Chapter One

A SIMPLE REQUEST

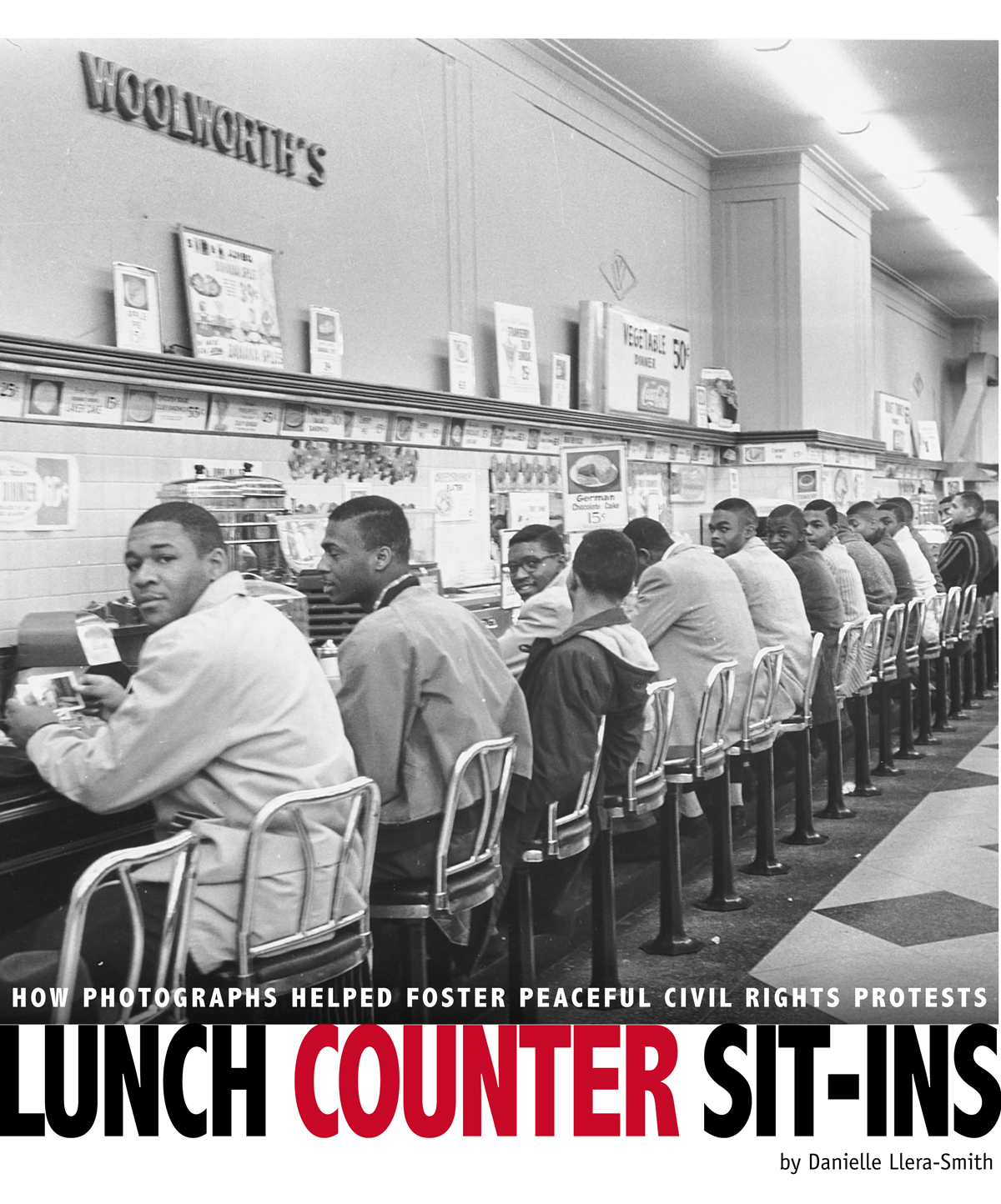

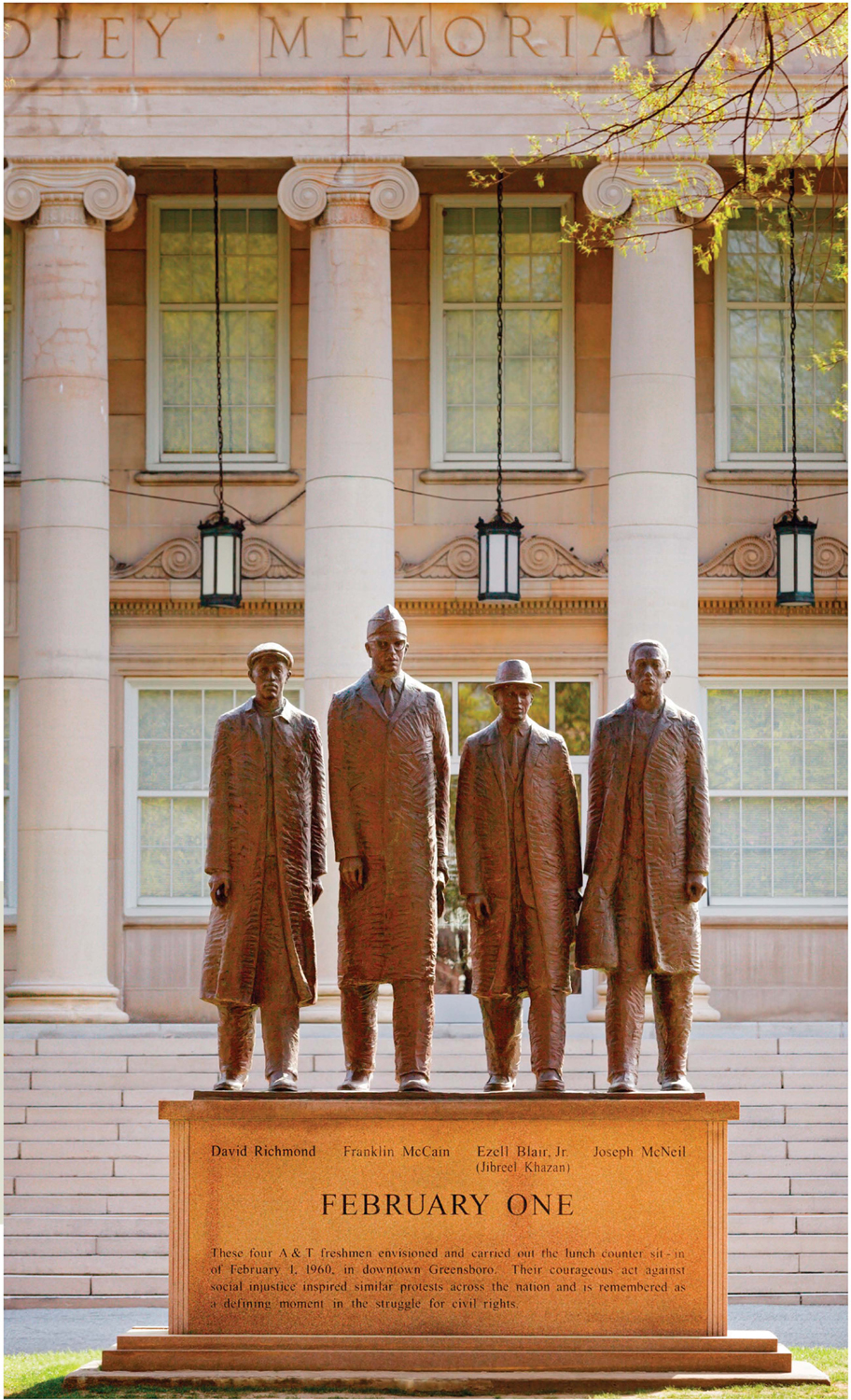

When four young men planned a lunch counter sit-in, the last thing on their minds was the thought that, one day, there would be a monument to them.

Four young men arrived at the

Blairs friend slavery.

McNeils friends shared his frustrations. For two weeks they debated relentlessly what to do. On January 31 they came up with a plan. Are you chicken?Richmond said he was in. Blair was reluctant at first. But when McCain held a vote, four hands went up. The foursome were now united in their mission.

The four young men met in front of the A&T campus library the next afternoon, February 1, 1960. They dressed for their mission in their best clothes. McCain wore his Air Force ROTC uniform. They walked downtown through a city divided by race. Their own school had been founded in 1891 to keep black students from entering all-white North Carolina State University. The lives of Greensboros black and white residents rarely overlapped. Black citizens squeezed into cramped houses in the southeastern neighborhoods of the city where they attended their own churches and schools. White people filled neighborhoods of more expensive houses on the citys northwest side. Both communities frequented stores in Greensboros busy downtown, but many displayed signs reading We serve white customers only. Blacks and whites could not sit together in restaurants or movie theaters, or share bathrooms or water fountains.

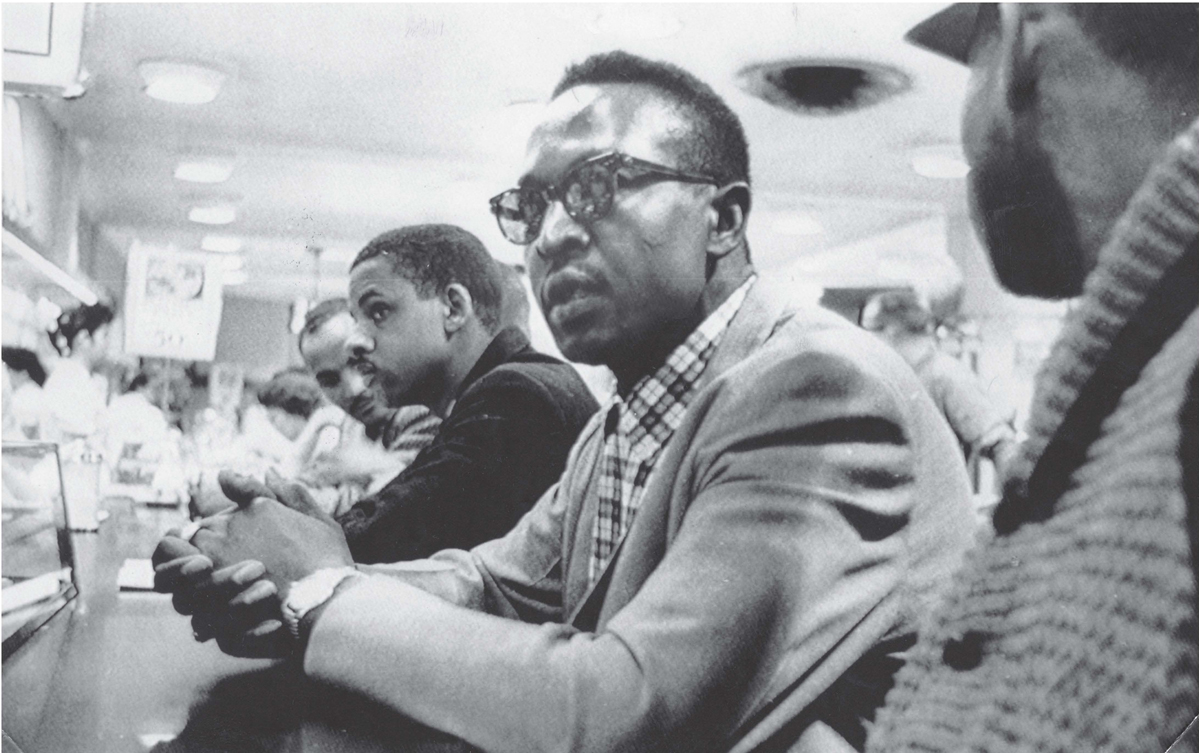

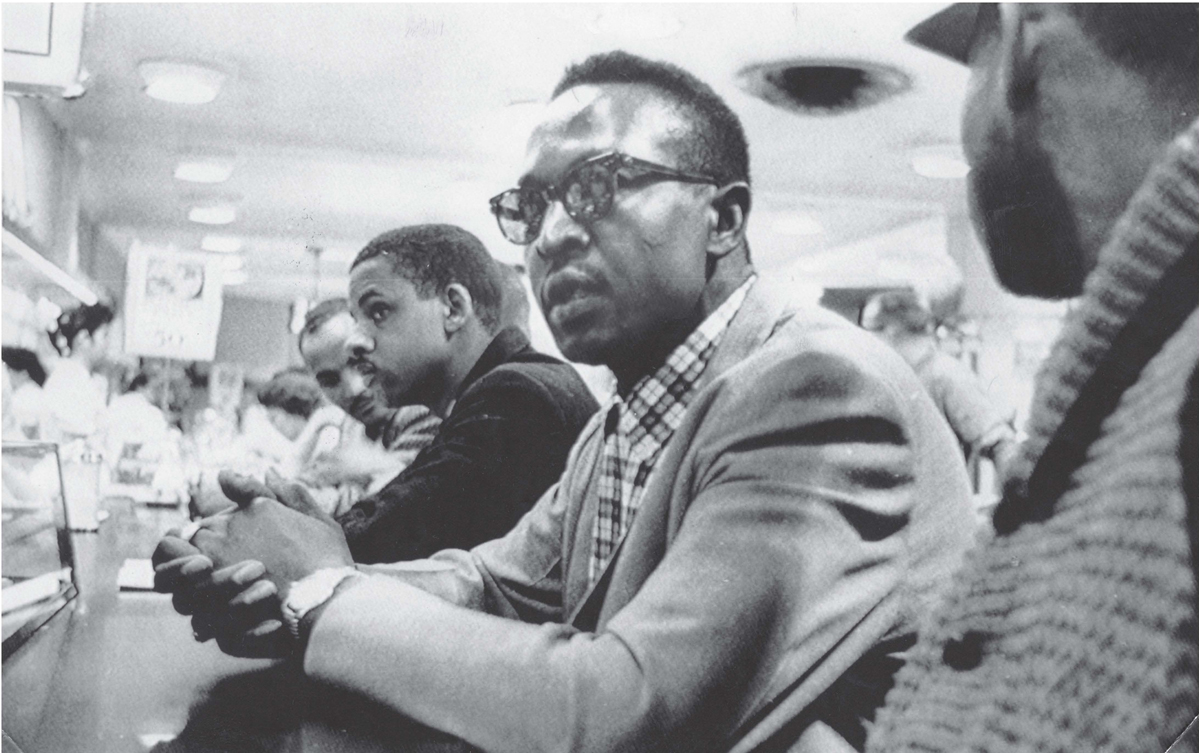

The students who sat at the segregated lunch counters were brave. They were also nervous about what might happen.

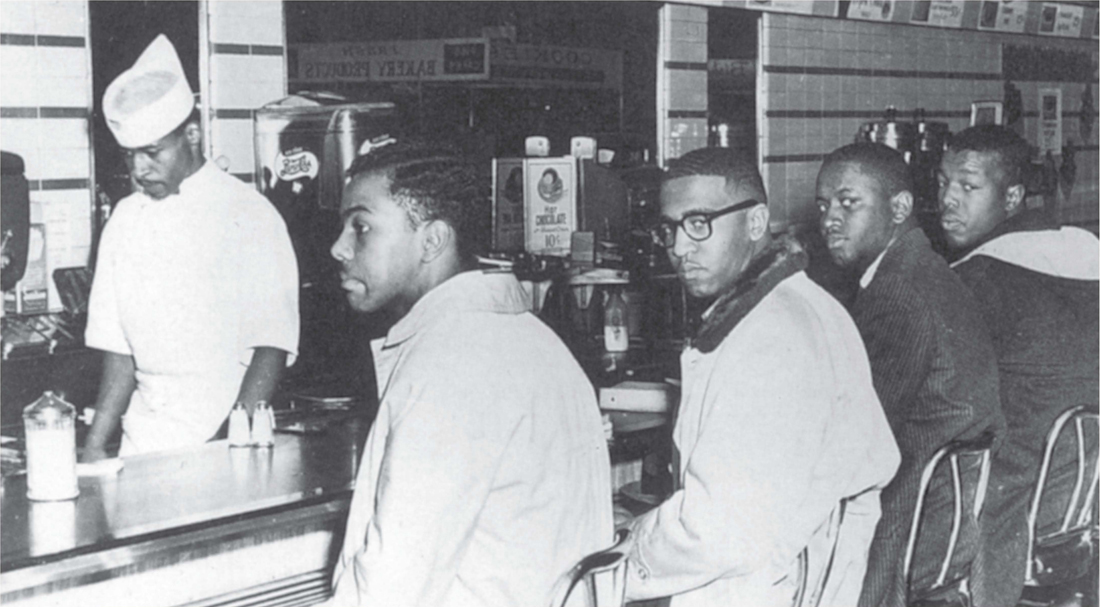

The men arrived at their destination: a popular two-story store called Woolworths. Its large, inviting windows displayed merchandise. The four men knew black customers were welcome to shop. They also knew that black customers were not allowed at the 66-seat lunch counter. Lunch counter service was reserved for white customers.

As planned, the young men bought a few items in the store and then headed for the lunch counter. They sat down on the vinyl-covered stools and ordered pie and coffee. The waitress refused to serve them. They showed their purchase receipts to prove they deserved to be served like other customers. White customers around them grew quiet. The men had set a drama in motion and no one knew what would happen next. The men stayed on their stools, their legs quaking.

The original Woolworths lunch counter is now housed in a civil rights museum.

A black employee appeared from the kitchen. She knew that segregation ruled the

Lunch counter manager Clarence Harris instructed the waitresses to ignore the men and headed for the police station. Police Chief Paul Calhoun told him that he could only arrest the men if Harris accused them of trespassing. But Harris decided that he would only do that if the protest turned violent. Calhoun did send police officers to monitor the unpredictable situation. They paced behind the lunch counters stools, tapping their police clubs in their palms.

Returning to Woolworths frustrated and without a solution, Harris encountered another problem this one just outside the store. Greensboro Record photographer Jack Moebes hoped to get inside with his camera. Harris covered the cameras lens with his hands and ordered Moebes to stay out. Harris closed the lunch counter early and turned off the lights. The four young men marveled that they had not been arrested. They vowed to return. Around 6 p.m. Moebes photographed the four friends walking back to campus side-by-side.

The four friends returned with 16 other

That night the student protesters prepared a letter to Woolworths president. They asked him to take a firm stand to eliminate this had about 1,000 stores in the U.S., Europe, Africa, and the Caribbean.

Woolworths headquarters let its stores follow local customs even if that policy allowed stores in the southern U.S. to discriminate against black customers. Support for segregation there was strong. By the third day of the sit-in, white people supporting segregation rushed to Woolworths early to try to occupy the stools before the protesters could do so.

This photo by Jack Moebes captured the four young men at the lunch counter.

More protesters packed the lunchroom daily, growing to 300 in less than a week. Supporters of segregation taunted them with About 1,000 people now packed the store in an uneasy mixture of students, journalists, police officers, and undercover detectives. Others watched outside through store windows. A bomb threat sent frightened people rushing from the store on the sixth day.

Woolworths closed the lunch counter, which just a week earlier had served 2,000 meals a day. Other Greensboro businesses were losing money too. Student leaders had organized increasing numbers of protesters and taken over other downtown lunch counters. The mayor and business owners had no choice but to meet with black student leaders. Months of difficult negotiations lay ahead.

News and images of the Greensboro Four had spread well beyond the city, and, as the news spread, more black students across the South put on their best clothes to take stools at local segregated counters. Ninety miles (145 kilometers) south of Greensboro, Bruce Roberts of Charlotte, North Carolina, would capture the shot of a first-day sit-in because of a tip from a northern source.

When the telephone rang on February 9, 1960, Roberts was the only photojournalist in the office of the North Carolina newspaper, the Charlotte Observer. Ray Mackland, an editor with Life magazine in New York City, was calling with an exciting tip. Mackland told him a sit-in was about to start at the local Woolworths lunch counter. Roberts newspaper gave its prize-winning photographers freedom to do independent projects. Roberts stuffed six rolls of film into his pockets, grabbed his Nikon 35mm camera and lenses, and dashed out the door. He ran most of the two blocks to the Woolworths store in Charlotte so as not to miss the sit-in.

The night before, 21-year-old He announced a plan: They would order lunch at Woolworths segregated lunch counter. When more than 200 students volunteered, Jones organized an ambitious protest in eight downtown Charlotte locations at once.

Roberts was astonished to see no crowds gathered. A fire truck was parked nearby, but the firefighters were lounging casually. He rushed into the lunchroom, aiming his wide-angle lens at the long room of seated protesters. Worried that a manager would throw him out, Roberts quickly shot a roll of film, popped it out of the camera, and stashed it safely in his pocket.

Looking around, he realized the entire staff seemed to have left. That meant managers, waitstaff, and cooks. Only the protesters remained, waiting peacefully to see what would happen.stores across the city of Charlotte.