DIAL BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA/Canada/UK/Ireland/Australia/New Zealand/India/South Africa/China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

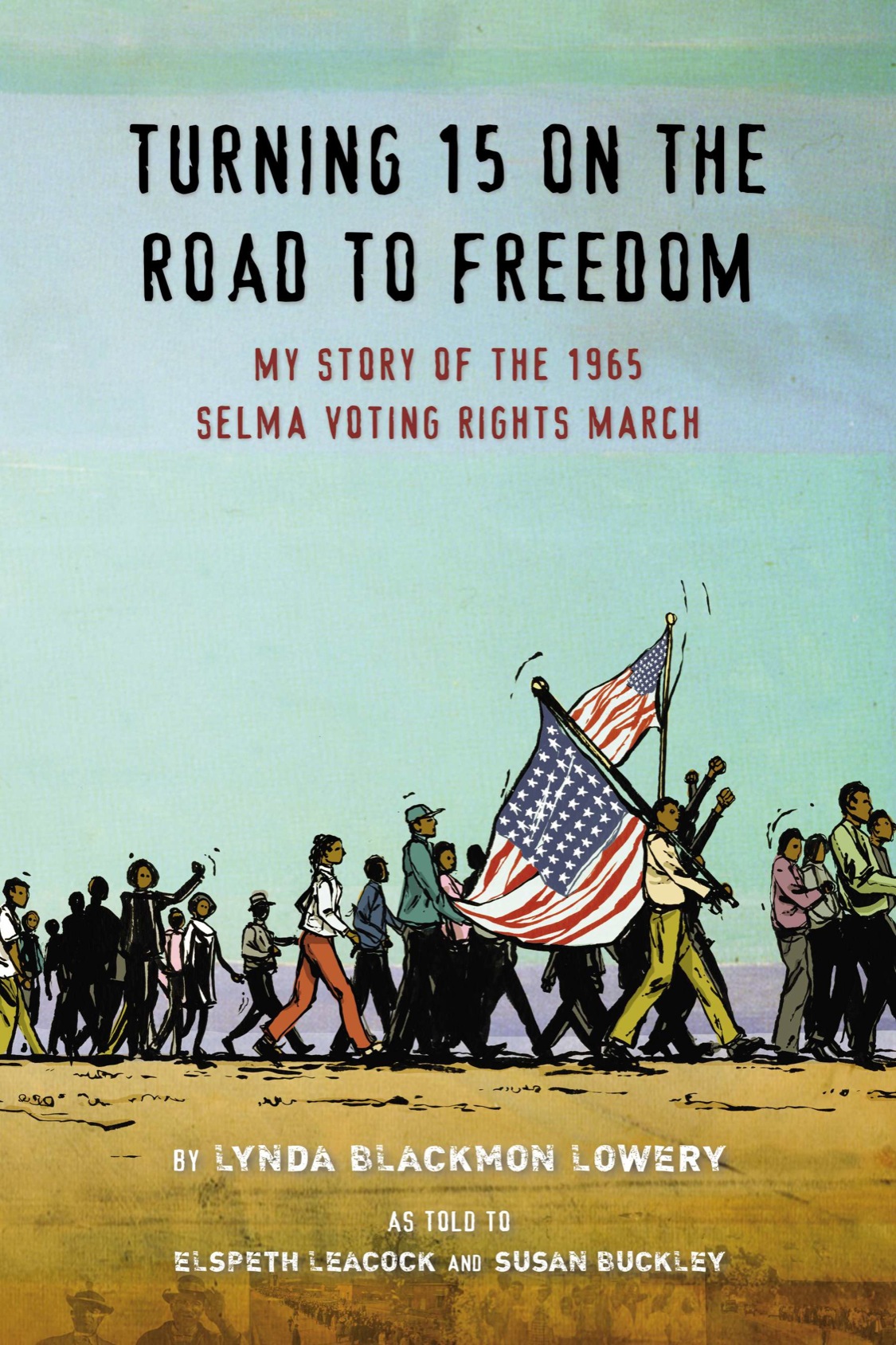

Text copyright 2015 by Lynda Blackmon Lowery, Elspeth Leacock, and Susan Buckley

Illustrations copyright 2015 by PJ Loughran

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

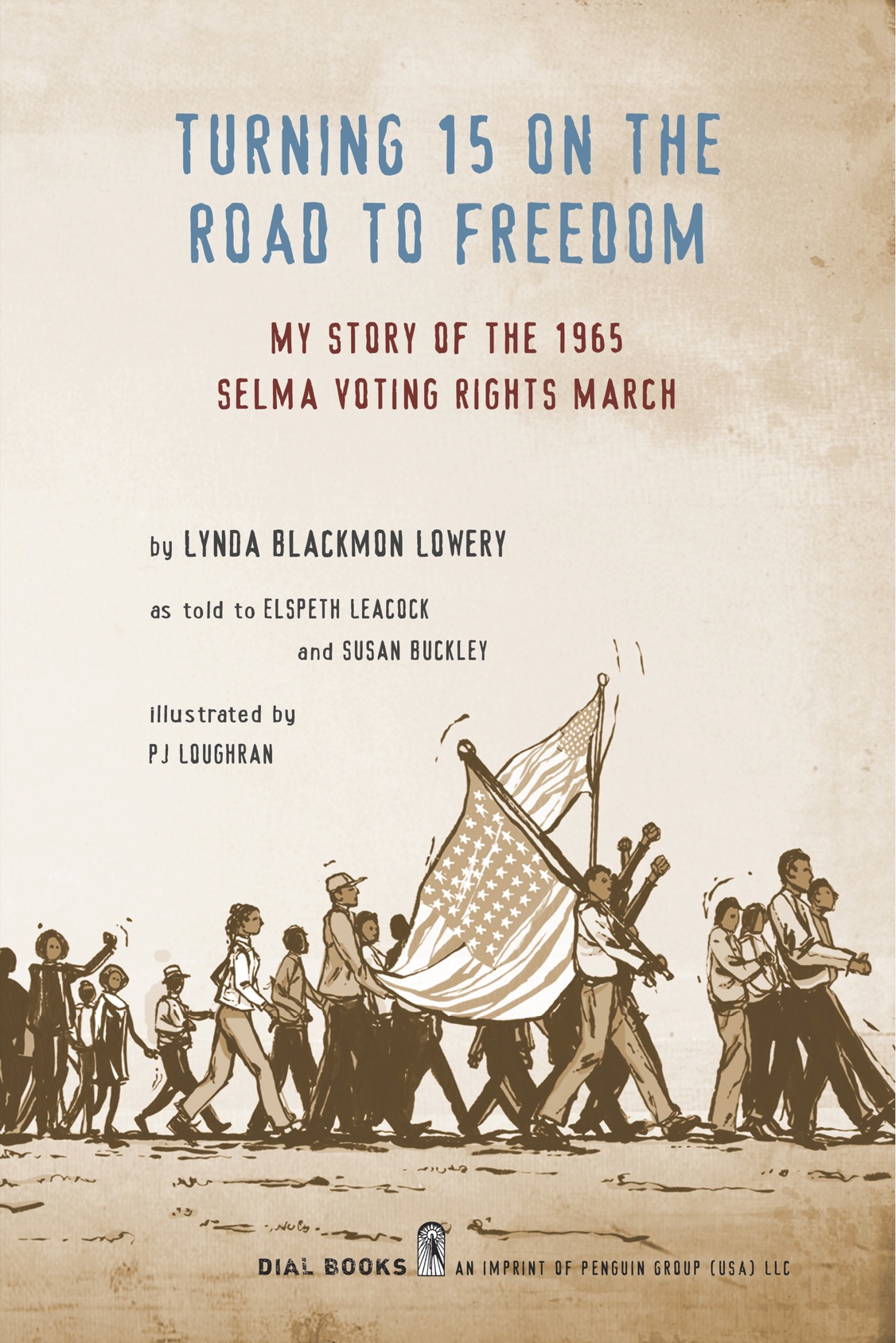

Lowery, Lynda Blackmon, date.

Turning 15 on the road to freedom : my story of the 1965 Selma Voting Rights March /

by Lynda Blackmon Lowery ; as told to Elspeth Leacock and Susan Buckley ;

illustrated by PJ Loughran. pages cm

ISBN 978-0-698-15133-8

1. Selma to Montgomery Rights March (1965 : Selma, Ala.)Juvenile literature.

2. Selma (Ala.)Race relationsJuvenile literature. 3. African AmericansCivil rights

AlabamaSelmaHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. 4. African AmericansSuffrageAlabamaSelmaHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. 5. Civil rights movementsAlabamaSelmaHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. 6. Lowery, Lynda Blackmon, date. I. Leacock, Elspeth. II. Buckley, Susan Washburn. III. Loughran, PJ, illustrator. IV. Title. V. Title: Turning fifteen on the road to freedom.

F334.S4L69 2015 323.1196'073076145dc 3 2013047316

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any

responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Version_1

For Joanne Blackmon Bland,

who brought us together,

and for the children who march for

freedom around the world

Woke up this morning with my mind

Stayed on freedom

Woke up this morning with my mind

Stayed on freedom

Woke up this morning with my mind

Stayed on freedom

Hallelu, Hallelu, Hallelujah.

Im walking and talking with my mind

Stayed on freedom

Im walking and talking with my mind

Stayed on freedom

Im walking and talking with my mind

Stayed on freedom

Hallelu, Hallelu, Hallelujah.

Aint nothing wrong with my mind

Stayed on freedom

Oh, there aint nothing wrong

with keeping my mind

Stayed on freedom

There aint nothing wrong

with keeping your mind

Stayed on freedom

Hallelu, Hallelu, Hallelujah.

Im singing and praying with my mind

Stayed on freedom

Yeah, Im singing and praying with my mind

Stayed on freedom

Hallelu, Hallelu, Hallelujah.

B y the time I was fifteen years old, I had been in jail nine times.

I was born in Selma, Alabama, in 1950. In those days, you were born black or you were born white in Selmaand there was a big difference.

Where I lived, everyone was black. I lived in the George Washington Carver Homes. My buddies and I all felt safe there because everyone watched out for one another. If one family couldnt pay the rent, the others got together and had card parties and fish fries to raise the money. Nobody talked about it afterward either, because the next month it might be you who needed help.

We went to black churches and we went to black schools, where we had caring black teachers. I looked forward to going to school.

The Ku Klux Klan stayed away from us. (They were a group of crazy white folks who hated us black people and were determined to keep us out of placesto keep us segregated.)

They drove through other black neighborhoods, hiding their faces with sheets on their heads, yelling racial slurs, blowing their horns, and cursing and shooting their guns. They rode through areas where they knew they could scare people, but they would not ride through the George Washington Carver Homes.

I felt safe and secure.

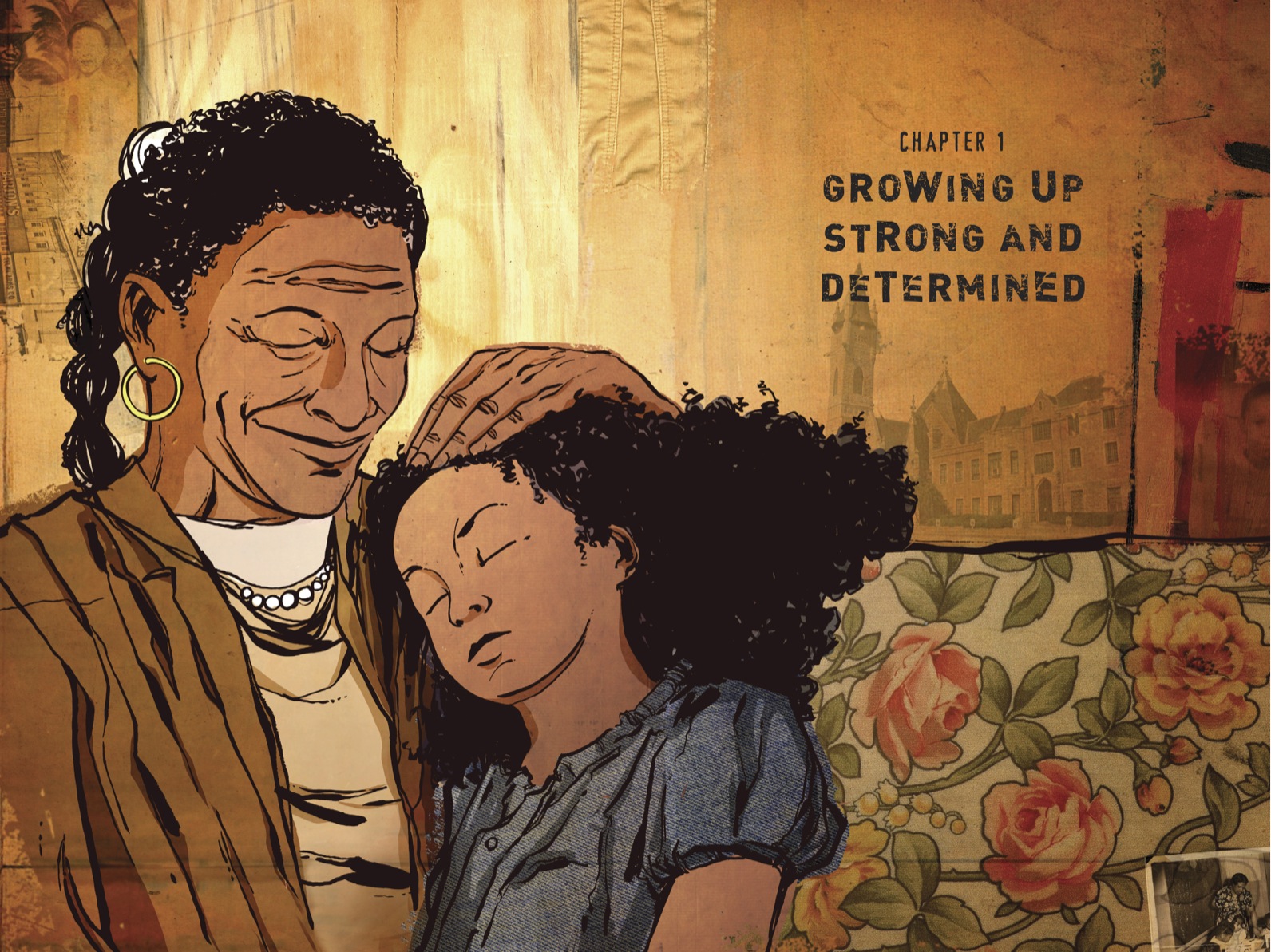

We were poor then, but I never knew it. I cant remember a day in my life when I went hungry, even after my mother died when I was seven years old. My daddy made sure of that. I loved the ground my daddy walked on. I did. When different family members wanted to take us to live with them after Mama died, Daddy said he wasnt separating his kids. He wasnt giving us to anybody. At my mothers funeral, we heard Daddy say that we were his children and he would take care of us. I was the oldest of four. Jackie was next, then Joanne, and then baby Al.

When my mother died, I heard the older people say, If she wasnt colored, she couldve been saved. But the hospital was for whites only. My mother died as a result of her skin color. I just believe that. So segregation hurt my family. It did. It hurt me.

After my mothers funeral my grandmother moved in. She was one determined woman, and she was going to raise us up to be strong and determined too. I remember her saying as she brushed my hair, There is nothing more precious walking on this earth than you are. You are a child of God. So hold up your head and believe in yourself.

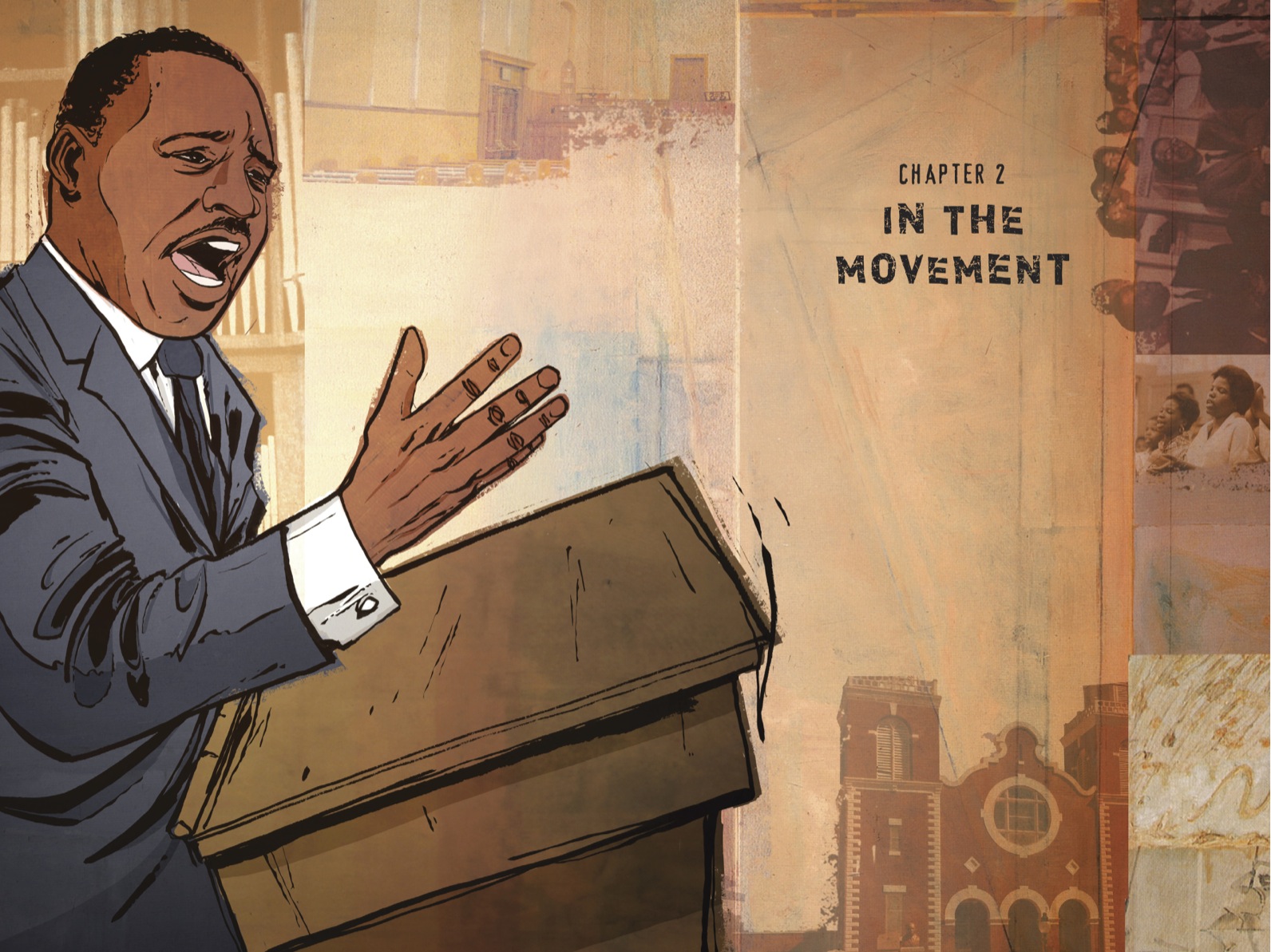

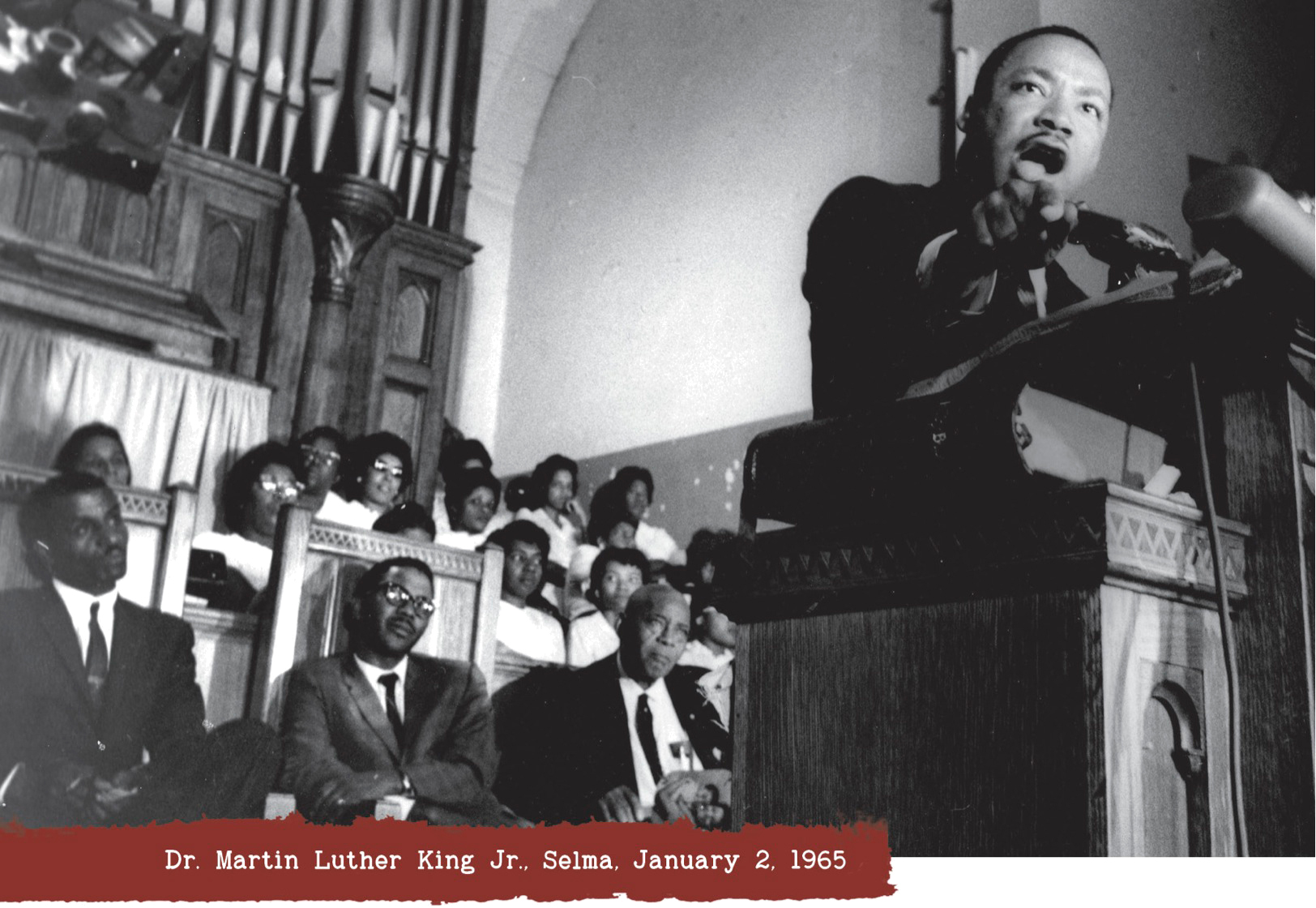

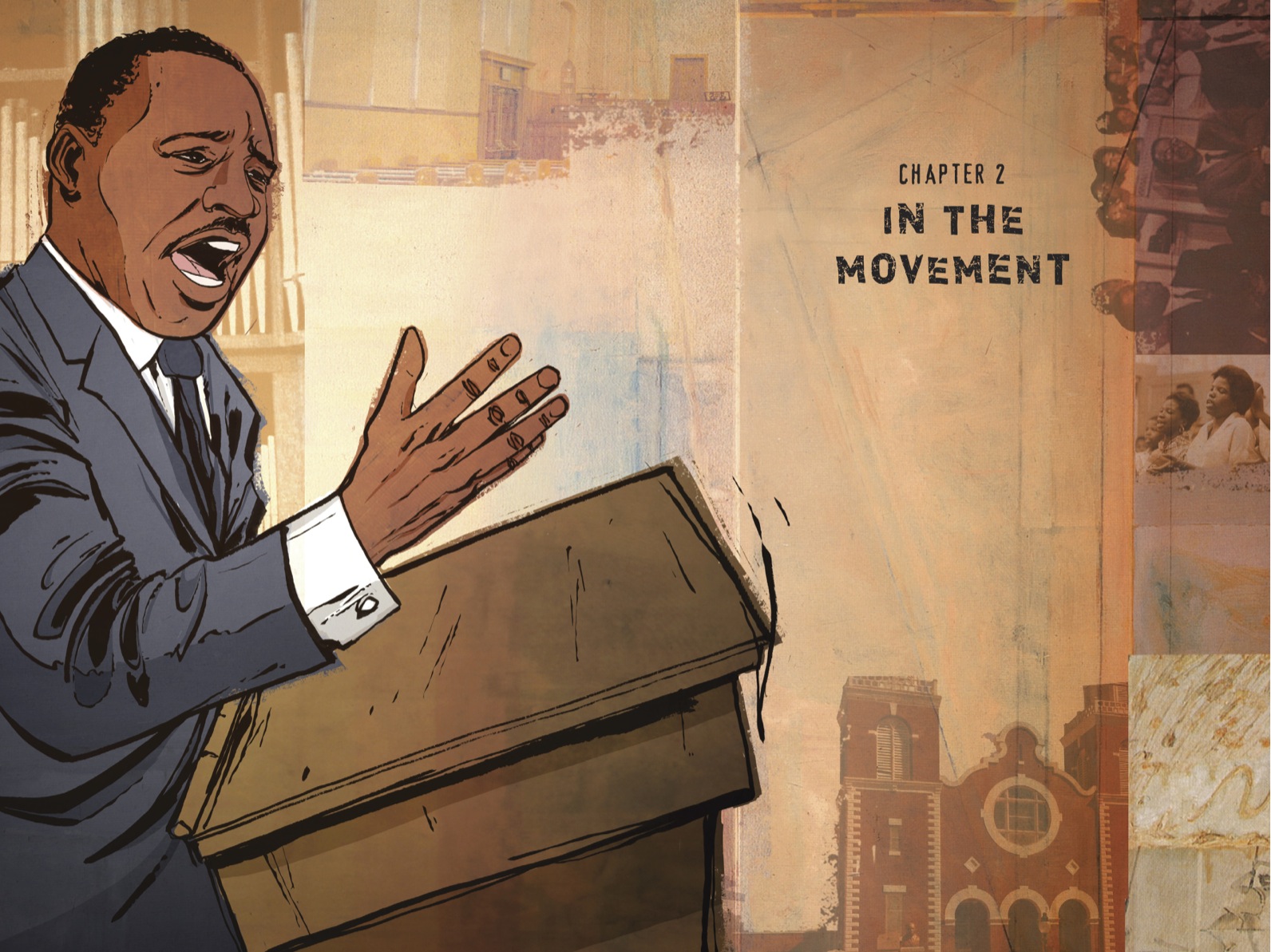

I t was my grandmother who first took me to hear Dr. Kingthats Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. That was back in 1963, when I was just thirteen years old. The church was packed. When Dr. King began to speak, everyone got real quiet. The way he sounded just made you want to do what he was talking about. He was talking about votingthe right to vote and what it would take for our parents to get it. He was talking about nonviolence and how you could persuade people to do things your way with steady, loving confrontation. Ill never forget those wordssteady, loving confrontationand the way he said them. We children didnt really understand what he was talking about, but we wanted to do what he was saying.