Copyright 2018 by Sheila Pree Bright.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 9781452170848 (epub, mobi)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bright, Sheila Pree, Photographer.

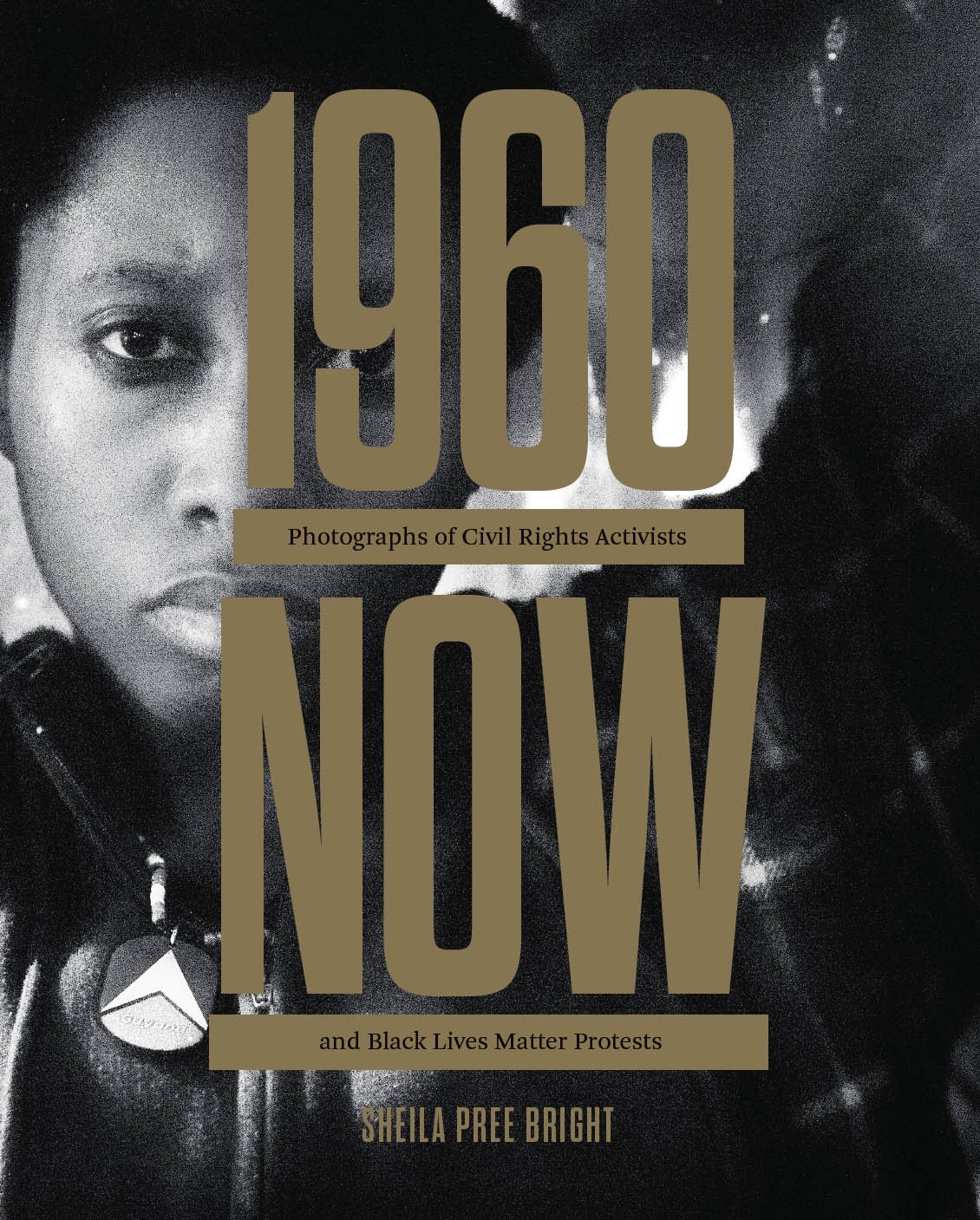

Title: #1960now : photographs of civil rights activists and black lives matter protests / by Sheila Pree Bright.

Other titles: Hashtag1960now | Hashtag 1960 now

Description: San Francisco, California : Chronicle Books, 2018.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018000975 | ISBN 9781452170725 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Black lives matter movementPictorial works. | Civil rights movementsUnited StatesPictorial works. | African AmericansCivil rightsHistorySources. | Documentary photography.

Classification: LCC E185.61 .B85 2018 | DDC 323.1196/073dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018000975

Design by Brooke Johnson and Spencer Vandergrift

Chronicle books and gifts are available at special quantity discounts to corporations, professional associations, literacy programs, and other organizations. For details and discount information, please contact our premiums department at or at 1-800-759-0190.

Chronicle Books LLC

680 Second Street

San Francisco, California 94107

www.chroniclebooks.com

Special Thanks: AJ Favors of Modern Matter; Anne Dennigton of Flux; Michael Simanga, Ph.D.; Nato Thompson; Siri Engberg, Professor; Bridget R. Cooks, Ph.D.; Annette Cone-Skelton of Museum of Contemporary Art Georgia; Likisha Griffin; Deborah Willis, Ph.D.; Aaron Bryant, Ph.D.; Alicia Garza; Eric Luden; Keith Miller; Alesia Graves; Terrell Clark; the Freedom Fighters of now and then; the families of the victims of police brutality; and my husband, Jeryl Bright.

This book is dedicated to the King and Queen, my mother and father, who have nurtured me with their love.

CONTENTS

By Alicia Garza, Cocreator, Black Lives Matter Global Network

By Sheila Pree Bright, Photographer

By Deborah Willis, Ph.D., Chair of the Department of Photography & Imaging at the Tisch School of the Arts at New York University

By Kiche Griffin, Creative Consultant

By Aaron Bryant, Curator of Photography, Visual Culture, and Contemporary Political History at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

By Keith Miller, Curator of the Gallatin Galleries at New York University

INTRODUCTION

THERE ARE MOMENTS THAT CHANGE THE COURSE OF HISTORY FOREVER.

The 1960s are widely recognized as a tumultuous, painful, and inspiring period in the history of the United States, where significant social upheaval occurred as a result of Black people waging a catalytic fight over civil rights. During the height of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, America was challenged to live up to its promise of liberty and justice for all.

Of course, like most movements, history is often distorted, bent to accommodate the interests of the powerful. The events of the 1960s are not exempt from such revisions, silencing the voices and the contributions of many who helped to shape the period and the popular consciousness. The Civil Rights Movement was not one period in history, but in fact, several periods, and the upheaval that occurred in the 1960s was catalyzed by the twenty-year period which preceded it. From sharecroppers in Alabama and throughout the South who organized in the 1930s and 1940s, to the Harlem Renaissance that awakened the imagination of thousands and gave contours to the conditions of Black people from the plantation to the city, the struggle for justice, freedom, and equity has been in motion ever since enslaved Africans set foot on the shores of what was to become America.

Similarly, the Civil Rights Movement was not merely a collection of heterosexual male religious leaders leading their congregations toward freedom. In fact, the Civil Rights Movement was advanced in large part by Black women and queer people who were strategists, community organizers, and visionaries.

Popular narratives of this period in history depicted key figures like Rosa Parks, who led the catalytic Montgomery bus boycott in 195556, as a woman who was too tired after a long day of work to move to the back of the bus, and the boycotts as spontaneous action that occurred in response to the mistreatment of Parks, rather than as a strategic economic intervention in the pattern and practice of segregation.

Lunch counter sit-ins and voter registration drives in the South were seen as having been designed and implemented by well-known figures such as Medgar Evers and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., when in fact, many of those direct actions and strategic interventions in the long legacy of racism and racial terror were designed and implemented by people like Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker and Diane Nash.

The Black Panther Party became known as a movement of Black men with guns, rather than as a political party determined to intervene in the deplorable conditions facing Black communities more than one hundred years after the supposed emancipation of Black people from slavery, led by powerful and visionary women such as Elaine Brown, who became the first woman to chair the party in the decade following the 1960s; Angela Davis, who was jailed and targeted by the FBI for her affiliation with the party, and hundreds of others who set up community service programs and infrastructure for Black people to be able to live with some semblance of dignity.

BY ALICIA GARZA

Cocreator, Black Lives Matter Global Network

In the 1960s, there was no social media to help us counter such depictions of how movements develop, evolve, and impact the political, economic, and social workings of a place. What we do have, however, are pieces of documentation that portray history as it actually happened. Photographs of the events of the 1960s, alongside narratives from those who were involved from different positions and perspectives, are what help us understand the complexity of movements themselves, and rescue said movements from the revisions that allow America to remain firmly locked in its own contradictions.

The movements of now are at the same time impacted by the same dynamics and are challenging those revisions in new and innovative ways. Todays movements are unapologetic about making sure that they themselves write and narrate their own development and progress, and at the same time that they do, challenge others and ourselves to have new problems, rather than rehash the same problems movements have been grappling with forever. The movements of now are faced with the same and worsening challenges that organizers and activists encountered in the 1960ssubstandard conditions in Black communities, a lack of political power, and an amnesia that says that Black suffering is a product of our imagination rather than our lived experiences.

Next page