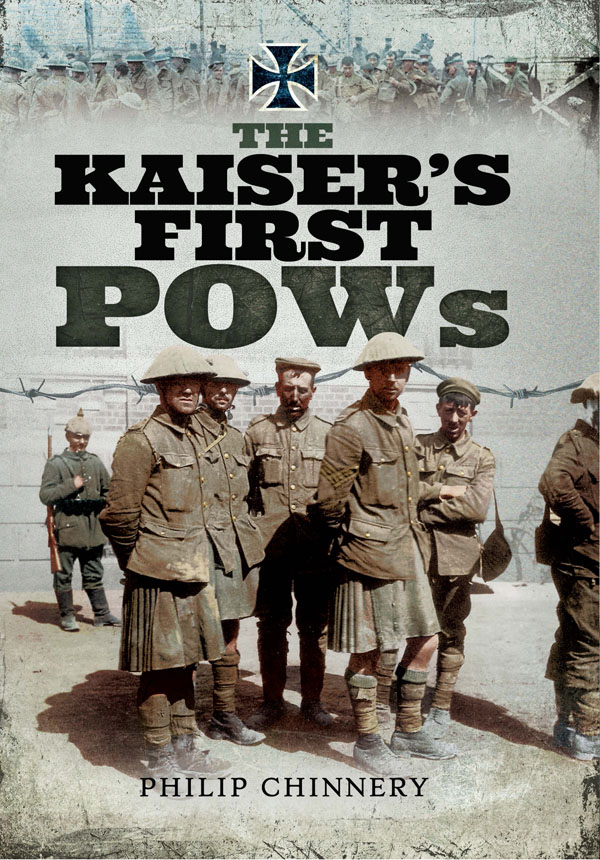

The Kaisers First POWs

The Kaisers First POWs

Philip D. Chinnery

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Pen & Sword Military

An imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Philip Chinnery 2018

ISBN 978 1 47389 228 6

eISBN 978 1 47389 230 9

Mobi ISBN 978 1 47389 229 3

The right of Philip Chinnery to be identified as Author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Pen & Sword Books Limited incorporates the imprints of Atlas, Archaeology, Aviation, Discovery, Family History, Fiction, History, Maritime, Military, Military Classics, Politics, Select, Transport, True Crime, Air World, Frontline Publishing, Leo Cooper, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing, The Praetorian Press, Wharncliffe Local History, Wharncliffe Transport, Wharncliffe True Crime and White Owl.

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Introduction

T he blazing inferno that became the First World War was sparked by an event that took place in Sarajevo on 28 June 1914. On that day Gavrilo Princip, a member of the Black Hand, a Serbian nationalist secret society, assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austria-Hungarian throne. Shortly thereafter Austria-Hungary issued an ultimatum to Serbia, demanding that the assassins be brought to justice. Dissatisfied with the result, Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia on 28 July 1914.

Serbia had Slavic ties to Russia, which began to mobilize its vast army. Germany was allied to Austria-Hungary by treaty and considered the Russian mobilization to be an act of war against Austria-Hungary, so declared war on Russia on 1 August.

France was bound by treaty to support Russia and declared war against Germany and Austria-Hungary on 3 August. On the following day German troops crossed the frontier into neutral Belgium. They were implementing the Schlieffen Plan, created in 1905 by the then German army chief of staff, Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen, which involved an advance into neutral Belgium before swinging south into France. This would avoid the fortifications along the French-German border and should lead to the defeat of France before Russia had time to mobilize her armed forces.

Britain had guaranteed Belgian independence in the Treaty of London 1839 and once that country was invaded by Germany, Britain declared war on 4 August and prepared to send the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) to support the French and Belgian forces now in contact with the German army.

Further afield, Japan, honouring a treaty with Britain, declared war on Germany on 23 August 1914. Italy was a friend of both Germany and Austria-Hungary, but remained neutral until she joined the British and French in May 1915. The United States would remain neutral until 1917 when President Wilson finally declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917.

Fortunately the Schlieffen Plan did not take into account the stiff resistance encountered in Belgium, nor the presence of the BEF, but it did result in the capture of tens of thousands of Belgian, French and British troops. Before the French could be subdued, Russia joined the war and the Germans found themselves fighting on two fronts. They were more than a match for the Russians, however, and great numbers of Russian prisoners would be taken at the Battle of Tannenberg in East Prussia. The Russians would become the largest single group of prisoners in the German prisoner of war system.

In September 1915 large numbers of Serbian prisoners began to arrive, following the Austro-German-Bulgarian invasion of that country. The Romanian government declared war on the Central Powers in August 1916, leading to the occupation of that kingdom and an influx of Romanian prisoners into Germany. (The countries referred to as the Central Powers were Austria, Hungary, Germany, Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire.)

Captured Russian prisoners about to be marched away to a prison camp.

Italy had joined the war on the side of the Entente Cordiale, the alliance between France, Great Britain and Russia. They were soon under attack from Austro-Hungarian forces and when the Italian front collapsed as a result of the Battle of Caporetto in October to November 1917, large numbers of Italian prisoners began to appear in the German Empire. By the end of the war, the Germans had taken approximately 2.8 million prisoners of war. This book will describe the life and times of these prisoners and the manner in which the Germans dealt with the problems involved in accommodating them.

In 1915 the German government published a book in Berlin entitled 1915 . It was produced in an attempt to portray the Germans as a civilized people who were destined to win the war, but in the meantime they would treat their prisoners with care and compassion. The aim of this book is to compare 1915 to the reality of captivity, as experienced by the prisoners themselves. The book was translated into English by the German publisher and sections are reproduced here, word for word, with errors of spelling and grammar included to add to the authenticity. Personal accounts from former prisoners will describe the reality of falling into the hands of the German army and life as a prisoner of the Kaiser.

Philip D. Chinnery, London 2016

Chapter 1

The Horrors of War

A lthough the German invasion of neutral Belgium horrified the world, it was an important part of the Schlieffen Plan, designed to avoid the French fortifications along the French-German border. The Germans were confident that they could defeat the French quickly, but the Belgian army put up a stiff resistance, slowing the German advance and allowing the British Expeditionary Force to join the fight. As the British Tommies embarked for the continent, the mighty British Empire began to stir and Canadians, Australians and Indians also began to prepare to join the war.

Although Britain did not maintain a large standing army like France and Germany, it was highly professional as the Germans discovered to their cost when they first met the 80,000-strong BEF at Mons, a small Belgian town, on 23 August 1914. The BEF formed up on the left flank of the French army and although outnumbered by about three to one, they managed to withstand the advance of the German First Army for forty-eight hours. They prevented the Germans from outflanking the French army, but when the Frenchmen began to retreat, the British had little alternative but to fall back too. British casualties were recorded at just over 1,600 but they had inflicted three times as many casualties on the Germans.

The two corps of the BEF retreated for two more days until the II Corps commander, General Horace Smith-Dorrien decided to stop and fight. Although he was disobeying the orders of General Sir John French, the BEF commander, his men were exhausted and in low spirits. On the morning of 26 August they reached Le Cateau and began to dig in. They were at a disadvantage from the start due to lack of cover on the open ground, with the Germans advancing from the higher ground to the north. The men and artillery of the BEF were badly exposed and the heavy German guns caused significant losses among the defenders. By the time the battle was over, 7,812 men had been lost and thousands more were captured. Although the German advance had been halted for a while, General French was livid that Smith-Dorrien had disobeyed his orders and he was eventually relieved of his position on health grounds.