Copyright 2016 by Bill Yenne

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper, website, or broadcast.

Regnery History is a trademark of Salem Communications Holding Corporation; Regnery is a registered trademark of Salem Communications Holding Corporation

First e-book edition 2016: ISBN 978-1-62157-554-2

Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file with the Library of Congress

Published in the United States by

Regnery History

An imprint of Regnery Publishing

A Division of Salem Media Group

300 New Jersey Ave NW

Washington, DC 20001

www.RegneryHistory.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Books are available in quantity for promotional or premium use. For information on discounts and terms, please visit our website: www.Regnery.com .

Distributed to the trade by

Perseus Distribution

250 West 57th Street

New York, NY 10107

CONTENTS

Any time war breaks out between Japan and the United States, I shall not be content merely to capture Guam and the Philippines and occupy Hawaii and San Francisco. I am looking forward to dictating peace to the United States in the White House in Washington, DC.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander in Chief, Imperial Japanese Navy Combined Fleet, (January 24, 1941, as released by the Domei news agency on December 17, 1941)

The [Japanese] could have landed anywhere on the coast, and after our handful of ammunition was gone, they could have shot us like pigs in a pen.

Major General Joseph Warren Stilwell, Commander, Western Defense Command Southern Sector, (December 11, 1941)

The contention that the United States cannot be invaded is as much a myth as that the Maginot Line could not be taken, or that Pearl Harbor or Singapore are impregnable... it will be for us to say when, where and how we will strike.

The Japan Times , in an item broadcast over short wave, (January 9, 1942)

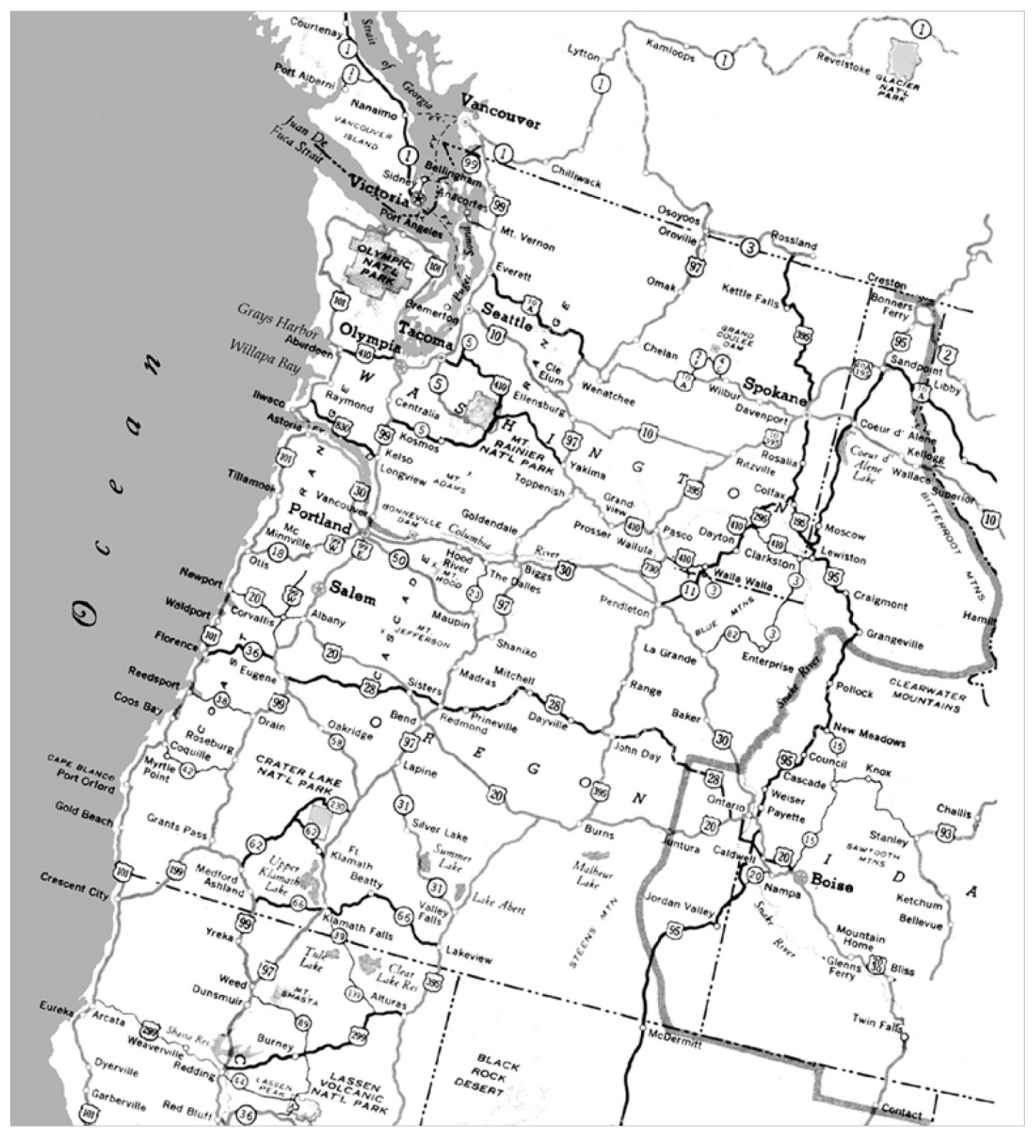

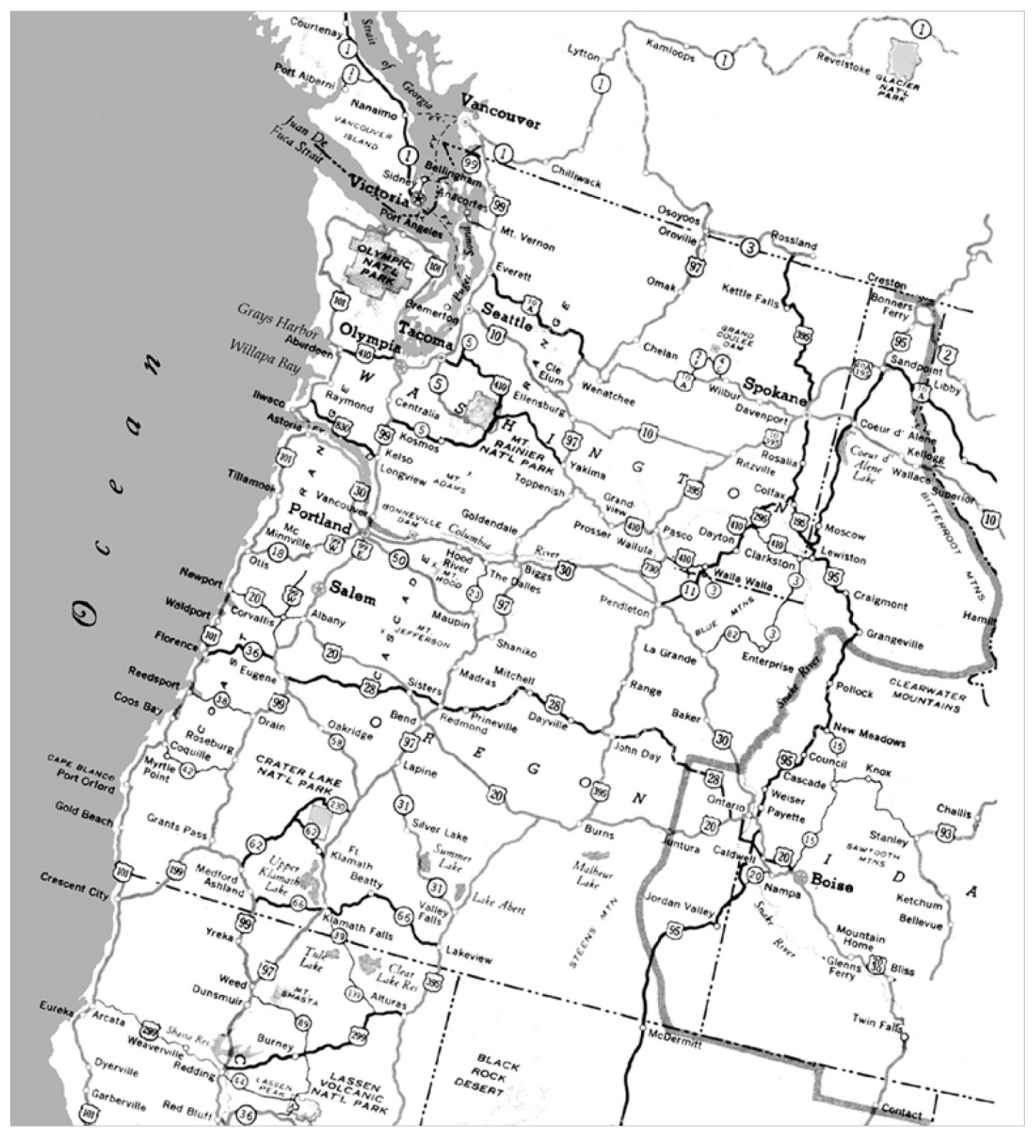

The Pacific Northwest and its Highway Grid (1941) Library of Congress

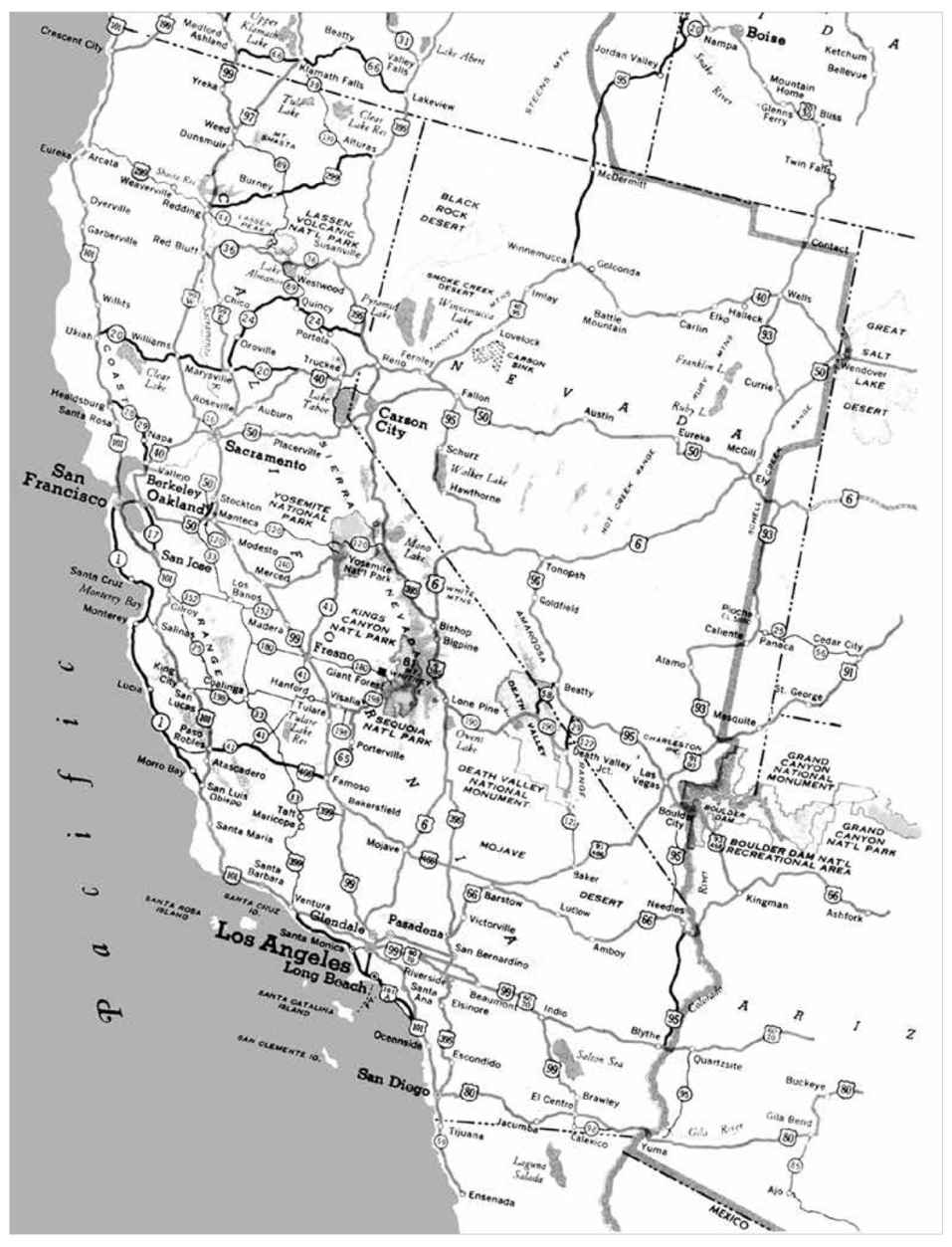

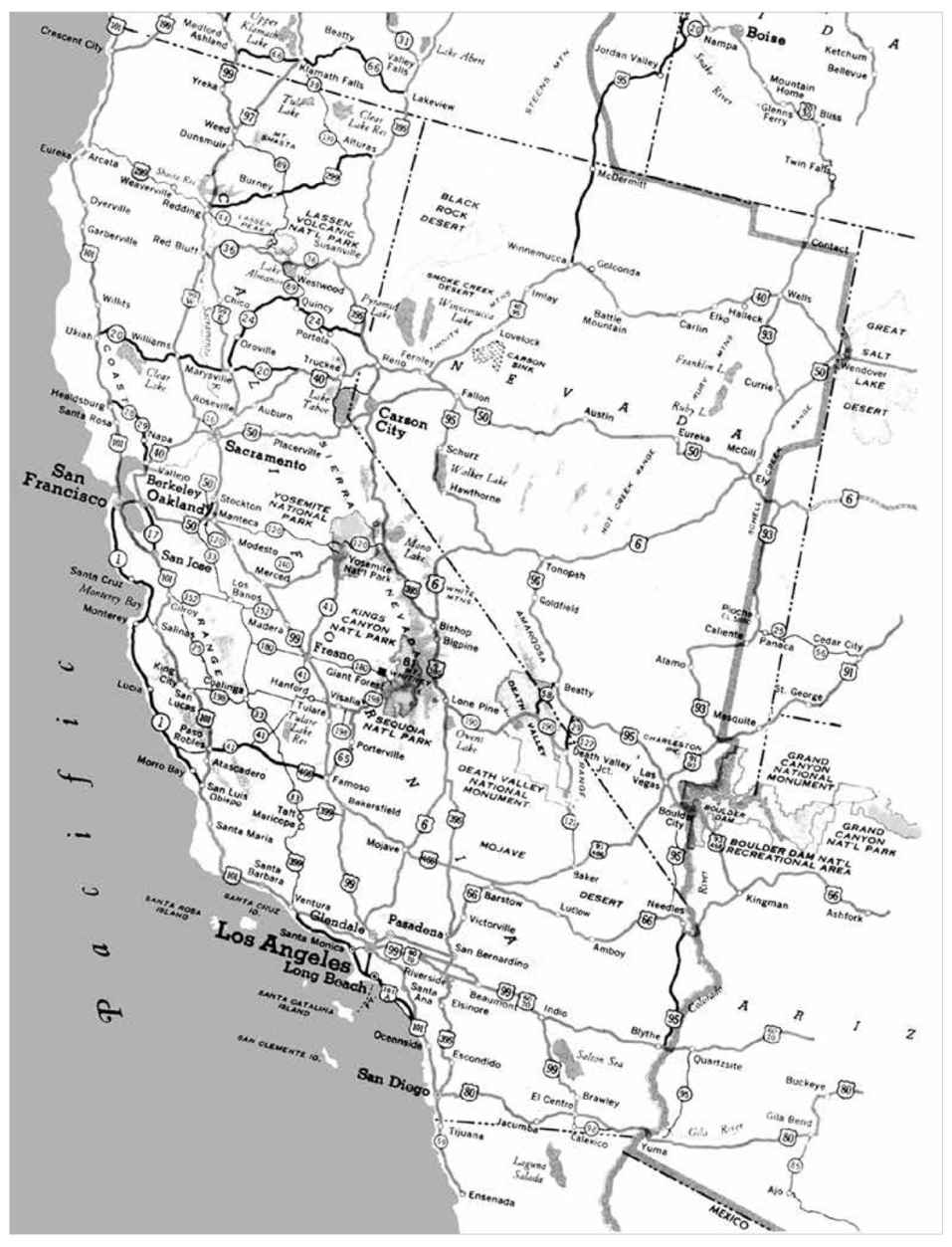

California and Nevada and their Highway Grid (1941) Library of Congress

B rigadier General Henry Harley Hap Arnold, the future commanding general of the U.S. Army Air Forces (the precursor of the U.S. Air Force) in World War II, was on the front lines of the potential Pacific War before such a thing could have been imagined by most. As the commander of the 1st Wing at March Field, California, he well knew and understood the potential threat faced by the people of the Pacific Coast. His concerns were summarized in comments published in the Los Angeles Times , on January 12, 1936:

Forty high-speed bombers, launched from a carrier off this coast, could in a few minutes completely demoralize the Los Angeles area by the simple expedient of bombing the exposed siphons or the Los Angeles Aqueduct in Owens Valley.... In so doing these enemy planes need not even approach the air defenses of Los Angeles, yet the havoc created by such a well-directed attack would be far more effective than if they dropped their bombs on the very heart of the city. Some 2 million people are absolutely dependent on Los Angeles water supply, he wrote, and a one-minute rain of bombs could force the evacuation of Los Angeles and make the area as arid as it was when Cabrillo first sighted this coast [in 1542].

In 1936, the thought that such a thing would happen, or indeed that it even could happen, was considered a far-fetched fantasy. But then, there were a lot of things which were about to happen, or almost happen, during World War II, which seemed beforehand as unimaginable. Prior to the spring of 1940, for instance, the thought of a German conquest of virtually all of non-fascist Western Europe in a little more than a month and a half was seen as impossiblea ridiculous proposition. Then suddenly, the specter came to life. The rapid, decisive defeat of France, one of the worlds preeminent powers, numbed the world. In the summer of 1940, a German invasion of the United Kingdom, untouched by cross-Channel invaders since 1066, seemed inevitable.

Fear and bleak gloominess fell upon that land and her people, who knew how little they could throw up against the blitzkrieging legions of Nazi Germany if they made it ashore. The people of southern England scanned the English Channel horizon with worried eyes. The people held their breath and did what they could with what they had to prepare.

A great deal has been written about the German invasion of Britain in 1940 that never came. Operation Sea Lion, and the efforts to defend against it, remain an indelible part of the historical memory of Britains wartime era.

It set a somber precedent that was revisited by the people of the West Coast of the United States a year and a half later. Worried, they looked westward toward the vastness of the Pacific, squinting at the horizon for signs of a Japanese invasion armada.

From December 1941 and well into 1942, the same fear and the same bleak gloominess felt in England fell upon the Pacific Coast and its people who knew how unprepared they were to fight the Imperial Japanese Navythe same force that had just reached thousands of miles across the ocean to cripple the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor in a few hoursand the Imperial Japanese Army, which was conquering large swaths of Southeast Asia and humbling proud European colonial powers.

Neither invasion ever came, and there are many who insist that neither ever could have come, but, in those fearful times, youd have made no headway trying to persuade someone in Dover or Hastings in 1940, or to someone in Santa Barbara, California, or Astoria, Oregon, in 1941 to be less fearful. The sky seemed to be falling, and there was no way to stop the enemy. Fearful Americans looked out to a once peaceful ocean where Japanese submarines now roamed, torpedoing freighters and shelling the shoreline. Paranoia descended upon the land. Rumors ran rampant, and a cold dread gripped those who were charged with protecting a no longer peaceful Pacific Coast and the people they were charged with protecting.

D ecember 7, 1941, arrived as a quiet Sunday morning on the West Coast. It didnt stay that way for long. In the early afternoon, in Washington, D.C., Secretary of the Navy Frank Knox told President Franklin Roosevelt that a message from Hawaii had reached the Mare Island Naval Shipyard north of San Francisco. It read: Air Raid Pearl Harbor. This is no drill. The message had arrived at 10:58 a.m. California time, 7:58 a.m. Hawaii time.

Knox told Roosevelt that the attack was in progress even as they spoke.