, David Ciscel (emeritus), Wendy Thomas, and Otis Sanborn at the University of Memphis for their research insights; and to Kevin Bradshaw, Tom Smith, A. C. Wharton, Gail Tyree, Mar Perrusquia, and Kay Davis for generous insights on labor and civil rights in Memphis today.

Thanks for generous research help on this project from Suzanne Klinger, our extraordinary history librarian at the University of Washington Tacoma, and to students and former students Olga Subbotin, Richard Agee, Kelvin Wong, Daniel Twigg, Lucas Dambergs, Adam Nolan, Kyle Veldhuizen, and to Keith Ward and Randy Hightower. And to Turan Kayaoglu, and my many colleagues at the University of Washington Tacoma who continue to support research, teaching, and community outreach. Special thanks to the family of Fred and Dorothy Haley and to the Haley professorship for making a continuing life of research and writing possible. Grateful thanks to Kathy Cowell and the Arthur and Helen Riaboff Whiteley Center and UW Marine Labs in Friday Harbor, Washington, for supporting my writing retreats, and to Ray Glantz and Sandy Rabinowitz for their loving hospitality. The Harry Bridges Chair and Center for Labor Studies has provided a wonderful home for me at the University of Washington, and I thank all my friends and union allies, particularly members of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU), the University of Washington Faculty Forward, and American Association of University Professors. I am thankful also for a Guggenheim fellowship that provided time to think about this project as I wrote my book about John Handcox, the Sharecroppers Troubadour.

The Martin Luther King, Jr., Papers at the Martin Luther King, Jr., Center for Nonviolent Social Change, Atlanta, Georgia; the Walter Reuther Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs at Wayne State University, Detroit; the FBI records on Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Memphis sanitation strike; the AFL-CIO Papers, now at the University of Maryland, College Park; the Sanitation Strike Collection at the Mississippi Valley Collection at the University of Memphis McWherter Library; clipping files and manuscript collections of the Memphis Public Library, with generous help by Wayne Dowdy; the James Lawson Papers at Vanderbilt University; and the A. Philip Randolph Papers at the Library of Congress Manuscripts Collection all have been important sources for my research.

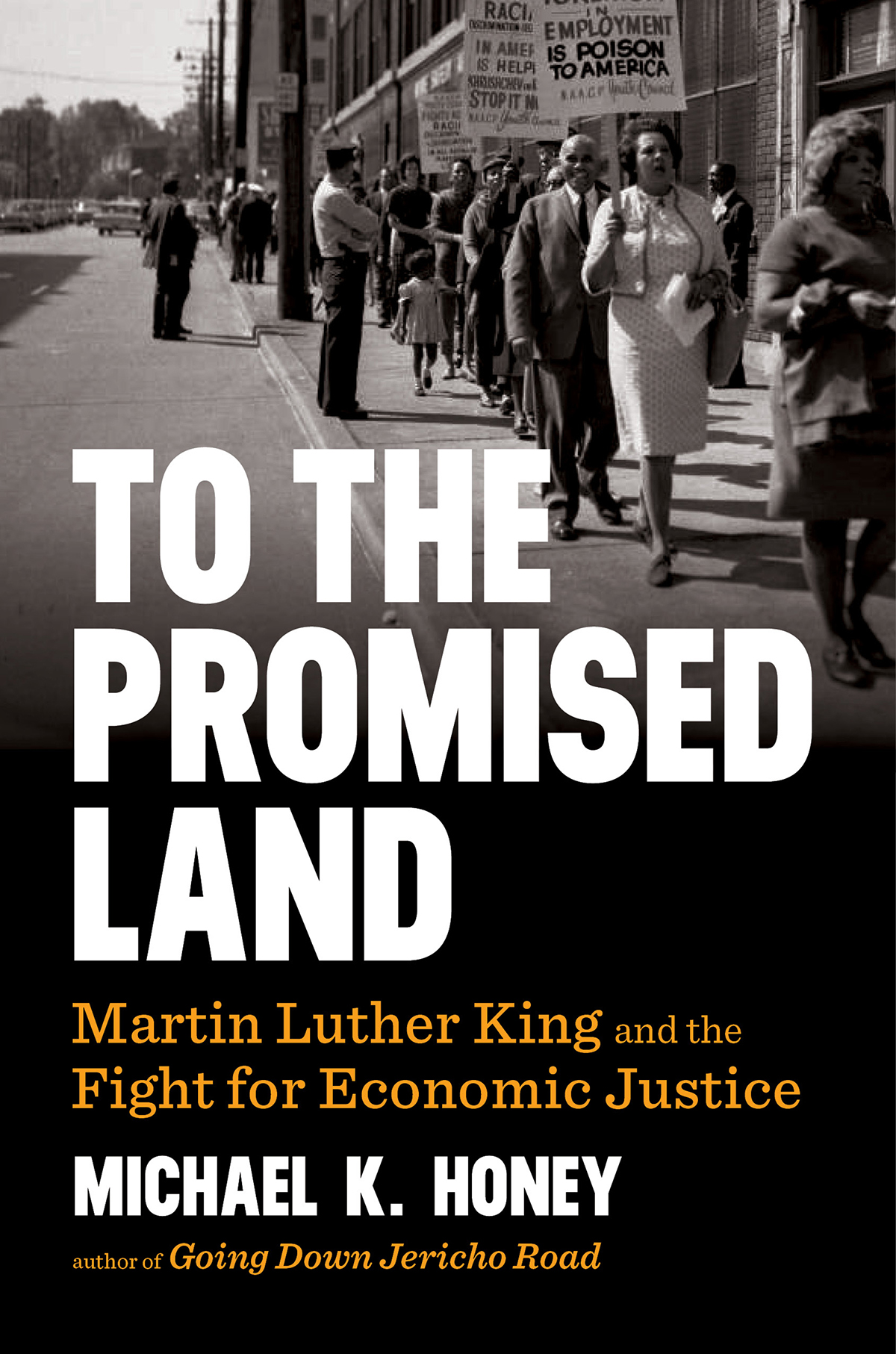

Richard Copley, Bob Fitch, and others have provided extraordinary photos. My thanks also to friends and colleagues in the Labor and Working Class History Association, the Southern Historical Association, the Organization of American Historians, and the Southern Labor Studies Association. There are many more people to thank for making real the possibility of being a freedom movement and labor-history scholar.

Special thanks to my partner in life, Patti Krueger, whose steadfast love makes all things possible; to my brother Charles Honey and sister Maureen Honey; and to all the people in our extended Krueger, Allen, and Miner families whose love and solidarity keep us all strong.

OTHER WORKS BY MICHAEL K. HONEY

Books

Sharecroppers Troubadour:

John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers Union,

and the African American Song Tradition

Going Down Jericho Road:

The Memphis Strike, Martin Luther Kings Last Campaign

Black Workers Remember:

An Oral History of Segregation, Unionism, and

the Freedom Struggle

Southern Labor and Black Civil Rights:

Organizing Memphis Workers

Film

Love and Solidarity:

James M. Lawson and Nonviolence in the

Search for Workers Rights

Edited Work

Martin Luther King, Jr., All Labor Has Dignity

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michael K. Honey is the author of the Robert F. Kennedy Book Awardwinning Going Down Jericho Road: The Memphis Sanitation Strike, Martin Luther Kings Last Campaign (2007), which also received the Liberty Foundation Legacy Award from the Organization of American Historians (OAH), the H. L. Mitchell Award from the Southern Historical Association (SHA), and University Association of Labor Educator and International Labor Research Association best book awards. Honeys other books include Sharecroppers Troubadour: John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, and the African American Song Tradition (2013); Black Workers Remember: An Oral History of Segregation, Unionism, and the Freedom Struggle (1999), winner of the Lillian Smith Book Award from the Southern Regional Council and the H. L. Mitchell Award (SHA); and Southern Labor and Black Civil Rights: Organizing Memphis Workers (1993), winner of the Charles S. Sydnor Award (SHA) and the James A. Rawley Prize (OAH). He edited a volume of Martin Luther King, Jr.s speeches, All Labor Has Dignity

Next page