First published in Great Britain 2000 by

Leo Cooper

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright 2000 by Cyril Cunningham

ISBN 0 85052 767 8

The right of Cyril Cunningham to be identified as the author of this

work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright,

Design and Patents Act of 1993

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Typeset in 10/13pt Sabon by

Phoenix Typesetting, Ilkley, West Yorkshire

Printed in England by Redwood Books, Trowbridge, Wiltshire

BY

M. R. D. FOOT

All things change; even what the old officer class used to regard as something as fixed as the laws of the Medes and Persians, how one ought to behave if one had the bad luck to become a prisoner of war. One gave ones name, ones rank, ones number and no other information of any kind; ones duty was to escape and, failing a successful escape, one did ones best to make life awkward for the enemy.

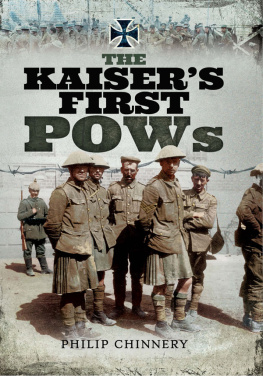

Since the end of the wars against Hitler and Hirohito, things have not looked quite the same. In this book Cyril Cunningham explains, from inside knowledge, how badly the old rules applied as soon as five years later, during the war in Korea. Escape there was made much more difficult for British or American fighting men as it had been in the war against Hirohitos Japan by the brute fact that they looked entirely unlike the local inhabitants through whose villages they might have to pass. Escapers stuck out like sore thumbs. Besides, they could not look for that help from passing strangers which had saved so many hundreds of escapers and evaders in Nazi-occupied Europe; in communist-dominated North Korea the party and its police ruled with an iron grip. No one, it seems, managed a complete get-away, though several got out of their unspeakable camps for some days on end, only to be beaten up on recapture.

Moreover, within the camps, sticking to name, rank and number only made trouble. The North Koreans, when they bothered to keep any prisoners alive (they shot a great many sooner than bother to feed and shelter them) did not handle them gently; most were consigned to caves and death from starvation and neglect, or to slave labour gangs that were worked to death.

The Chinese took a gentler line with their prisoners, but were much more thorough. Every single man received a prolonged, personal cross-questioning, often preceded by filling in a long form; nobody found it feasible even to try to stick to name, rank and number. Chinese initial ignorance of the ways of the west led to some Royal Marines (the first British military p.o.w. they captured) to be taken to task and beaten for their impertinence when they claimed to own motor cycles or motor cars, and yet not a single pig or chicken; a barbarity they soon discovered and not repeated later. None of the prisoners had received any preparatory warning about how much it would, and how much it would not, be safe to vouchsafe to an enemy: an important lacuna in training in how to behave after capture, which has presumably by now long been remedied. Many prisoners had the common sense to keep to themselves what they knew about their fellow prisoners, but they were at the mercy of others who for political or selfish reasons sought to curry favour with their captors by splitting on their comrades in arms.

A surprisingly high proportion of the captured Royal Marines seemed ready to embrace the communist social system and its propaganda, but very few of them were still inclined to the left after repatriation. They received a frosty reception when they called at the CPGB headquarters in King Street and were disillusioned by the poor calibre of the party members they made contact with in their home towns.

It has for years been taken for granted by the news media that the intensely political treatment the prisoners received in captivity led to their having been brainwashed; a myth Mr. Cunningham is at pains to dispel, hardly before time. It is a relief to get the truth established; he leaves room for little doubt.

Mr Cunningham wields a clear pen as well as an informed mind. He is much more interested in the political realities of these mens experiences than in cataloguing their physical sufferings, and explains neatly how they fitted into the cold war propaganda that was being ladled out by the Chinese and North Korean governments as well as by the Russians. Elderly readers will recall, for instance, the allegations that the Americans had used germ warfare in Korea; wholly unsubstantiated in fact yet supported by the confessions of captured American aircrew who had been psychologically harried and physically abused until they agreed to sign.

Studies of human kind under pressure are always interesting; this is a most readable addition to the already extensive literature that bears on this tense and difficult subject.

In this book I have attempted to give a straightforward and integrated account of the treatment of British prisoners of war by the Chinese Communists and the North Koreans during the war with the United Nations Forces in Korea (June 1950July 1953). Although several books have been published by former p.o.w., these were essentially the personal experiences of a select minority. Nothing has been published by former p.o.w. who collaborated with their captors. The Ministry of Defence Blue Book (actually a pamphlet of 41 pages) on The Treatment of British Prisoners of War in Korea, which I had a hand in preparing, was published in 1955 but gives no insight into their side of the story. It received a hostile reception from the British press which accused the Government of suppressing information about the behaviour of British officers in captivity. This extreme skepticism arose from the fact that the Blue Book implied that all the so-called progressives among the British prisoners were Other Ranks whereas the Americans had admitted that many of their officers as well as enlisted men had co-operated with the enemy. How was it, the angry press demanded, that British officers alone appeared to be immune to Communist blandishments? That question was never answered and to this day nobody has vouched for the authenticity of the facts in the Blue Book.

Clearly, an overall picture of the treatment of all segments of the prisoner population and the events which occurred in each of the twelve camps in which they were incarcerated can only be given by one who was at the centre of prisoner of war intelligence at the material time.

Soon after the outbreak of the Korean War a defunct Prisoner of War Intelligence organization, M.I.9, was reactivated, renamed A.I.9 and placed under the Air Ministry because it was housed in Air Ministry premises. Its purpose was to collect intelligence on prisoners of war and to teach combat units Conduct After Capture, especially survival techniques.